April 18, 2021Context is everything when it comes to art. For a sculpture, an outdoor setting on a lawn or in a garden can open up a whole new world of beauty and meaning. Nature is a powerful setting, and a tricky one, but if a collector knows how to handle an outdoor piece, the rewards are many.

The acclaimed Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama, 91, has become a phenomenon, especially in her later years, on the strength of her universally appealing polka-dot pumpkins, not to mention her mirror-filled “infinity rooms,” and her sculptures are never more captivating than when they are turned into large-scale outdoor works.

A new exhibition at the New York Botanical Garden, “Kusama: Cosmic Nature” (on view through October 31), proves the case with four major pieces on view, three of them outside, including Infinity Mirrored Room — Illusion Inside the Heart, 2020, which reflects its leafy environment. Her famed work Narcissus Garden, 1966/2021, a field of mirrored orbs, nestles in and amplifies the wonders of the Native Plant Garden.

The show will no doubt bring many visitors to the 250 acres of the Botanical Garden, but what about the view around your own garden, near the pool out back or in the field beyond?

The pleasures of adventurous and striking contemporary outdoor sculptures are open to everyone, even those with a small apartment terrace, and more collectors are taking advantage of the genre these days — especially during a pandemic when alfresco time is embraced and enjoyed by necessity.

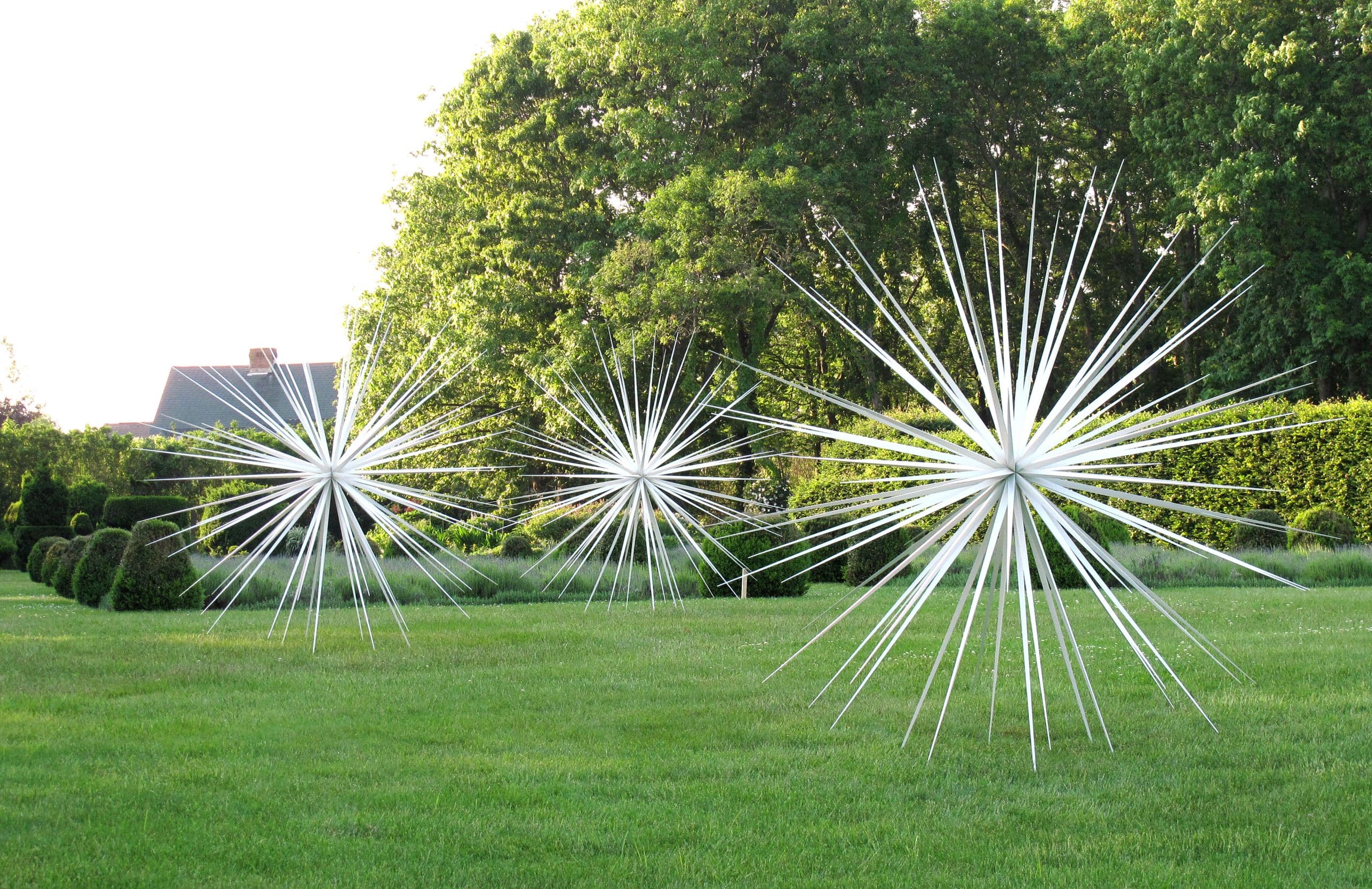

“With outdoor sculpture, the placement becomes part of the piece,” says Cheryl Sokolow, who founded C Fine Art of New York City and the Hamptons in 2009.

Sokolow specializes in en plein air work at her gallery, and she even organizes public shows of these pieces, such as the “Uncommon Ground” series, the latest edition of which debuts at the Bridge Gardens in Bridgehampton, New York, on June 8.

“My practice is based on formalism,” Sokolow says, citing her fondness for artists like Kevin Barrett, who is popular with her clients on 1stDibs and makes striking abstract pieces in stainless steel with lots of biomorphic curves, bringing a shiny edge to verdant outdoor spaces in the Northeast and beyond.

The Connecticut-based landscape architect Janice Parker has a motto for placing art outside: “Don’t ‘plop and drop,’ ” she says of the mistake of placing a work alone on a lawn. “I try to make a room of plants for each sculpture. You have to mass something so they don’t look like they’re coming out of the ground.” One of her tricks is to plant the shrub weigela, which blooms pink in spring, making an especially lovely reflection on a polished steel work.

