January 17, 2021Today, nothing remains of the house and studios where Art Deco master Jean Dunand lived and worked for most of his life. The buildings on rue Hallé in Paris’s 14th arrondissement were sold to a real estate developer in the 1950s and entirely demolished. In their time, however, they constituted a world unto themselves.

The structures occupied a whole block and incorporated, among other things, a showroom and a climate-controlled space for lacquer pieces (which need humidity in order to dry to a high gloss). A double door led from the family dining room directly into Dunand’s office. “As soon as a meal was over, he’d go immediately back to work,” recounts one of his grandsons, Jean-Paul Dunand.

The complex was also something of a mini menagerie. He kept both pigeons and chickens; the latter’s eggshells, crushed into tiny pieces, were used to decorate many of his lacquer creations. More unusually, an ocelot named Toya — a present from a South American client — lived in a cage in the courtyard and ate four pounds of meat per day.

Dunand was one of the most extraordinary and emblematic designers of the early 20th century. He produced well over a thousand designs in an almost dizzying array of media. He is best remembered for his exquisite creations in lacquer and metal, but he also worked as a sculptor, mosaicist, portraitist and goldsmith. He imagined jewelry, tapestries, fabrics for haute couture and, during World War I, even a helmet for soldiers with an adjustable visor.

In 1927, he was commissioned by the multimillionaire Charles Templeton Crocker to decorate the majority of his San Francisco apartment’s interiors (Jean-Michel Frank oversaw the entry and main sitting room; Dunand, the rest). “His paneling for the breakfast room remains unforgettable,” says Benoist F. Drut, of the New York gallery Maison Gerard. “It was not unlike an aquarium: all black lacquer, with exotic fish swimming around.” Back in 2000, Maison Gerard sold the panels to jeweler Fred Leighton, who installed them in his Madison Avenue boutique.

Dunand “was something of a jack of all trades but gifted in everything he did,” says Paris-based designer expert Amélie Marcilhac, who coauthored a monograph titled Jean Dunand with her father, Félix Marcilhac. Published in November by Éditions Norma and currently available only in French, it not only masterfully showcases the breadth and quality of the designer’s production and relates his rich life and career but also provides a catalogue raisonné.

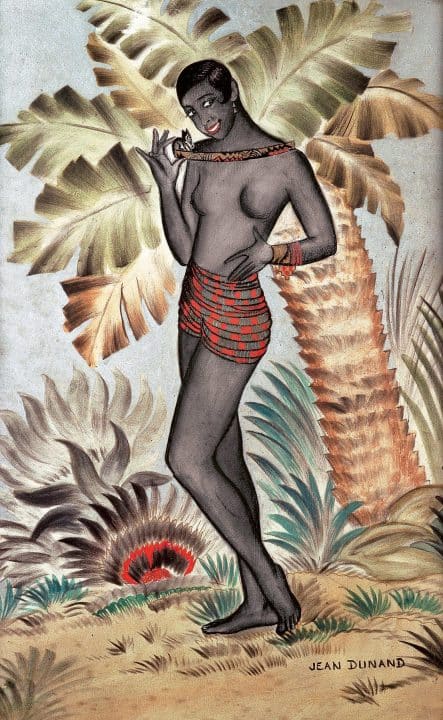

Dunand’s clients included fashion designers Jeanne Lanvin, Madeleine Vionnet and Elsa Schiaparelli, as well as Josephine Baker, who used his vases and screens for her stage sets. She also posed nude for him, and her likeness appears on several lacquer panels. He collaborated with Robert Mallet-Stevens on a boutique for the Swiss leather-goods brand Bally on Paris’s boulevard de la Madeleine, and he lacquered furniture for both Eugène Printz and Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann.

The two highlights of his professional life, however, were no doubt his participation in the Exposition international des Arts décoratifs et industriels modernes in Paris in 1925 and the decor he imagined for a number of luxury ocean liners, the largest and most prestigious of which was the Normandie, which first set sail in May 1935.

