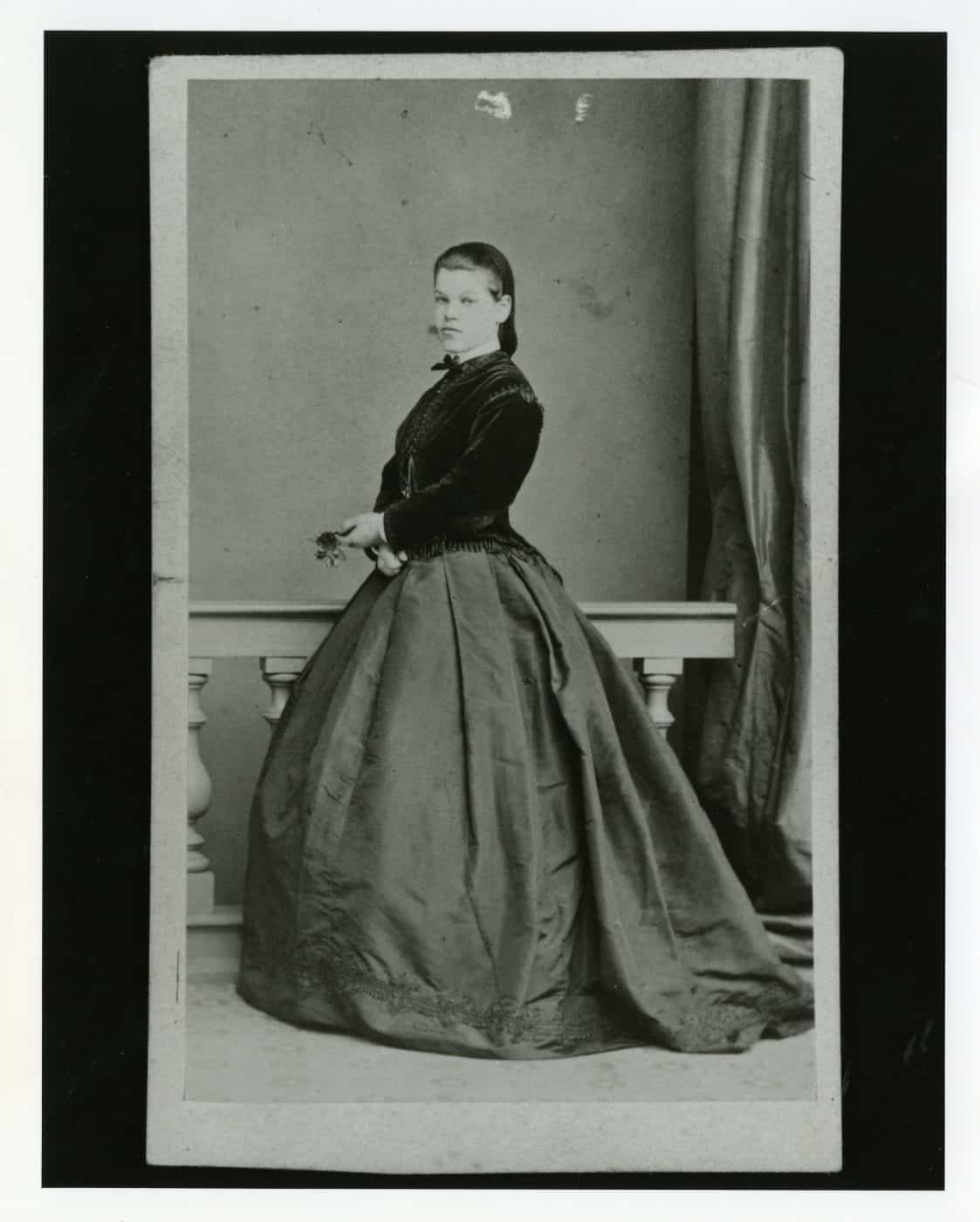

July 17, 2022The cranky, know-it-all spinster is a stock figure in the stories of many families — including the Rothschilds. Among members of the English branch of that famous international banking family, Alice de Rothschild (1847–1922) has long been cast in that role.

For decades, any mention of “Miss Alice,” however affectionate, came with a roll of the eyes. Famously persnickety, she had firm ideas about how things should be done — and she did not keep them to herself. According to family legend, when King Edward VII paid her a visit, she asked him to remove his hands from her silk upholstery.

Happily, the new exhibition “Alice’s Wonderlands” replaces the caricature of Miss Alice with a finely observed portrait that shows us who she really was, what she achieved and why that matters. Housed at Waddesdon Manor, the grand Rothschild estate turned house museum, 90 minutes from London — the very place where she scolded the king — the show is as delightful as it is enlightening.

