July 25, 2021In the 18th century, European and English royals adored Japanese lacquerware. Marie Antoinette loved it so much she lined an entire room at Versailles with lacquered panels in 1781. In the Art Deco period, French furniture designers partnered with Japanese lacquerers to create a whole new genre of shimmering cabinetry. In recent years, Irish duo Zelouf & Bell have reinterpreted Japanese-style lacquer with designs inspired by vintage floral kimono patterns.

The art of Japanese lacquer, also known as urushi, goes back some 9,000 years. It has ebbed and flowed in popularity but has always had ardent admirers and remains highly sought after. The famous Japanese-decorative-arts connoisseur E. A. Wrangham, whose collections were auctioned off at Bonhams London in what the house describes as a series of “now-legendary” sales, claimed that Japanese lacquer pieces “display the finest taste and most exquisite craftsmanship of all the world’s applied arts.”

Lacquerware appeals in many ways: variety and depth of colors, intricacy of design, restrained elegance and the incredible difficulty of mastering the art. It’s also beloved for its lavish use of gold, silver and inlays. In the ninth century, artisans started sprinkling lacquer with powdered gold and silver in a technique called maki-e. They inlaid it with mother-of-pearl, as well.

Although Chinese lacquer dates to the Neolithic period, which began in 10,000 B.C., long before lacquer made its way to Japan, the Chinese treated the material differently. They used it to create smooth, glossy surfaces, but also for carving, an art that began in the 12th century and is exclusively Chinese. Such pieces are called cinnabar lacquer after the powdered mercury sulfide (cinnabar) employed to produce their characteristic red hue.

Once the art of lacquer was introduced to Japan, the practice took on a life of its own and continued to develop through the modern era. The Japanese focused on surface decoration, expanding the color palette and adding flecks of gold or silver or bits of shell during the application process, when the lacquer was still damp.

Demand for Japanese lacquerware — furniture, trays, writing boxes, screens, incense burners — from the Edo period (1615–1868) and the late-19th century is strong among collectors. “The market always comes back because great antique Japanese lacquerwares are not widely available,” says Jim Marinaccio, of NAGA ANTIQUES, in Hudson, New York, who has been selling Japanese antiques for 51 years to clients in Europe, Korea, the Philippines and the U.S.

“I just had the good fortune to buy back a big collection I put together in the nineteen eighties,” he adds, “including a pair of SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY HIBACHIS in ravishing black and gold lacquer — one with golden willow boughs spilling over an arched bridge, the other of fully flowering trees.”

