May 23, 2016Amorphous stoneware vessels, like the one above, are the specialty of Los Angeleno ceramist Adam Silverman (top), who’s currently in the midst of his first New York show at Friedman Benda gallery (portrait by Adrian Gaut). All photos courtesy of Friedman Benda, Adam Silverman and noted photographer

In “Ground Control,” the New York debut of the Los Angeles–based potter Adam Silverman, at Friedman Benda gallery, amorphous stoneware vessels, their surfaces variously scorched or luminously glazed, sit on the earth-colored concrete floor and on charred wooden bases of varying heights. Meanwhile, along the back wall, tie-dyed panels of indigo denim, arrayed with small spheres and smashed masses of cerulean-blue clay, cascade onto the floor. The small, yet striking installation can be read as a kind of flowering desert-scape; a newly birthed galaxy of planets, asteroids and nebulae; or an expressive summation of the lanky Silverman’s curious career journey.

Just as these richly textured and mottled vessels developed gradually — forming first on the wheel and then through repeated accretions and erosions via glazing, firing and grinding — so too did the 53-year-old Silverman circle around the mantle of artist for much of his adulthood, exploring other selves — architect, fashion entrepreneur, commercial potter — that ultimately shaped the maker that he is today. Now confident in his calling and in full creative tilt, he is helping to elevate clay, long ghettoized as the stuff of craft, into an artistic material of the highest order.

A native of Old Greenwich, Connecticut, Silverman discovered pottery at summer camp in his early teens. He liked throwing pots enough to major in ceramics at the University of Colorado, and it was on the strength of his portfolio that he transferred to the Rhode Island School of Design. Yet, like so many others who possess a pragmatic streak as well as an artistic bent, he graduated with a degree in architecture, in 1988.

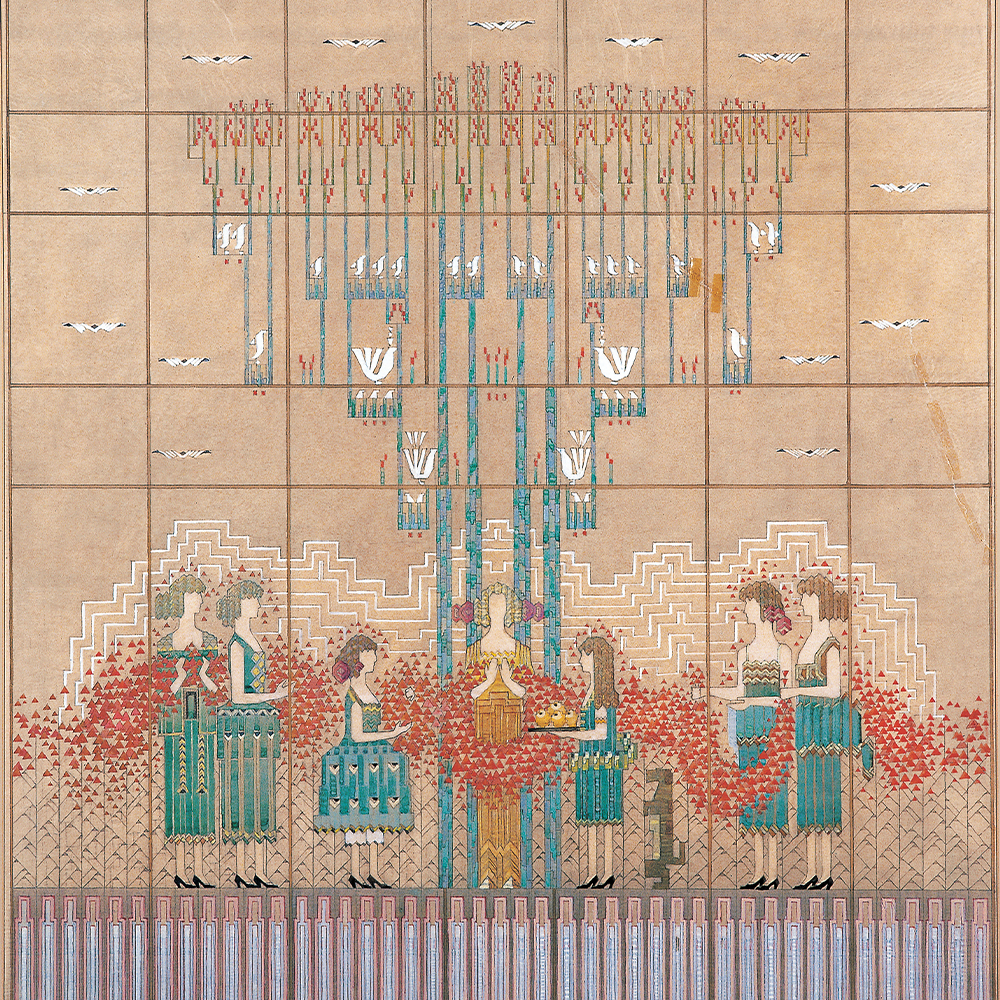

Silverman created 400 glazed clay objects for the traveling installation Boolean Valley: The Geometry of Clay, 2008–10, shown here at the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas. Its arrangement is based on a Boolean-logic pattern devised by architect Nader Tehrani.

