September 22, 2024We’ve come a long way since 1969, when “Objects: USA” debuted at the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C. The monumental exhibition traveled to more than 30 museums worldwide, dramatically elevating the American studio craft movement and the reputations of its practitioners, including George Nakashima, Wendell Castle, Sheila Hicks and Dale Chihuly.

Four years ago, the New York gallery R & Company took a look back at that seminal show with “Objects: USA 2020,” pairing 50 pieces from the original catalogue with 50 by contemporary makers. The latest iteration, “Objects: USA 2024,” which opened September 6 at R & Company’s impressive White Street space and remains on view through January 10, 2025, is a rich lode of present-day talent and innovation, very much of this moment. The gallery sees it as the first in what will be a series of triennial surveys.

“Objects: USA 2024” is a “study of now,” says Zesty Meyers, who cofounded R & Company with Evan Snyderman nearly three decades ago. Together, the two have evolved the gallery from a Williamsburg, Brooklyn, store selling vintage modern furniture to its current key position in the vanguard of collectible design. “It’s cultural anthropology,” Meyers says of the exhibition. “The makers in this show are taking the culture and pushing it forward. So many people from the original ‘Objects: USA’ are still very influential. I’m hoping these artists will be superstars in fifty years.”

The 55 U.S.-based talents represented by the nearly 100 works on view are explorers in a brave new world of object making. Although handmade designs have long been R & Company’s bailiwick, not everything in the current exhibition is strictly handcrafted. Nevertheless, “hands are vital,” says Kellie Riggs, who guest curated the collection with Angelik Vizcarrondo-Laboy, another independent curator who, like Riggs, has done stints at New York’s Museum of Arts and Design (MAD), among other respected institutions. “Nothing in this show could be what it is without the hand, even if technology were also used.”

Meyers concurs, adding that although all the work feels startlingly new and original, inspiration didn’t spring from nowhere. “If you asked the artists in the show, they would likely reference earlier artists as inspiration. That gives them the freedom to take chances. Without the past, we cannot create the future.”

Groundbreaking though it was, the 1969 show organized the works according to comfortingly familiar categories: clay, wood, fiber, glass and so on. This time around, they are grouped not by material but by something less tangible: meaning. Riggs and Vizcarrondo-Laboy corralled the selected pieces into what they call “archetypes of objecthood.” “First you observe a thing, then you name it,” Riggs says. “We didn’t just shove artists into groups that didn’t make sense. We observed what was at the core of each person’s practice, why they make what they make.”

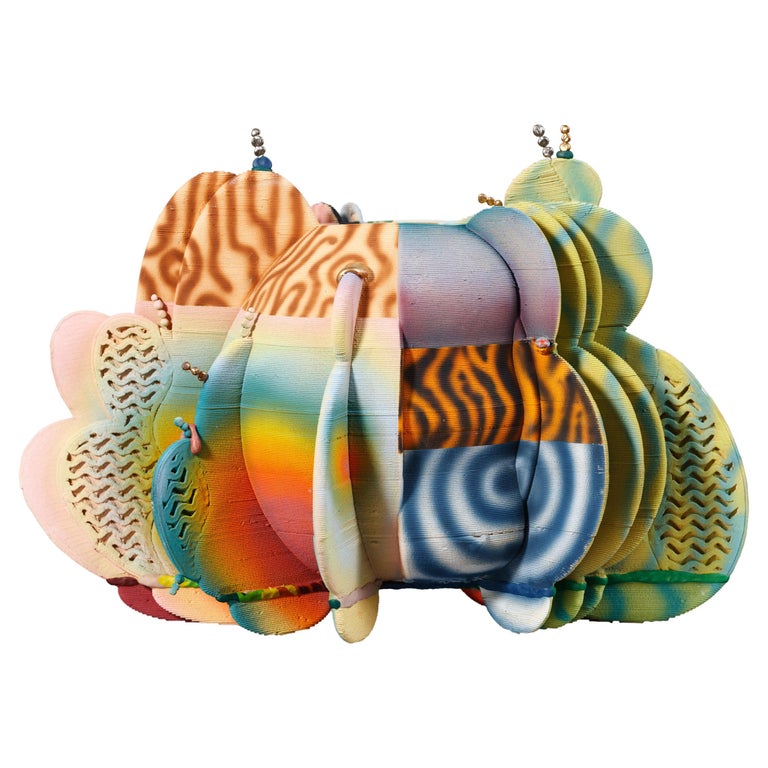

The artists are sorted into seven subsets: Truthsayers honor the nature of a single material; Betatesters are tech-forward innovators in a post-digital landscape; Doomsdayers are time travelers who create otherworldly objects fit for the future; Insiders gleefully twist our relationship with domesticity; Mediators focus on the interaction among human, object and environment; Codebreakers view objects as conceptual brainteasers; and Keepers are storytellers in the realms of history and memory.