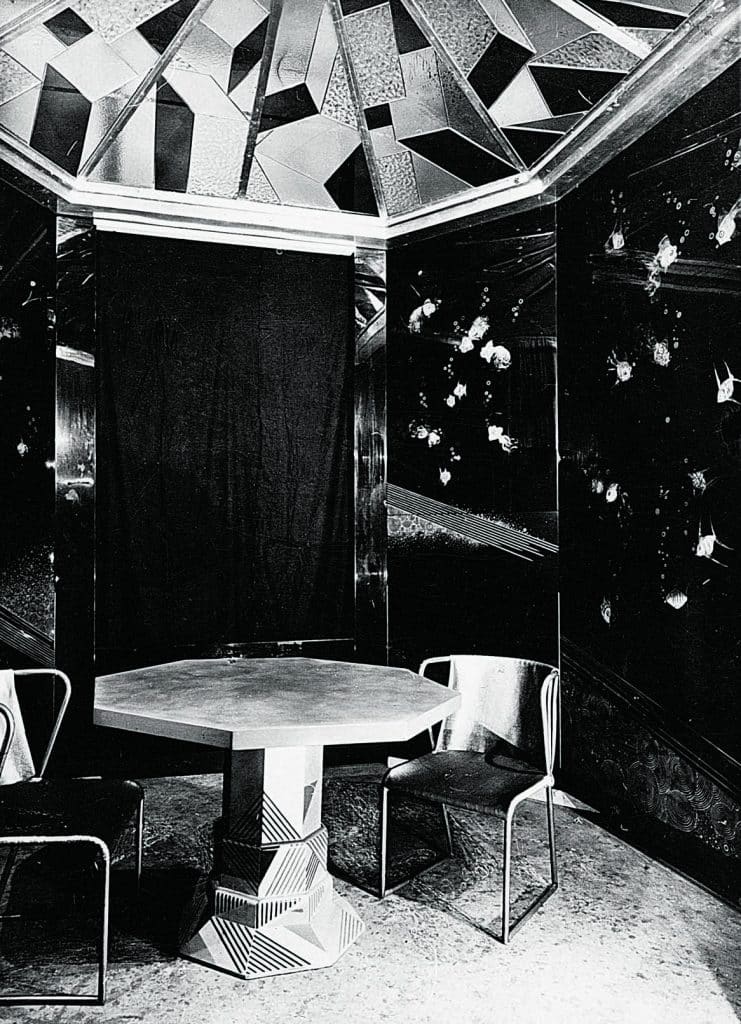

At the 1925 exhibition, from which Art Deco derives its name, Dunand made his mark not only with a series of four monumental hammered-copper vases, decorated with striking geometric patterns in lacquer consisting of squares, triangles, chevrons and undulating lines, but also with the sleek and stylish smoking room he designed for the Pavillon de la Société des Artisans Décorateurs.

The latter featured a daybed upholstered in lacquered leather and a chest embellished with a cat motif. After visiting it, the couturier and collector Jacques Doucet wrote to Dunand, proclaiming that it was “the affirmation of the great artist that you are.”

