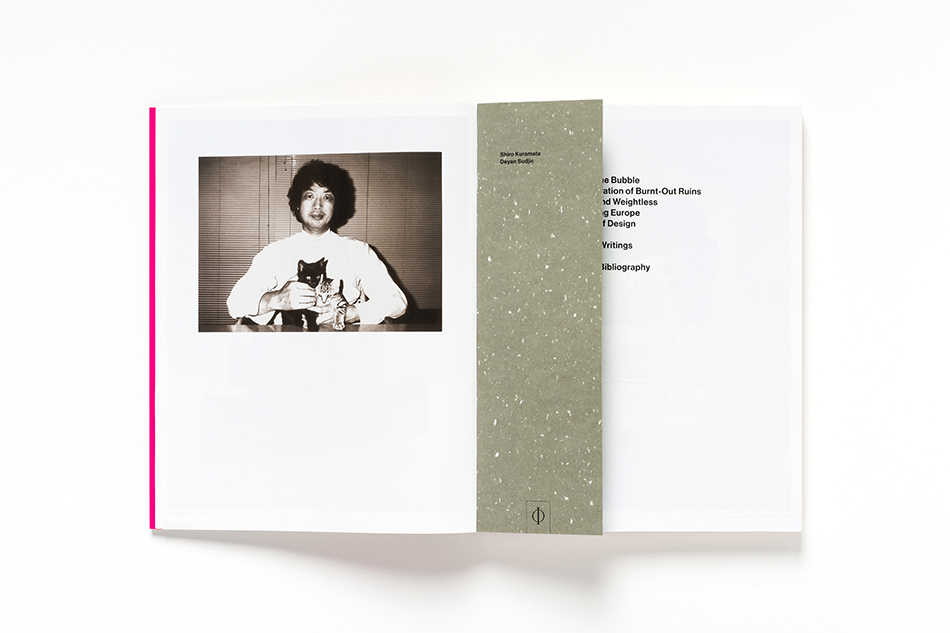

Kuramata constructed the Glass Chair using a brand-new adhesive that could connect pieces of glass after being exposed to ultraviolet rays. Above: The forward-looking 20th-century Japanese designer Shiro Kuramata, seen here in 1979, is the subject of a comprehensive new monograph from Phaidon. Photo by Kazumi Kurigami

July 17, 2013They say you shouldn’t judge a book by its cover. But then again, sometimes the packaging tells you something vital about what’s inside, and that’s certainly true of Deyan Sudjic’s new double-volume Shiro Kuramata (Phaidon), which comes enclosed in a chic, polychromatic acrylic box.

Acrylic was a key material for Kuramata (1934–91), one of the brightest lights of Japanese design in the 20th century — and someone who had a subtle but pervasive impact globally in the fields of furniture and interior design. From the moment Kuramata started overhauling the visuals for a Tokyo department store the late 1950s, he wanted to be on the leading edge of design’s future, and, based on the evidence presented in this book, he succeeded.

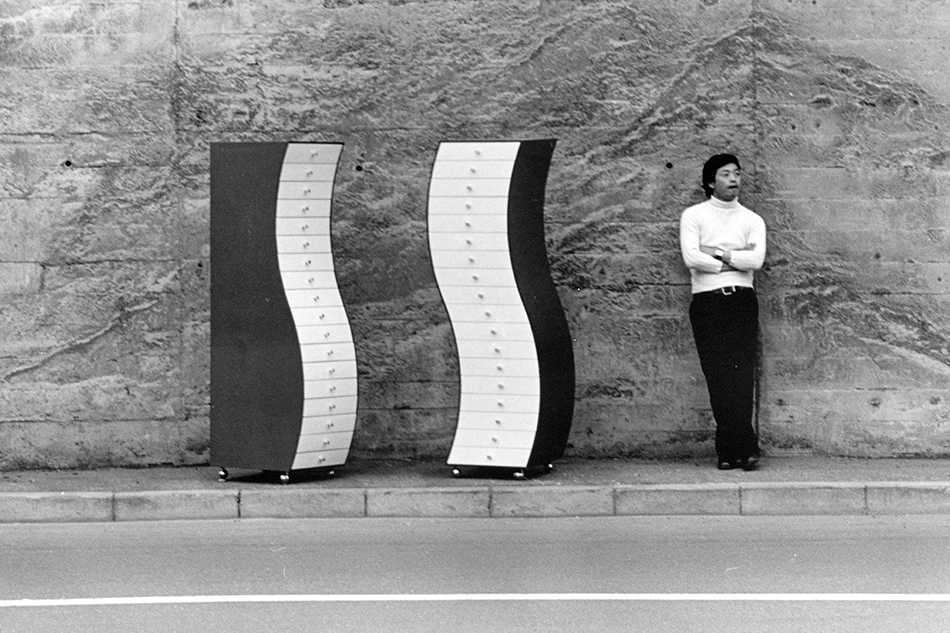

Some of Kuramata’s most famous pieces include Furniture in Irregular Forms Side 1, 1970, which may be known to you as “that serpentine, wavy dresser,” a witty gesture in plywood that gained fame when Cappellini starting reproducing it in the 1980s. There’s also the Miss Blanche chair, 1986, a Tennessee Williams–inspired clear acrylic armchair embedded with bright red artificial roses, and the Glass Chair, 1976, an elegant concoction comprised solely of six panes of greenish glass bonded together with invisible glue. The Glass Chair was actually Kuramata’s response to his disappointment with the vision of future furniture offered in Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Sudjic, the director of London’s Design Museum and a prolific author, only met Kuramata once, in the 1980s. “I was fascinated by the purity and beauty of the work,” Sudjic says today, adding that he has been wanting to do a book on the designer for more than 20 years.

Kuramata and colleague outside his studio in 1975. Photo courtesy of Kuramata Design office

Shiro Kuramata is meant to be the definitive monograph, featuring 600 designs, including all 180 furniture pieces (a sleek riot of acrylic, steel and glass). Sudjic’s comprehensive essay starts off with a discussion of Japan’s 1980s economic bubble, which enabled Kuramata to gain fame, and then moves to his first experience of the work; only 50 pages in does the reader learn when and where the designer was born. The deep-dive of context proves to be fruitful, however, as when Sudjic points out that the very idea of a chair is alien to traditional Japanese design. Kuramata had a particular talent for joining disparate East-West influences.

Kuramata’s unorthodox interiors, particularly bars and clubs, might well be the book’s biggest revelation. Many people may have experienced his spaces when inside Issey Miyake shops around the world, including at Bergdorf Goodman in New York in 1984, but they likely didn’t know who was behind the highly specific look. (One of the Kuramata’s innovations was to lay the Miyake clothes flat on cantilevered shelves instead of hanging them).

Sudjic is wistful about there being only three or so full-fledged Kuramata interiors still extant in Japan. “But a lot of what he did was meant to be transient, and he knew it wouldn’t last,” Sudjic says. “In some ways, I would compare him to Eileen Gray, whose work has become more and more important, even though less and less of it survives.”

Certainly, in the West these days, Kuramata is not a household name, but this Phaidon monograph should move the needle a bit. “Reputations are curious things,” Sudjic says. “My Google Alert just said that the Dallas Museum has now acquired a Miss Blanche chair. So that’s promising.”

Purchase This Book

or support your local bookstore