If the show were held in a museum and not a gallery, the walls would likely be pure white. Here, seven lush colors, each representing an archetype, envelop visitors as they take in the whole exhibition, wending their way from the soaring spaces on the ground floor down the marble staircase and through the rooms on the two lower levels.

The entry hall, with multicolored walls, includes works from each of the seven categories. By way of introduction, such pieces as the elemental carved-wood chairs of Minjae Kim and the colossal ceramic pots of Pueblo elder Lonnie Vigil, who employs traditional hand-coiling techniques with a modernist sensibility, are toward the front, silhouetted against walls of pink. Classed as Truthsayers, “they’re artists who care about materiality in a simple, sincere way,” Riggs says. “We wanted people to remember the ABCs.”

The exhibition continues on the same level with Betatesters (yellow), Doomsdayers (light blue) and Insiders (purple). The floor below, where the gallery’s office and library are located, displays just two works, both by Insiders: Anne Libby’s gleaming aluminum wall sculpture These Days, which resembles nothing so much as an attenuated venetian blind, and the earthenware-and-porcelain Floating Ground floor light of Linda Lopez. Another flight down, and you’re surrounded by the imaginings of Mediators (green), Codebreakers (orange) and Keepers (turquoise).

Captivating works lurk in every corner, tucked into side rooms or suspended from the ceiling. Brian Oakes’s Vessel 4 is a glittering, seven-foot-wide, chandelier-like assemblage of showstopping beauty, made of circuit boards, electronic components, audio cables, chains and miscellaneous hardware. Oakes is a Doomsdayer, their piece’s abundance of electronics reminding us, according to the show’s catalogue, of “global dependency and potential e-waste.”

Nothing is merely pretty in the Doomsdayer room, though many objects indeed are — like the dazzling trompe l’oeil printed-aluminum Sluggard Waker floor light by Ryan Decker and design duo Chen Chen and Kai Williams’s liquid-nitrate-infused mirror, studded with sliced mineral specimens in a process they call “geological archiving.”

Vincent Pocsik, a Betatester, uses video-game software to design furniture and lighting resembling grotesque humanoid figures, then painstakingly hand-finishes them. His floor lamp of carved maple dyed blue, Standing with One Oxford, is an arresting case in point.

Misha Kahn, a Codebreaker in the exhibition lexicon, is represented by his fantastical free-form Windswept table of stainless steel, its cratered top filled with slumped glass. In the same category is Richard Chavez, whose puzzle-like inlaid jewelry in sterling Silver, jade and coral arises out of the Native American design tradition and his own architecture background.

Mundane household items like sneakers and bathroom tiles are the stuff of Francesca DiMattio’s towering glazed-porcelain constructions, as heavily ornamented as rococo. Her focus on the domestic realm makes her an Insider, along with Hugh Hayden, whose woven-rattan basketball hoop/water jug, titled Waterboy, joins African craft tradition with African-American sport and pastime.

Dee Clements, a Mediator, makes a feminist statement with Grotesque Flowers: On the Pressure to Be Seen, a vibrant, oversize piece of basketwork that mimics the curves and folds of a woman’s body. Well-known ceramist Roberto Lugo falls into the Keeper category with his Century of Education vase. It’s part of his “Century Vase” series of glazed stoneware whose forms are reminiscent of historic wares but whose lustrous painted decoration features portraits of the artist’s heroes, from W.E.B. Dubois to Kobe Bryant.

Meyers has far-reaching ambitions for “Objects: USA 2024.” “The overarching goal is to get people to stop and think, and to dream, from the twenty-year-old in Ohio to the eighty-year-old in New Mexico, and to see that there’s greatness happening here,” he says. “If they can’t afford the work, we want them to at least have the catalogue.”