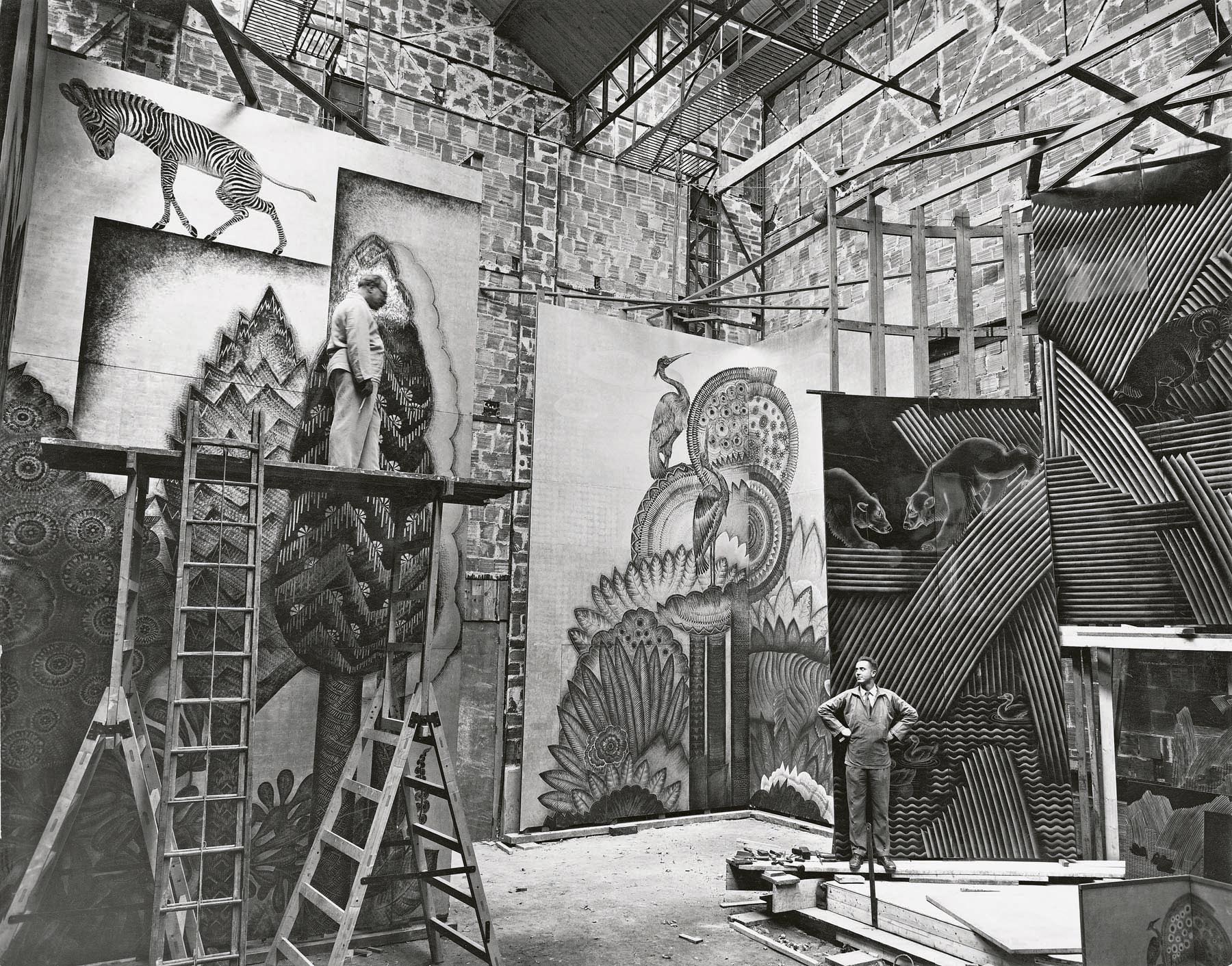

Dunand’s main commission for the Normandie was another smoking room, this time with the proposed theme “the games and joys of man.” His response was a set of five gold-lacquered screens, each almost 20 feet high.

To accommodate their height, he dug ditches in the basement of his rue Hallé workshops and installed a pulley system that allowed him to raise and lower them. He also made them out of a personally developed mixture of plaster and earth he called sabi, which could resist fire up to 1,500°F for a duration of two hours. (Another liner on which he had collaborated, the Atlantique, had been destroyed by flames in 1933, less than 16 months after its maiden voyage.)

“What makes Jean Dunand’s work special to me is how he was able to create a chic Art Deco fantasyland with his lacquer panels,” says Jake Baer, the CEO of Manhattan gallery Newel. “The animals and scenes he created had a distinctive Cubist look, which is iconic.”

Born Jules-John Dunand in 1877 (he Frenchified his first name later) close to Geneva in Switzerland, his first career was as a sculptor. He moved to Paris in 1897 and won a gold medal at the Exposition universelle de 1900 for a bronze proof titled Quo vadis. Five years later, he had turned his attention almost exclusively to the decorative arts. In an ensuing interview, he explained, “The desire to earn a living was partly responsible for my abandoning what is known as ‘fine art.’ ”

He first made a name for himself with metal vases and vessels largely in the Art Nouveau style. “I particularly like the refined early vases,” says Drut. “They already denote his level of excellence.”

In 1912, Dunand met the Japanese lacquer master Seizo Sugawara, who initiated him into the secrets of the medium’s age-old techniques. It was not until 1921, however, that he presented his first pieces of lacquer furniture. Dunand was not the only Art Deco designer to use the material (Eileen Gray famously did so too), but he employed it much more prolifically and decoratively.

By 1924, he was at the head of a workshop of nearly 60 employees producing objects that ranged from boxes and trays to card tables and screens, many of which bore breathtakingly beautiful motifs consisting of interlocking lines and geometric shapes. By 1927, he had abandoned abstract patterns, favoring instead rich and complex figurative designs, largely featuring animals against stylized backgrounds of leaves and flowers, an aesthetic not far removed from the paintings of Henri Rousseau.

The Normandie turned out to be the zenith of Dunand’s career. To produce the 1,035 different elements involved, he allowed himself just four hours of sleep per night. His health suffered afterwards, as did his business, a casualty of both changing fashions and the economic downturn of the 1930s. Yet Dunand continued his work relentlessly until his death, in 1942 at the age of 65.

“It completely absorbed him,” recalls Jean-Luc Tahon-Dunand, another grandson. The designer would rarely take a weekend off, and summer vacations would last no longer than a week. It however didn’t stop him from having fun. “He was a simple man with the soul of a child,” notes Jean-Paul Dunand. “He got amusement out of playing practical jokes.”

After World War II, Art Deco went completely out of style, and Dunand’s work was largely neglected until the mid-1970s. Since then, it has gained something of a cult following. Karl Lagerfeld, Yves Saint Laurent, Andy Warhol and Marc Jacobs all had Dunand creations in their collections.

In a 2009 interview, Saint Laurent’s longtime partner, Pierre Bergé, recounted how he and Saint Laurent first become enamored with the work of Dunand. “We were driving down rue Bonaparte [in Paris] with me at the wheel when Yves shouted: ‘Stop! I’ve seen some extraordinary objects!’ ”

In a window, he had spotted two of the monumental vases Dunand created for the 1925 exhibition. The couple snapped them up for 5,000 francs (the equivalent of $8,120 today). When Christie’s sold their collection in February 2009, the pieces went for almost $4 million.

Today, some of Dunand’s most sought-after works are the so-called ailette vases dating to the mid-1920s, onto which he affixed protruding lacquered-metal discs. One sold at Sotheby’s New York for $596,000 in December 2019. “There were few of them produced,” says Amélie Marcilhac, “and they’re appealing because of both their geometric forms and their great technical prowess.”

In February, a set of 18 panels from the Normandie will be offered by auctioneers Philippe Revol and François Xavier Allix in Le Havre, France, with an estimate of between $304,000 and $365,000. Baer still recalls being struck as a young boy by the images his father showed him of the liner’s smoking room, which featured the pieces. “The Normandie was essentially a floating palace,” he marvels, “and these panels are a big reason why. For me, they’re a superlative example of Dunand’s brilliance as an Art Deco master.”