October 30, 2022More than a decade ago, Bobbye Tigerman, curator of decorative arts and design at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), was organizing the 2011 survey “California Design, 1930–1965: ‘Living in a Modern Way’ ” when she realized that many of the show’s objects had Nordic connections, such as those made by Scandinavian émigrés, like Eero Saarinen, of Finland, and the Swedish-born Hollywood designer Greta Magnusson Grossman. She remembers thinking, “There’s a more national story here.”

That story is now being told in “Scandinavian Design and the United States: 1890–1980,” on view at LACMA through February 5, 2023. Co-organized with Monica Obniski — formerly curator of 20th- and 21st-century design at the Milwaukee Art Museum, where it will make its final appearance from March 24 to July 23, 2023 — it is the first show to address the complex modern design relationship between the United States and all five Nordic countries: Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Finland and Iceland. (Although delayed by the pandemic, it has already appeared at Stockholm’s Nationalmuseum and the Nasjonalmuseet, in Oslo.)

Among the more than 175 objects on display are an 1892 rifle from the Danish company Krag-Jørgensen, which supplied these guns to the U.S. army; examples of rosemaling, or Norwegian decorative folk painting, introduced to America in the 1930s by Per Lysne, an immigrant to Wisconsin; Finnish Marimekko textiles and clothing, whose simple shapes and bold patterns seemed shocking when they arrived in the U.S. in 1959; children’s toys, like those made by Denmark’s LEGO, which started exporting them to the U.S. in 1961 and is still the world’s top toy manufacturer; and many ergonomic objects, including a pair of scissors made by the Finnish company Fiskars, which developed their signature orange grip in 1967.

Americans, it seems, have long appreciated the earthier, homier aspects of Scandinavian design, especially in times of turmoil — a recent example is the embrace of the centuries-old Danish concept of hygge, the cultivation of simplicity, warmth and coziness. But it was in the postwar era that American tastemakers really sold the citizenry on the “Scandinavian dream,” suggesting that, like us, the inhabitants of the Nordic nations valued home, hearth, family and good craftsmanship and design, as well as democracy.

American interest in Scandinavian culture was ignited soon after the Civil War by Sweden’s exhibit at the United States’ first world’s fair, Philadelphia’s 1876 Centennial International Exposition. The display of wax mannequins of peasants and a model modern schoolhouse was so admired that New York City snapped it up for Central Park (where it’s now the Swedish Cottage Marionette Theater). In the 1920s and ’30s, Scandinavian objects became associated with refinement, and exclusive boutiques began to sell Georg Jensen silver, Orrefors glass and Bruno Mathsson’s wood and webbed-fabric or -leather chairs, extolled for “luxurious ease.” But even then, it was their handcraftsmanship that won plaudits.

The show’s most fascinating aspect, however, relates to mid-century design — including objects like Arne Jacobsen’s Egg chair, Alvar Aalto’s undulating Savoy vase and Tapio Wirkkala’s leaf-shaped birch-laminate tray — which took off in the States after the Second World War, when Scandinavia’s simple, curvilinear wooden furniture, home goods and textiles suddenly seemed the perfect foil for glass-and-steel skyscrapers.

As Obniski (now curator of design at Atlanta’s High Museum of Art) writes in the catalogue, the work was promoted with adjectives like honest, organic and handcrafted — although some was mass-produced — and “sold to American consumers by evoking a constructed ‘Scandinavian dream’ that paralleled the mythic ‘American dream.’ ”

One of the chief promoters was Elizabeth Gordon, editor of House Beautiful. Gordon became enraptured by Scandinavian design in the early 1950s and featured it heavily, starting with a 16-page spread in 1951. “Why are [Scandinavian] home furnishings so well designed and so full of meaning for us?” she wrote three years later. “Because they are so well designed and so meaningful for the Scandinavians themselves. Aimed at Scandinavian home life, their designs have a natural beauty and usefulness for our own, for we are both deeply democratic people.”

Her point about democracy had already been underscored by the design of the United Nations headquarters, in New York, where three Nordic nations, eager to ally themselves with the West during the cold war, had contributed funds and architects for its three largest meeting rooms.

