May 29, 2022For more than 25 years, Chicago-based collector and gallerist Betsy Nathan has been enriching her gallery, Pagoda Red, with East Asian creations. Her particular focus is Chinese furniture and artifacts from the mid-18th through 20th centuries. But, unusually, Pagoda Red also carries contemporary art by local and international artists. It’s a mixture that reflects Nathan’s belief that handcrafted objects have the ability to strengthen our understanding and awareness both of the present moment and traditions of the past.

Nathan’s interest in art dates back to her childhood in suburban Chicago. Her mother, Ann Nathan, ran an eponymous gallery in the city (after managing an entirely different business for 25 years) and filled their house with a heady mix of tramp art, antique furniture, folk objects and contemporary works.

“My mother was a pioneering gallerist and a huge inspiration to me,” Nathan says. “In the late nineteen fifties, when it was still frowned upon for women to work, Ann forged her own path as an entrepreneur. She had a great interest in self-taught artists and showed many at her gallery, including Howard Finster, Minnie Evans and Mr. Imagination. Early on, she also became involved with the Chicago Imagists and later helped found the Sculpture Objects and Functional Art Fair.”

Like her mother’s, Nathan’s curatorial approach is both instinctive and autodidactic. After earning a degree in philosophy from Hamilton College, in Upstate New York, she felt an irresistible pull toward China. “I can’t explain why, but it’s just where I needed to go,” she says of the urge that led to her initial two-year stay in Beijing.

Keen to fully embrace the new culture, she learned conversational Mandarin and eschewed the tourist hot spots in favor of exploring the city’s historic narrow streets, known as hutongs, where she mixed with antiques traders and artisans.

“My mentor was a man with no formal education who, during the Cultural Revolution, had made a living repairing furniture. Decades later, he became an antique furniture expert,” she says. “I would go where he went, and through him, I learned about the symbols and motifs attached to these pieces, as well as the fine craft of woodcarving, lacquering and joinery. Pretty soon, I knew the lingo. I couldn’t talk politics, but my furniture vocabulary was great!”

Since then, Nathan has traveled extensively around East Asia, seeking rare treasures and amassing an enviable collection of pieces, from 20th-century Japanese sake casks to Chinese Qing dynasty hat boxes. She selects each object for the story it tells, imbuing it with a sense of mystery and eccentricity.

“In the West, we often think of Chinese furniture as very ornate, because this style was applied mainly to pieces destined for the export market,” Nathan says. “Furniture made for the domestic setting was elegantly restrained and inspired by the same minimalism you see at the end of the Ming era [16th century]. The furniture I have collected is impeccably made, with no nuts, bolts or nails. If you took it apart, it would be as beautiful as it is when it’s perfectly assembled.”

Nathan’s palpable passion for the items she acquires betokens a deep appreciation for ancient customs and material culture. “I love early Chinese wooden headrests,” she explains. “You can look at a hundred of them, and each one would be different, made to suit a different person’s proportions. It is these artifacts, with unusual configurations or functions, that speak loudest about the connections between people. When things are genuine and rich like this, their character only improves with time.”

Here, Nathan talks with Introspective about some of her most evocative pieces from both past and present.

You founded your gallery in 1997, which was a bold thing to do given that you were only in your mid-twenties at the time. What made you want to turn from being a collector to being a dealer?

China isn’t the easiest place to live, but for me, it is undeniably the most compelling. I realized very quickly that antique Asian furniture making wasn’t just a functional pursuit. Artisans were like architects: Objects had purpose and great thought attached to them. For example, eighteenth-century Chinese desks designed for poets and scholars would often feature specially sized drawers and shelves for their scrolls. Some might have been accessorized with glorious inkstones decorated with birds denoting the beauty of springtime meditation.

Discovering these eccentric avenues outside of the norm is when furniture got interesting for me. If you embrace an entrepreneurial spirit, you have to have the courage to just go out and make things happen. Plus, I always figured that if something went wrong with my business, I would at least be surrounded with things that I loved. I have never shopped according to what other people might want. It’s all about the visceral for me.

Was it easier to source rare objects and furniture back then?

Times have changed, and so have mentalities. In the early nineties, there was a lot of superstition attached to antiques. Most people in China didn’t want objects that carried the lives of others in them — they didn’t know what spirits were entering their homes. The Chinese market has changed, and China has changed, too. Heritage, and that includes antiques, is now celebrated, and I often find myself educating young Chinese people about ancient crafts, because, for many, their lives have moved so far from even recognizing these traditions.

Where do you now source your collection pieces from?

It’s almost impossible to find the rarities I once did directly from [merchants] in China, but I still go back, and I love the hunt. What’s been fortunate for me are the long-standing relationships I’ve formed with international collectors, sometimes stretching back decades.