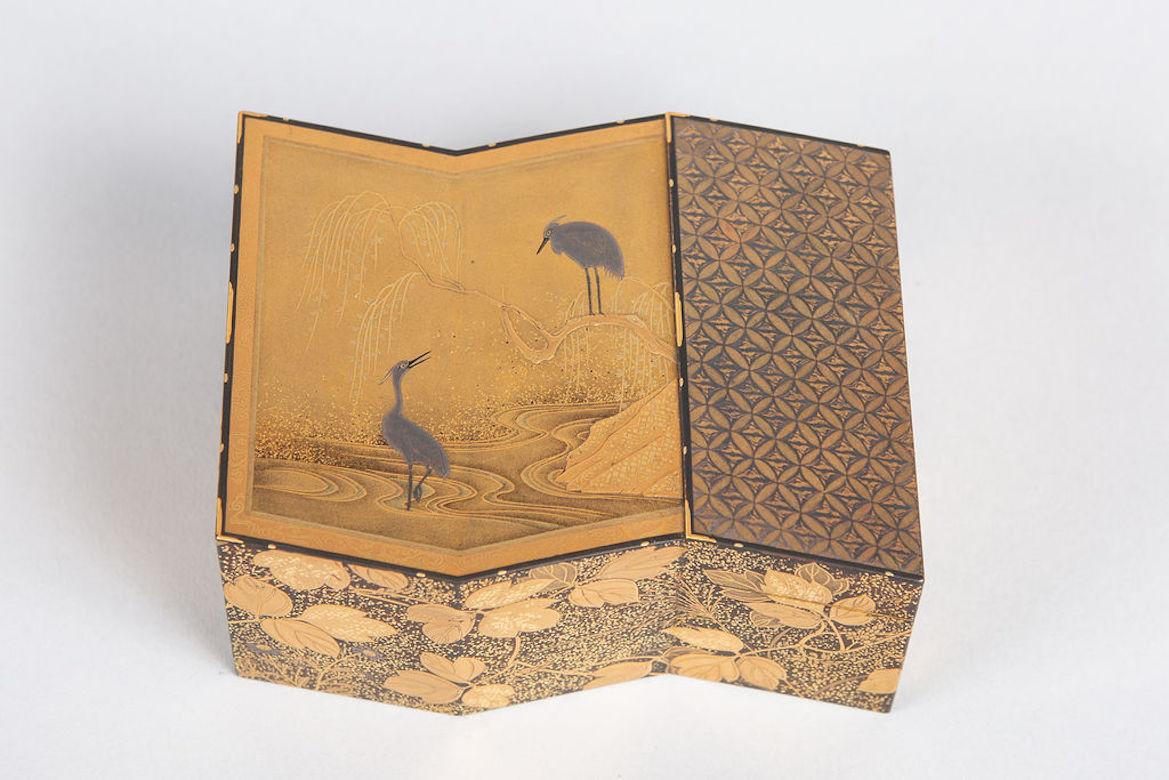

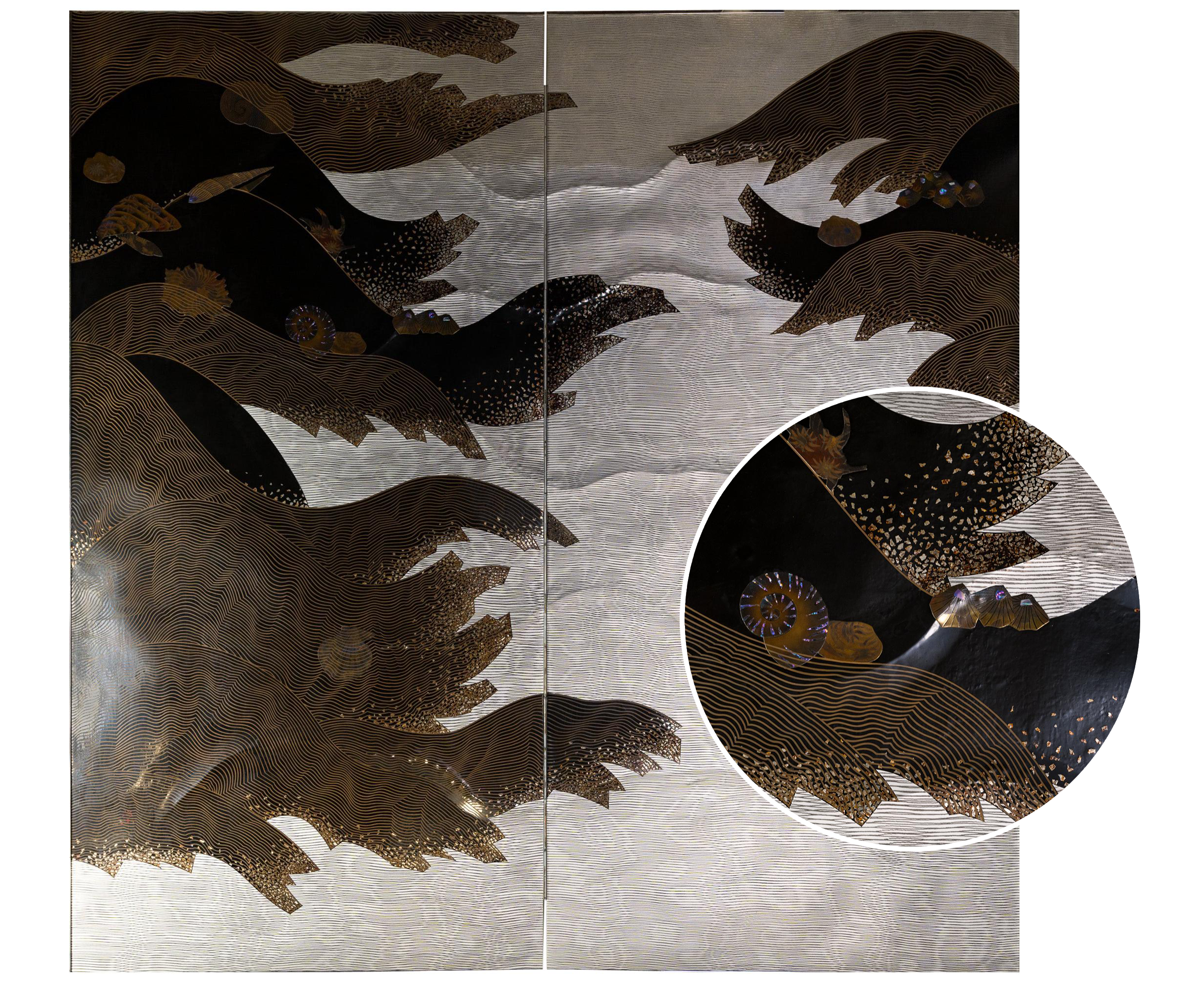

Also in this group is a piece that looks almost contemporary: a 17th-century incense burner boasting an elaborate geometric basket-weave pattern. Another modern-seeming recovery is a striking mid-20th-century silvery screen depicting an underwater scene, with kelp undulating in the current above a seabed covered with scallops, conches and sea anemones.

Lacquer fans include top designers, like Marinaccio clients Michael S. Smith, who decorated the Obama White House, and M(Group)’s Hermes Mallea and Carey Maloney.

Designer Miles Redd waxes rhapsodic about lacquer: “Almost all my rooms have a bit of it to make them more modern, whether it’s peacock, cherry, taxi-cab yellow — my nod to Babe Paley — or chocolate brown, a hat tip to Billy Baldwin.”

Appreciating the craftsmanship of antique lacquerware takes time. You want to luxuriate in the intricate depictions of blossoming plum trees, peonies and chrysanthemums, rising moons and scudding clouds, gold-flecked rivers and mother-of-pearl cranes. If you do, you will be amply rewarded. I lived in Japan for a year with my family when I was 10 and still treasure the lacquer writing box my mother bought me. Inhabited by gold-flecked birds on a black lacquer background, it still seems exotic, beautiful to the touch and striking in profile.

“I have an antique Japanese lacquer box on the center table in my foyer, and it is impossible for guests to walk by this mysterious object without opening it or asking about it,” says collector Renny Reynolds, founder of the New York and Palm Beach society flower shop Renny & Reed.