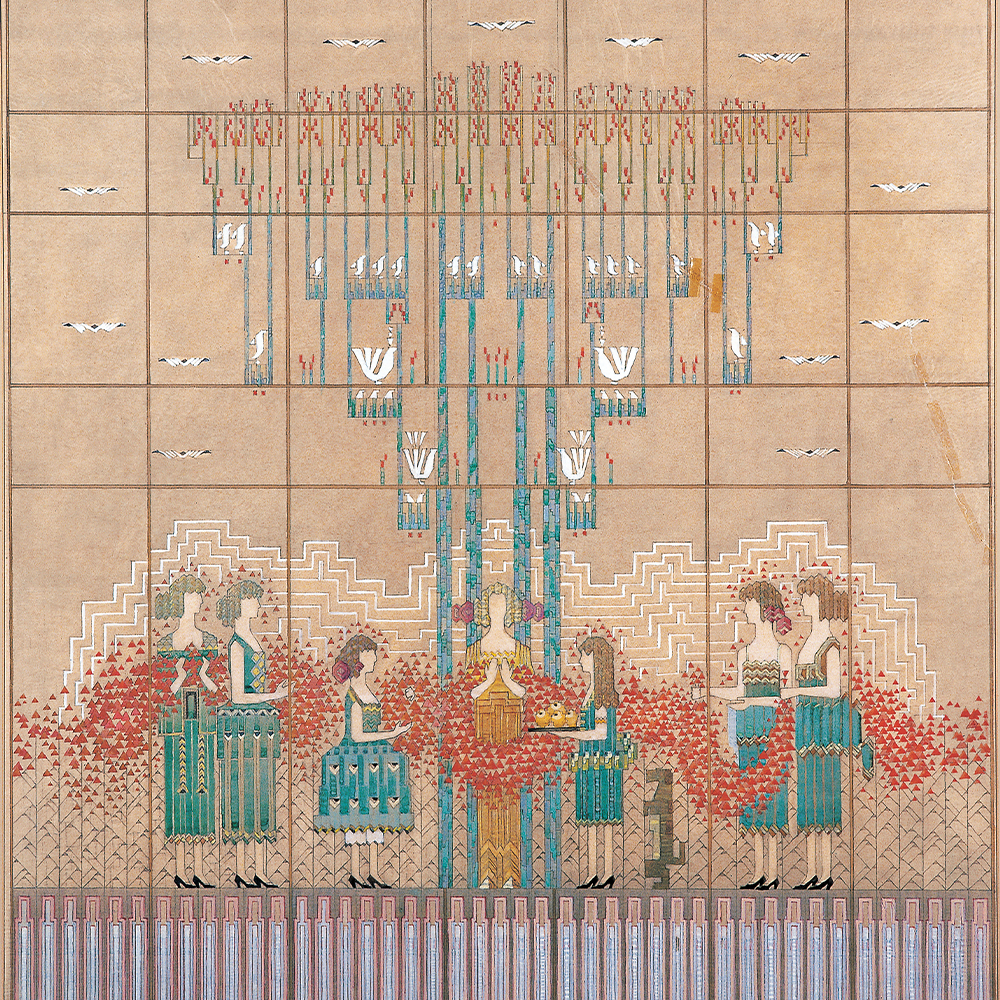

Denmark’s Finn Juhl created the horseshoe-shaped Trusteeship Council Chamber; Sven Markelius, of Sweden, designed the Economic and Social Affairs Council Chamber, hung with a Marianne Richter tapestry; and the Norwegian architect Arnstein Arneberg handled the Security Council Chamber. (Finland wasn’t yet in the UN. Having been invaded by the Soviet Union in 1939, it initially fought alongside the Axis.)

It was Gordon who pushed for the first major touring exhibition, “Design in Scandinavia,” which opened at the Brooklyn Museum in 1954 and traveled over the course of three years to 24 museums in the U.S. and Canada, presenting the material as the product of a regional culture that, unlike swiftly modernizing America, was deeply in touch with itself.

The show comprised “the arts and crafts of four mature, happily individualized nations,” read its press release, displaying “infinite varieties of personal expression and dozens of highly original solutions to the problems of making beautiful the surroundings for life today.” Gotthard Johansson, the president of Svenska Slöjdföreningen (the Swedish Arts and Crafts Society), wrote in the catalogue: “The four countries concerned belong to the sphere of Western culture. The design of the day is created for the people of to-day, people who live under conditions which are essentially much the same as those of the average American.”

During its tour, the exhibition drew 660,000 viewers, and it was accompanied in each location by films, lectures and local merchandising tie-ins. Its success sparked more such efforts, many initiated by the Nordic countries themselves, like the Scandinavian Design Cavalcade, a series of exhibitions, tours and store displays throughout the region, begun in 1955, which encouraged American tourists to visit.

“The Arts of Denmark: Viking to Modern” opened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1960 and traveled to the Art Institute of Chicago and the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery. In his forward to that catalogue, Viggo Kampmann, Denmark’s prime minister, once again expounded on the countries’ common values and their shared belief in democracy. “In all matters we Danes have the freedom of speech,” he wrote. “Today Denmark, with her sister nations throughout the North, raises her voice for the cause of liberty, tolerance and cooperation.” (If Americans wanted to buy some Danish furniture, it probably wouldn’t hurt the cause of liberty, either.)

