May 5, 2019At Designmuseum Danmark, the permanent exhibition “The Danish Chair: An International Affair,” and an accompanying book, explore the influence of historical pieces from other cultures on iconic Danish design. Top: The works displayed include the Ox chair by legendary designer Hans J. Wegner. Photos by Pernille Klemp

In Western design history the chair has generally been regarded as the ultimate design object, the designer’s touchstone,” Christian Holmsted Olesen, the head of exhibitions and collections at Copenhagen’s Designmuseum Danmark, writes in the introduction to the book The Danish Chair: An International Affair, released last month by Strandberg Publishing.

The fascination these “simple body-holders” exercise, he suggests, can be understood by referring to something the mid-century Danish designer Hans J. Wegner once said: “The chair is the piece of furniture that is closest to human beings.”

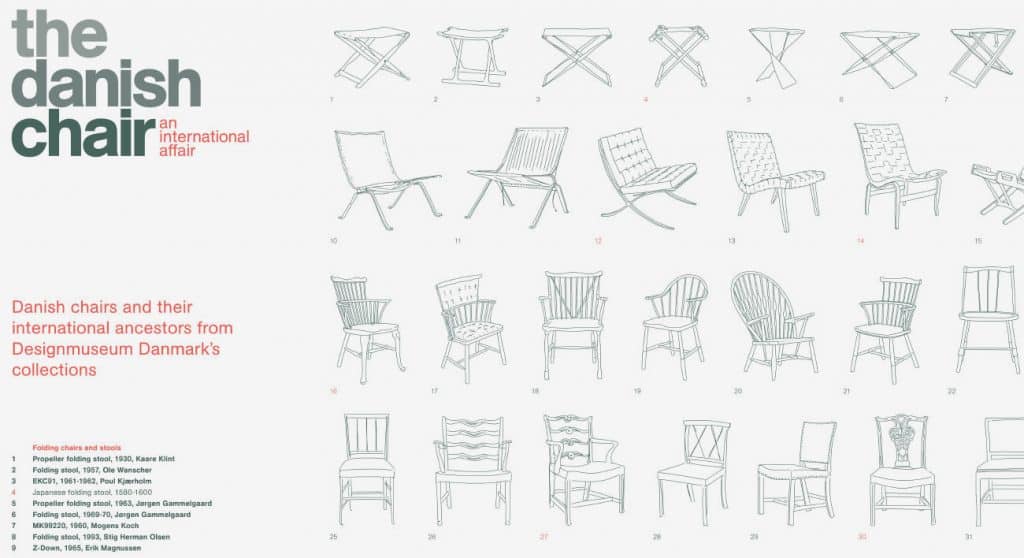

Since it was established, in 1890, the Designmuseum has collected about a thousand of these touchstones from Denmark and around the world. In 2016, he selected 113 for a permanent exhibition with the same name as the book. They’re displayed in a Wunderkammer-like installation — created by the Copenhagen furniture designer Boris Berlin — arranged on three levels in a single long gallery that suggests a barrel-vaulted tunnel, each in its own separate case, like a sculpture.

The exhibit includes mid-century modernist icons like Wegner’s 1949 Round chair, Arne Jacobson‘s 1952 Ant chair and Verner Panton’s 1960 Panton chair, as well as pieces by historical precursors like Kaare Klint, known as the father of Danish furniture design. Also on view are chairs from other countries and eras, such as a 16th-century Japanese folding stool, a Shaker rocker, Michael Thonet’s 1859 No. 14 bentwood bistro chair and Eero Saarinen’s Tulip chair. The pieces are grouped by construction type, such as shell and Windsor, suggesting the archetype that links certain styles throughout history.

Left: Verner Panton’s Panton chair. Right: Arne Jacobson’s Ant chair

The installation has been extremely popular with visitors and appears frequently in Instagram posts of the museum. Buoyed in part by this interest, along with the growing appeal of Danish design, museum attendance has soared from just over 63,000 in 2011 to nearly 280,000 in 2018.

The book, a handsome rectangular volume, is organized roughly like the show, with one chair per spread, showing how they relate to each other and the evolution of Danish design. “No other design culture is as thoroughly founded in the study of types and forms from other ages and cultures,” Holmsted Olesen writes in the forward, “which may seem paradoxical, since Danish design is simultaneously regarded as one of the most unambiguously national styles and brands in design history.”