The Japanese gallery Somewhere Tokyo specializes in post-1960s Japanese design and Italian vintage pieces (by Ettore Sottsass and Memphis Milano, among others), as well as works by contemporary artists. Owner Naoki Sato tries to give new life to antique lacquer he finds on the market. For example, a set of shallow lacquered boxes that once stored cut vegetables in a traditional Japanese kitchen was reworked by artist Ryosuke Harashima into elegant stacking trays with brass highlights. Sato also sells vintage Sottsass flower vases and fruit trays in bright red and turquoise lacquer.

The focus of Lotus Gallery, in Austin, Texas, is Asian antiques. It was founded in 2001 by Francisca Tung, but it is her son Jonathan Tung who is most passionate about old Japanese lacquer. “Lacquer has always fascinated me because it’s used on the most utilitarian objects but is also high art,” he explains. “I’m attracted to the variety of its uses and the mastery of the lacquerers.”

Tung is particularly proud of acquiring an elaborate 19th-century smoking box. It has two sections on top — one for heated coals and one for matches — and three drawers below, for accessories: pipes, tobacco, used matches, ashes. The piece is decorated with golden plum blossoms, signifying rebirth and the new year, as well as cranes, symbols of longevity. “The Japanese developed a whole ritual about pipe smoking,” he says. “They formalize everything.”