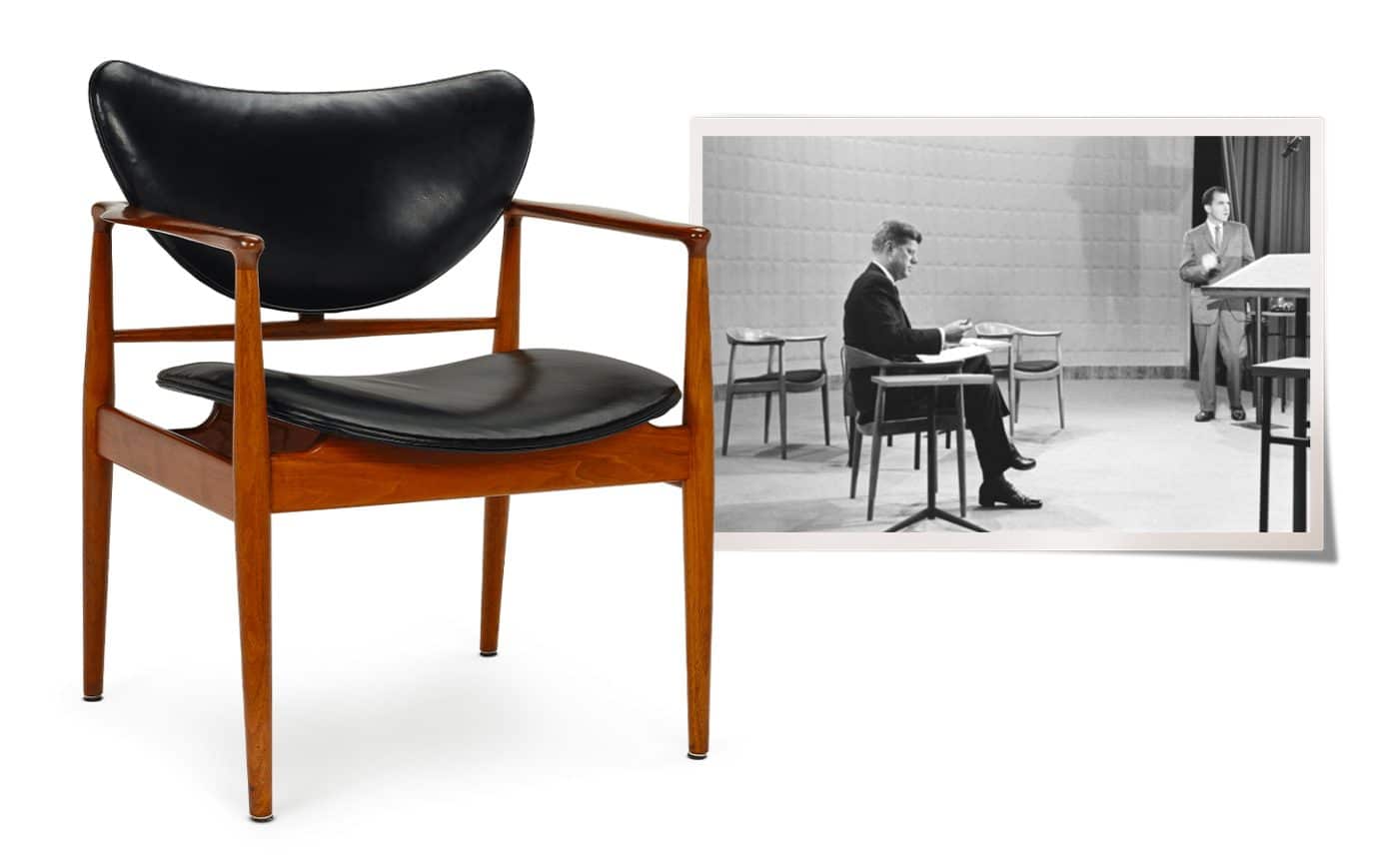

The spin reached its apogee that same year at the first televised presidential debate. John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon faced off against each other seated in a pair of Hans Wegner Round chairs (there’s one in the LACMA show), making Scandinavian furniture still more desirable.

Scandinavian design of a less hand-crafted sort enjoyed a major success in 1963, the year after the Cuban Missile Crisis, when Kennedy was photographed in the Oval Office with a troll doll, the creation of Danish woodcarver Thomas Dam, who switched to plastic to satisfy demand at home. After Kennedy was pictured with the grimacing gnome, rebranded by Dam as a Good Luck Troll, it sold like the proverbial hotcakes.

The doll didn’t exactly bring Kennedy good luck. And after his assassination, faith in American democracy eroded so swiftly during the Vietnam and Nixon years that it fell out of fashion as a marketing gambit. Perhaps that’s one reason why Scandinavian mid-century design became less popular in the 1980s. But today, the lingering sense that it embodies democracy, peace and neutrality may be contributing to its resurgence, which has been going strong for several decades now. Of course, the style has come to seem timeless. And as the curators write in the catalogue, the full panoply of Scandinavian aesthetics is truly “an integral part of what we now think of as ‘American design.’ ”