“You don’t want to compete with a sculpture, but you have to create a moment,” she says. She loves Grounds for Sculpture, the 42-acre sculpture park and museum in Hamilton, New Jersey, because “for every sculpture, there’s a corresponding horticultural gesture. It might be small, but it’s there.”

Lighting is an oft-forgotten element, Parker says, given that people are home in the evening and want to appreciate the art. Her tip is to plant some low ground cover: “It hides the lights, and you don’t have to mow around them.”

In Santa Fe, New Mexico, Glenn Green founded his eponymous gallery in 1966 with his wife, Sandy, and he says the focus on outdoor works has only grown since he started. “People are improving their homes and grounds, and the spaces are getting bigger,” he says, adding that outdoor sculptures comprise more than half of his business.

But it’s not just homeowners who are buying these works; museums, businesses and municipalities need to beautify their outdoor areas too. “We place a lot of public art, and that’s important to us,” Green adds. One example is Navajo artist Melanie Yazzie’s Two Minds Meeting, 2016, a joyous figurative work in red-painted aluminum that now stands in a park facing the silvery waters of Lake Loveland, Colorado.

Green’s daughter, Kerry, the gallery director, adds that clients are aided in their selection by the fact that they can examine the goods in their large, five-and-a-half-acre sculpture garden. “It makes such a big difference to people for their decision,” she says.

Valley House Gallery & Sculpture Garden in Dallas follows suit, boasting four and a half lush, wooded acres for just that purpose, currently featuring pieces by Charles Umlauf, Nat Neujean, Deborah Ballard, Alex Corno, David Dreyer and Michael O’Keefe.

Chery Vogel, who runs Valley House with her husband, Kevin, notes that their taste runs toward the figurative — like Continued Conversations, 2002, by Deborah Ballard, depicting two life-size seated people — as well as pieces made up of smaller components.

“I like sculpture that is generally a single piece or small group of associated things,” says Vogel. One example is Charles T. Williams’s Iron Cesters III, with three totemic forms.

That brings up the issue of scale — outdoor pieces can be huge, but that doesn’t mean they should be. A lovely small work doesn’t necessarily improve when its scale is increased by a factor of five.

“I rely on the artists for scale. That’s their craft,” says Sokolow. “Many of them start with a maquette.” She also uses Photoshop to show clients how a piece will appear in situ in a garden or other setting.