Lotus also has a rare 19th-century lacquered koro (incense burner or censer). Its cylindrical stoneware body, topped with a copper lid, rests on three V-shaped legs. The exterior is covered in a thin coat of brownish-red lacquer. Geometrical patterns of inlaid mother-of-pearl frame three cartouches containing a peony blossom, two scholars strolling in the woods and a seaside vignette.

“No one I’ve talked to has ever seen one like it,” Tung says. “It’s pretty impressive that it survived.”

The Manhattan gallery Maison Gerard is known for Art Deco antiques designed by such French masters as Jules Leleu and Jean Dunand. Less familiar are the names of the artisans who did the lacquerwork for them.

After the Universal Exposition of 1900 in Paris, Japan proudly sent top lacquer craftsmen to France, where they met celebrated French designers. Seizo Sougawara worked with Eileen Gray and Jean Dunand. Katsu Hamanaka worked with Jules Leleu, Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann and Jacques Adnet.

Maison Gerard has two pieces by the Leleu-Hamanaka team: an Art Deco walnut cabinet whose four doors were lacquered by Hamanaka in 1933 and a set of three sublime lacquered nesting tables, circa 1925.

The gallery is also selling contemporary Japanese-style lacquer by the husband-and-wife furniture makers Zelouf & Bell. The vibrant chrysanthemums in their Kiku Variation line of trays were inspired by colorful vintage kimono prints and works by Pop artists Takashi Murakami and Andy Warhol.

Such exquisite polychrome works appeal to decorator Caitlin Murray, who founded Black Lacquer Design in Los Angeles. “Color is very important to me,” she says. “My generation in California finds neutral colors crowd-pleasing. Not me.

“I find lacquer has a timeless aesthetic,” she continues. “I shop for antique lacquerware in L.A., on 1stDibs, all over. I’m old-fashioned. There is something about the depth of lacquer that is not like paint. Lacquer is an easy way to make a room exciting.”

Japanese lacquerware was so renowned centuries ago that the technique was termed japanning. The pieces have been popular in the West since Portuguese explorers arrived in Japan in 1543 and began exporting them from Nagasaki to Europe. The Dutch followed suit. Just as lords and shoguns in Japan had privately employed lacquerers to produce household objects for their palaces in the Edo period, 18th-century French royals commissioned cabinetmakers like Jean-Henri Riesener to incorporate antique Japanese lacquer into their cabinets.

In 1853, Commodore Matthew Perry led a fleet of U.S. Navy warships into what is now Tokyo, forcibly opening Japan to American trade. Two decades later, in 1876, the Meiji regime organized a Japanese pavilion and garden for Philadelphia’s Centennial Exposition. It was wildly popular. Two wealthy Philadelphians later donated to the city’s Fairmount Park a Buddhist temple gate, which became a beloved landmark for Japan-crazy Americans. The 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago further stoked American interest in Japanese decor, including lacquer objects. The fair made a big impression on painters, Art Nouveau designers and architects like Frank Lloyd Wright, who collected lacquer vases and incorporated them in the decor of his homes.

But did these new admirers appreciate how labor-intensive and time-consuming lacquer is to produce?

Lacquer is a complex resin made from the sap of the lacquer tree, a member of the sumac family that’s found throughout Japan. The sap is toxic, and before modern handling methods were developed, craftspeople endured bouts of poison-ivy-like blisters and rashes before gaining immunity to it. It is harvested only in small quantities, and the trees must be tapped, very carefully, in summer.

Once collected, the sap is filtered and purified. It takes more than three years of aging to achieve a translucent lacquer with the consistency of honey that can then be tinted black, red, yellow, green or brown.

Lacquer can be applied to almost anything: a wood base, stoneware, leather, bamboo, basketwork, paper, metal, hemp. After a coat has been added, the object must be dried in a place with a of temperature between 77 and 86 degrees and a humidity level of 75 to 85 percent. Once dry, it is polished and another layer applied, and so on, in process that can take weeks. A small tray with perhaps 25 layers could take a year to finish.

The results are worth the wait. The refined, elegant pieces painstakingly created by lacquer artisans are both dazzling and durable and will continue to be coveted for centuries to come.