He recently spoke with Introspective about the exhibition and the book, as well as the history and future of Danish design.

Copenhagen furniture designer Boris Berlin designed the exhibition’s tunnel-like display of chairs, which are arranged on three levels, with each piece in a separate case. Photo by Pernille Klemp

How did the show come about?

Danish design started in the nineteen fifties, but everybody is interested in it again. We have a lot of researchers and visitors coming to the museum and asking to see all the hidden furniture in the storeroom, especially the chair collection. So I thought, “Why don’t we just show the chairs in public?”

How did the concept for the exhibition evolve?

My idea was to show that Danish design is extremely influenced by historical furniture and furniture from other cultures. That’s actually its most important characteristic: It’s not so much about innovation, it’s more about refining existing ideas and making them work in our own time.

The exhibition includes a range of chairs that influenced Danish design, like a Shaker rocker and Michael Thonet’s 1859 No. 14 bentwood bistro chair. Photo by Pernille Klemp

That explains why there are so many chairs in the museum that aren’t Danish.

I’d say ninety-five percent of all our collections are foreign, because, like the Victoria & Albert in London, we started as a museum of arts and crafts, and then we collected internationally to be an inspiration source for Danish designers. No nation in the world has been as inspired by design from other nations as Denmark.

How does Danish modernism differ from European modernism?

European modernism, like the Bauhaus, was much more about inventing something new. In Denmark, it was completely the opposite: You should study the history and improve on it. That’s because Denmark wasn’t industrialized until after the Second World War. On one side, Danish design is about being functional, fit for the purpose, like modernism. But on the other, it’s very traditional, with craft and historical forms. It’s this strange mix.

And it’s only because America fell in love with that wonderful craft that still existed in Denmark after the war that Danish design is world famous. Without America, Danish design wouldn’t be a brand.

How did that happen?

American journalists came to the 1949 Cabinetmakers’ Guild Exhibition, which was held annually at the museum, and wrote about this furniture. The avant-garde around MoMA and New York fell in love with it. It fit very well with modernist architecture. Denmark was quick to understand the possibilities. It started making big traveling exhibits to the U.S., together with other Scandinavian countries, with all this storytelling about the farming culture, this fine craft tradition and democratic society.

Then-senator and future president John F. Kennedy was seated in Wegner’s Round chair when he sparred with Richard Nixon (whose shadow is visible on the wall) in the first televised American presidential debate, in Chicago on September 25, 1960. Photo by CBS Photo Archive/Getty Images

The exhibition and the book both include the famous photo of John F. Kennedy sitting in a Hans Wegner Round chair during his 1960 debate with Richard Nixon.

By 1960, America was a big export market for Denmark, and that picture meant so much for the export of Danish design. There was a story that Kennedy had chosen the chair because he had a bad back. It was even said he liked it because he liked Danish democracy. And of course, Kennedy was very popular in Europe. Nixon was sitting in the same chair, but they never showed the picture because he lost the election.

Wegner’s chair was discovered in the 1949 Guild Exhibition. Why did it excite journalists so much?

They liked that it was modern, simple and wood and had organic forms but also craft and tradition. Wegner couldn’t understand it. He said himself, “It’s just a simple chair. What’s new about it? It could have been made two hundred years ago!” He had done something in plywood — he was inspired by Charles Eames — but his cabinetmaker was furious and said, “Plywood is for industry. You have to make a real cabinetmaker chair.” He made it in forty-eight hours before the exhibition opened.

Poul Kjærholm‘s wicker and chromed-steel EKC22 chair, 1955–57. Photo by Pernille Klemp

What did he design next?

After 1949, when the Americans suddenly said, “Can we have four hundred of these chairs?” Wegner had to design something suited for semi-industrial production. The Wishbone chair is a good example of that style. It’s half industrial and half craft. Many people think it’s a real cabinetmaker chair, but many of the parts are made by machines.

How is the Danish design influence felt today?

Star designers like Philippe Starck, Naoto Fukasawa and Konstantin Grcic, along with many others, are looking at Danish design. The British designer Jasper Morrison is crazy about it. In 2011, he made an exhibition here with our collection, “Danish Design — I Like It!” And the Scandinavian or Danish modern style is no longer Danish but international. The obsession with details, natural surfaces, historical forms and types has become a style. It’s no longer Danish only.