They, like me, had the opportunity when they were younger to purchase things and create incredible collections. At a later time in life, these experts have often trusted me with their treasures. Recently, Pagoda Red acquired a very interesting collection of incredibly unusual and ornate nineteenth-century tabako-bon [Japanese smoking sets].

Pagoda Red carries contemporary art as well as East Asian antiques. Why did you decide to blend old with new?

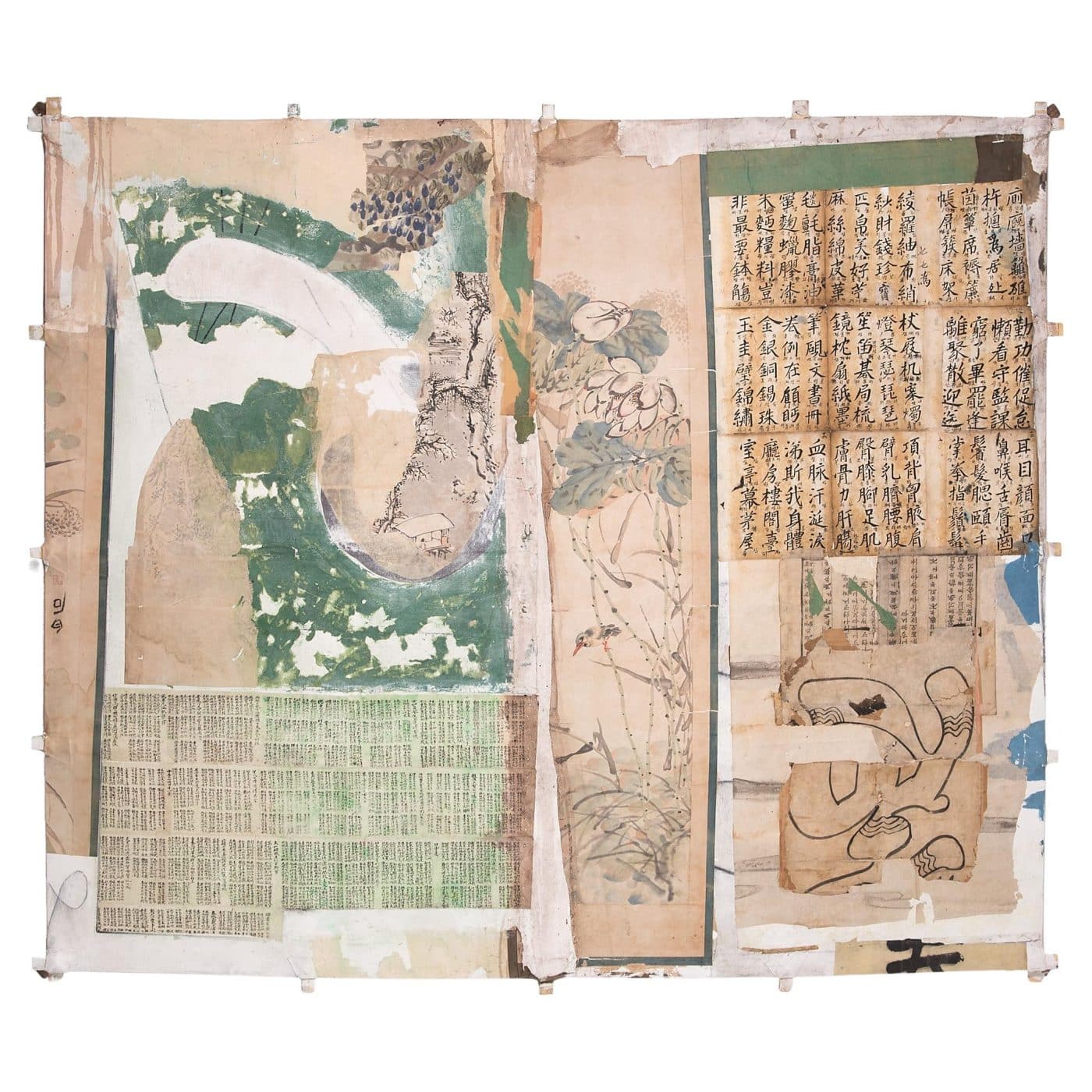

I’m always drawn to artists who have an Asian sensibility. For example, Michael Thompson, who is a Chicago artist, creates kites from muslin and vintage Asian ephemera, such as fragments of fabric, scrolls, drawings and handmade paper. He’s actually a motorcycle dude, but his art is so ethereal and delicate.

We also represent Japanese artist Toyoharu Kii, who studied traditional mosaic making in Italy. He was the first artist to introduce this ancient decorative craft to his native country, which he blends with the tradition of Japanese sumi-e ink painting. So again, we have a cross-cultural spirit that lives simultaneously in the past and in the present.