“Scale is so tricky,” says architect Brent Leonard of the New York–based 1stDibs 50 firm FormArch, which specializes in high-end residential work. Even if it’s placed alongside tall trees, a sculpture “should be more human scale,” he adds. A 50-foot-tall Mark di Suvero bronze may appeal at Storm King, but probably not in the backyard (unless you call Versailles home).

Leonard’s overall approach to outdoor works is to create “subtle contrasts,” he says. “Often, we place sculptures in architecture settings like courtyards and gardens, with a lot of orthogonals,” or right angles. “In those cases, I like to do something anthropomorphic, with curves and humanistic forms for contrast.”

“The first thing I do when I want to turn a field into a sculpture garden is plant some trees,” says gallerist Caryln Moulton. “Sculpture needs to be embraced. On its own, it looks lost.”

And the opposite is true too. For a poolside spot in the “secret sunken garden” of a streamlined farmhouse in Sag Harbor, Leonard wanted to play off the rounded shapes of the hydrangeas, so he went with a very linear piece: I Beam, a steel sculpture by James Prestini, is composed of angular beam segments. “It looks so strong,” Leonard says.

Nicholas Yust, an artist and sculptor who sells his own work as well as that of others in his eponymous Cincinnati gallery, takes commissions for large outdoor works, and he’s known for the richly textured surfaces of his abstract metal pieces.

When a client asks for a larger version of one of Yust’s abstractions for an outdoor setting, one thing they don’t necessarily think about is the nexus of scale and texture. “You can change the height and diameter, but the grinding pad I use on the surface isn’t any bigger, and the texture won’t scale up,” he says.

Not likely a deal breaker, but something to keep in mind as to how the final piece will look. The golden rule for the sculpture and its installation, Yust says, is to “maintain a sense of balance” between the home, the vegetation and the art.

When it comes to materials, there’s a fairly limited universe, given that Mother Nature can take a toll on outdoor works; metal and stone tend to be the go-tos.

Nico Cobelens, founder of the gallery Colonia Art of the Netherlands and Denmark, is very particular about the artists he works with, favoring those who use extra-thick German steel, as in some of the works he offers by sculptor Stefan Traloc. “These pieces are living outside, so we avoid cheaper quality,” says Cobelens.

Caryln Moulton, founder of the Canadian gallery Oeno (so named for its location in the wine country of Lake Ontario’s northern shore), notes that “salt air is an enemy. It corrodes. Though we’re in the middle of the country, we have clients on both coasts, and it’s something to be thoughtful about.”

Moulton sells the work of some two dozen artists but notes that “sculpture is my first love.” She shows that affection by lavishing attention on her five-acre gallery property, which is dotted with sculptures and attended to by two full-time gardeners.

Clients love to put metal sculptures by their swimming pools, but Moulton advises caution: “Being visible from the pool is good, but not too close — chlorine and salt will splash out of it and can harm a work unless it’s made of marine-grade stainless.”

That said, not all water is the same. Parker notes that “suspending a sculpture in a reflecting pool goes back to the Greek and Romans. It’s ethereal and always brings a smile to your face.”

Moulton’s version of avoiding the “plop and drop” is to think big. “The first thing I do when I want to turn a field into a sculpture garden is plant some trees,” she says. “Sculpture needs to be embraced. On its own, it looks lost.”

Color is a way to invigorate an outdoor work, as the dealer Mark Dean of Miami’s Dean Project knows well. “I work with around 20 artists, and the look of the outdoor works is clean, colorful and contemporary,” he says of his roster. His tip for buyers of outside sculpture is to realize that “maintenance will be required,” he says. “There’s no way around it.”

One of the most ebullient artists Dean works with is the irrepressible Hunt Slonem, he of the ever-evolving bunny motif. Color is integral to Slonem’s practice, and when he makes a big outdoor bunny, oftentimes the stainless-steel-and-aluminum piece gets coated in a glossy enamel paint used on cars. “It adds to the controlled chaos of the work,” says Dean — and to the fun factor.

If rust is a worry for a collector, Dean also represents Phillip Maberry, whose trompe l’oeil fiberglass “Pool Toy” sculptures were practically made to loom behind a diving board or along a seashore.

When issues of placement, maintenance and aesthetics all come into alignment, outdoor sculptures can be a transformative possession. As Moulton puts it, “It should look effortless, elegant and create a moment of contemplation and surprise.”