With the help of rare early color photographs, along with Alice’s prized lyrical pastel drawings, Renaissance and 18th-century paintings, Sèvres porcelain and Savonnerie carpets — including one commissioned by Louis XIV for the Louvre’s Long Gallery — the exhibition reveals a woman who is imaginative and intelligent, confident and canny.

She was fearless, too. In her time, it was a given that only a man could run a large estate. Well, she owned and managed three — and simultaneously, too.

Indeed, estate management came to be her métier. As I walked through the show’s rooms recently, I realized that Alice de Rothschild had a genius for it. Evidence can be found in everything from her notes about how to protect delicate fabrics from light damage to her avant-garde adoption of a particular type of tiered garden beds to her gift for hiring and then training staff.

The exhibition’s whirlwind tour of the three wonderlands introduces us to the imposing, Frenchified faux château Waddesdon Manor and the pink English fairyland pavilion at Eythrope, just next door, which together encompass 5,000 acres. We also take a trip to Grasse, France, where Villa Victoria stood on a mere 350 acres of mountainside, a Tyrolean homage to the Austrian branch of the Rothschilds into which she was born.

Today, Villa Victoria no longer exists, and Eythrope’s pavilion has been significantly altered. But Waddesdon survives much as it was, and it is open to the public. The setting and subject of “Alice’s Wonderlands” thus feel like a perfect fit — even if the manor is the only one of the three wonderlands that Alice did not create entirely herself.

Her brother Ferdinand (1839–98) completed the house in 1883, but she was in charge from the start. (Tragically, in 1866, Ferdinand’s wife, Evelina, died during childbirth, as did their just-born child. He never remarried.) Ferdinand left Waddesdon’s management to his sister because he knew that she would look after it better than anyone else. And indeed she did. As Mia Jackson, the manor’s curator of decorative arts and curator of the show, observes, without Alice “Waddesdon would not have survived.”