So when Silverman first moved out to Los Angeles, it was to take a job with an architecture firm and emulate the modern masters who had infatuated him — Tadao Ando, Louis Kahn, Le Corbusier and Carlo Scarpa — who brought forth new architectural forms in concrete. A few years later, he and an old college roommate decided to open a hangout for young creatives in their then-dreary Silver Lake neighborhood. It included a small bookshop, a barber chair and a back office where they could do their architectural drafting.

Eventually, they decided to sell T-shirts of their own design, softer cotton versions of the kind of workwear they favored. Before long, the T-shirts had morphed into the cult streetwear labels X-Large and X-Girl, spurred by the support of such friends and fans as Beastie Boy Mike D., Spike Jonze, Kim Gordon and Chloë Sevigny. Running a fashion label was more rewarding than the architectural practice of “drafting for dollars,” as Silverman puts it, but by the end of the 1990s he found himself, unhappily, more of a businessman than a designer. For solace, he would retreat to his garage and throw pots.

The cataclysm of 9/11 forced Silverman to face up to his career disillusion. Over the next year, he extricated himself from the clothing business and a marriage and spent the summer at a six-week pottery intensive at Alfred University, in Upstate New York, to see if he could make ceramics a full-time career. “It was a real concern, as I now had two small children to support,” Silverman recalls, adding with a chuckle, “but I’m a gambling man.” He immersed himself in the history of the field, which he’d never done at school, and experimented with different kilns. He emerged from the course convinced he had the chops to make a go of it.

“Remarkably mediocre,” however, is how Silverman today describes the cups and bowls he first made under the name Atwater Pottery. But there weren’t a lot of groundbreaking local potters back then, and Los Angelenos rallied around Silverman’s venture. Savvy about marketing, he soon had stores stocking his pieces nationwide. Yet without realizing it, he’d put himself back in the wholesale business he’d worked so hard to escape. Rethinking his business plan, he eventually targeted his marketing efforts at the city’s top interior designers, inquiring about making custom ceramic lamps and other functional pieces. As they were often furnishing enormous homes, the decorators responded with a new and welcome question: “How big can you make it?”

No one had ever seen vases like these, which were often as ugly as they were compelling.

“I was afraid to make stuff that wasn’t functional,” Silverman says of his early foray into ceramics. Photo by Manfredi Gioacchini

In addition to these commissions, Silverman now concentrated on vases, which were far more fulfilling to craft. He experimented with unusual glazes and pitted and flaked textures expressive of the ferocity of the kiln. “I knew I was hiding from the idea of being an artist,” says Silverman, recalling those years. “But I was afraid to make stuff that wasn’t functional.” Afraid or not, he was emerging as a creative force. No one had ever seen vases like these, which were often as ugly as they were compelling. Meanwhile, their openings kept narrowing.

In 2008, the year Silverman produced his first piece without a hole, he was approached by the renowned Sausalito-based manufacturer Heath Ceramics to become the studio director of its new L.A. shop. The setup served him well, as he was able to be a commercial potter without worrying about day-to-day business, which gave him the head space to experiment and work on art pieces. During this time, Silverman began producing increasingly conceptual installations for galleries in the States and Japan. After five mutually fruitful years with Heath, having refreshed and expanded the 68-year-old company’s repertory of products, he established his own studio in Glendale, this time as a full-fledged art potter.

Gazing at the vessels in “Ground Control,” every one with a distinct presence, a visitor finds it hard not to believe that Silverman had a vision of each in mind when he threw a mound of clay on the wheel. In reality, though, he makes a group of shapes and then sits with them for a long time before deciding which glazes to apply and the method of application. Should he pour or brush the pigment on a vessel, or maybe smear it on, with large scoops of glaze in each hand?

To achieve his unusual surfaces and layers of color, he puts each piece through multiple firings. Not all survive. The risk is part of the art making. And it’s what gives these works a totemic feel, as objects that have endured. The artist Adam Silverman is no longer making vessels but entities.