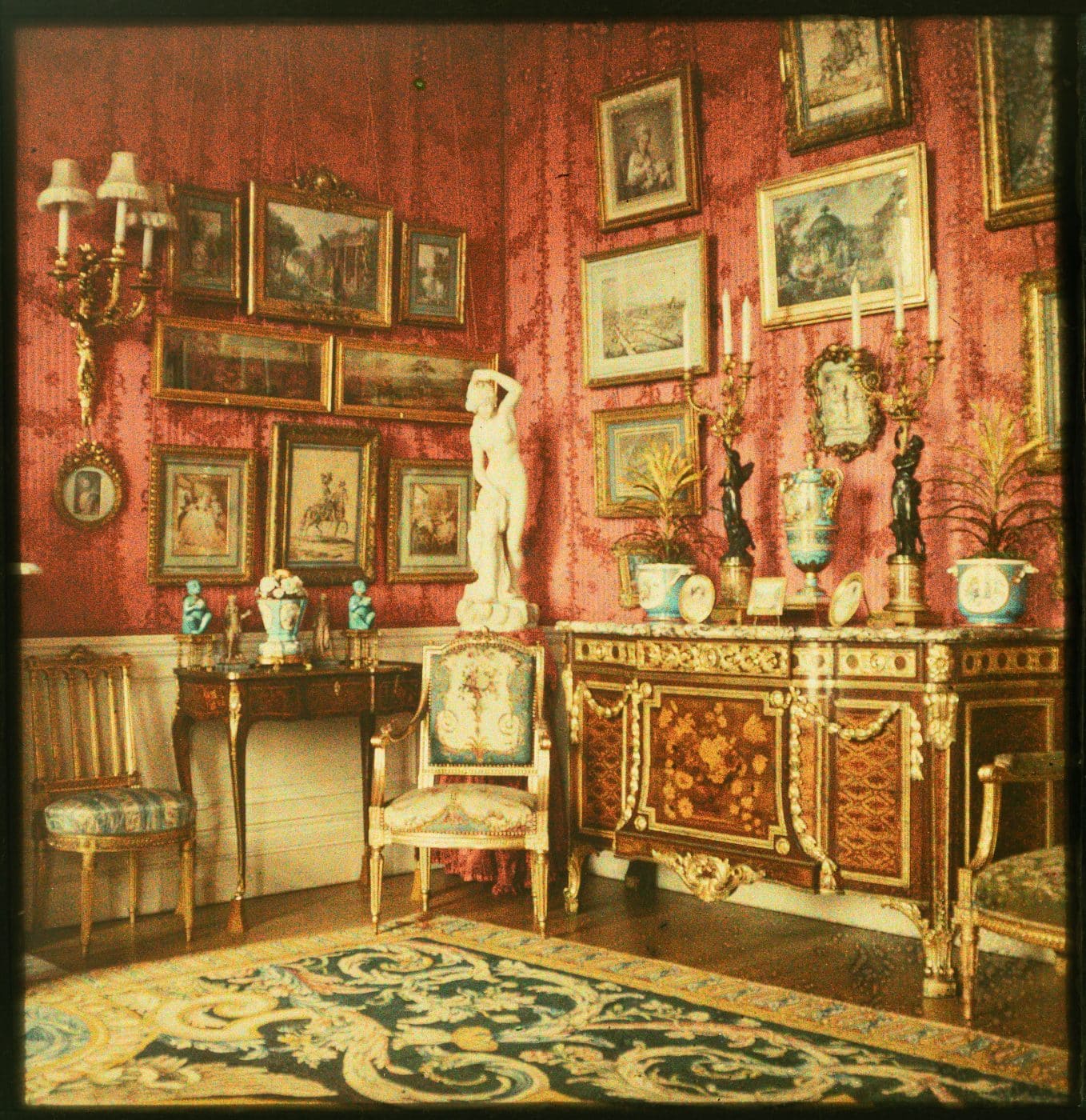

Conceived by Ferdinand and realized by the fashionable French architect Hippolyte Destailleur, the wildly and marvelously improbable Waddesdon looks like a turreted French Renaissance castle that woke up one morning to find itself set in lush English woodlands. Ferdinand decorated its main floor in the highest 18th-century French style: JEAN HENRI RIESENER FUNITURE, tapestries from Gobelins and Beauvais, Parisian wood paneling for the walls, plus all those pieces of Sèvres porcelain and Savonnerie carpets.

When, after Ferdinand’s death, she became Waddesdon’s owner, Alice kept that floor much as it was. Upstairs, however, necessity and taste led to changes.

She replaced Ferdinand’s sporting paintings, which hung in the long corridor of the Bachelors’ Wing, with an imaginative wall display of her armor holdings — an usual collecting area for a woman then as now.

As chatelaine, Alice also made herself a luxurious sitting room upstairs, which has been re-created for the show using newly discovered color photographs she commissioned around 1910. The images themselves are exhibited, and thanks to her expert attention to preservation, a good many of the room’s contents survive in first-rate condition, not least a Riesener chest of drawers and that carpet commissioned for the Louvre.

Elsewhere in the show, a long corridor from Eythrope has been re-created. Near the top of its longest uninterrupted wall hangs a series of Renaissance portraits. All have curved backs that appear to curl onto the ceiling, enabling the sitters to look down and say hello to us.

Another display from Eythrope conveys Alice’s delight in the eclectic presentation of art. Refined Renaissance majolica hangs next to homely early English earthenware. Each seems enlivened by the company it is keeping.

The exhibition’s Family Room gives visitors a chance to do a little genteel snooping, presenting letters, estate books, personal photos, Miss Alice’s garden book and detailed notes for house staff. Here, we come to truly appreciate how the pursuit of excellence guided all aspects of her choices as an estate manager.

In 1906, she wrote to George Johnson, Waddesdon’s head gardener, to remind him that “[q]uality is the one thing you must study in all your work.” Recognizing quality remains as important now, 100 years after her death, as it was then.

Alice de Rothschild left her English estates to her nephew James, who was from the French branch of the family. His wife, Dorothy, was English, and eventually they settled in her home country. The new owners learned the ropes by watching Alice’s well-trained employees carry out their jobs.

The couple were childless, however, and when James died, in 1957, he left Waddesdon to the National Trust — along with the biggest endowment in the charity’s history to secure its future.

Today, the family connection continues: James’s grandnephew Jacob (now Lord Rothschild) owns Eythrope and brilliantly manages Waddesdon, with the Rothschild Foundation covering much of its running costs.

As the exhibition makes amply clear, Miss Alice was exacting, and we should thank her for her fastidiousness — both because of its role in preserving Waddesdon and because of what it teaches us about the value of high quality and high standards in our own lives.

On my first visit to Waddesdon, some 20 years ago, I learned of a rule of Miss Alice’s that I took to heart. “When handling a fragile object, always use two hands.”

I am happy to report that the survival rate of the wine glasses in my house has indeed improved since then — even if I failed to adopt the rule’s codicil: “Always keep silent when washing them.”