June 6, 2021Well known as top dealers in collectible design, Evan Snyderman and Zesty Meyers have always been, at heart, makers. In the 1990s, before they founded their New York City gallery, R & Company, they were glass artists, creating their own sculptural works while traveling around staging offbeat glassmaking performances as members of an experimental collective known as the B Team.

“We called ourselves the B Team because we knew the A Team” — a.k.a. the insular glassmaking establishment — “was never going to accept us,” says Meyers. “At the same time, craft had sort of became a dirty word. But how do you work in any medium without knowing your craft? The B Team’s goal was to bridge the boundaries between craft and fine art because we didn’t see a difference.”

That fundamental belief in the power of skilled handwork, especially when paired with robust conceptual ideas and an awareness of history, has been something of a mission statement for R & Company since Meyers and Snyderman founded the gallery (originally R 20th Century), in 1997. It’s also very much central to their current show, “Objects: USA 2020,” which occupies all three floors of the gallery’s White Street space through the end of July.

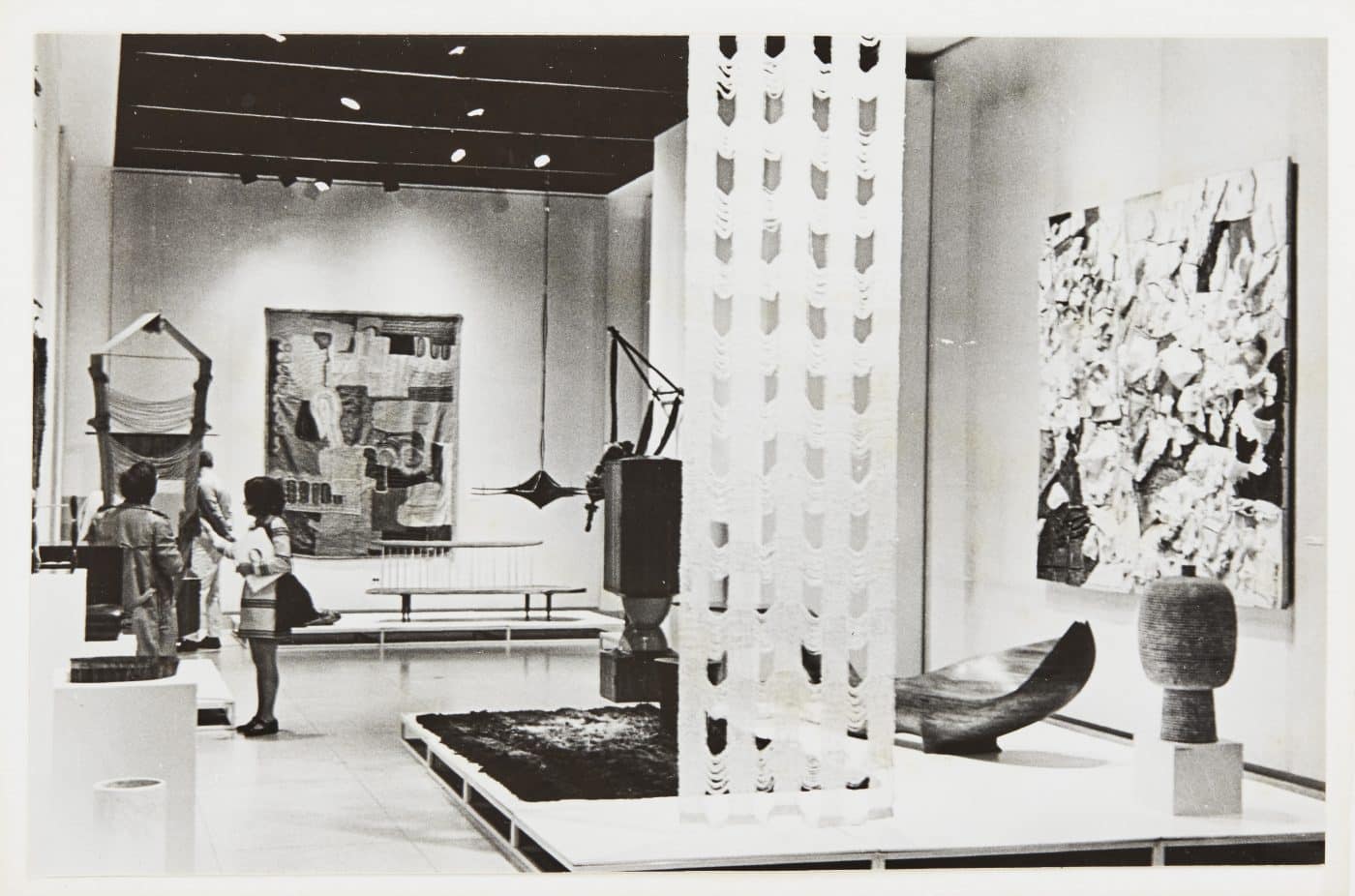

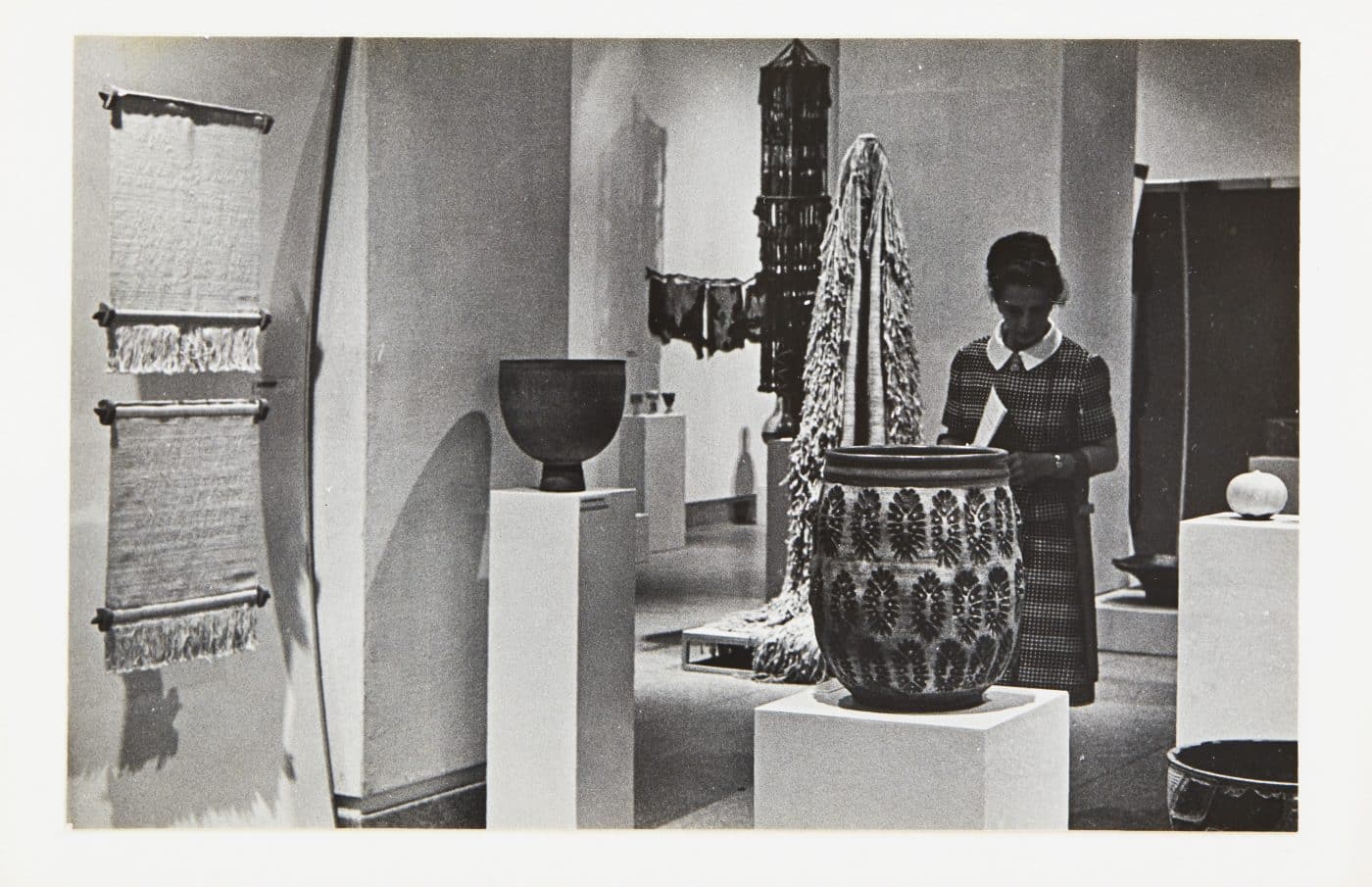

Several years in the making, the show was conceived as a sequel to the landmark exhibition “Objects: USA,” which debuted in October 1969 at the Smithsonian’s National Collection of Fine Art, in Washington, D.C., and featured some 250 artists from across the country working in a variety of craft disciplines. Organized by enterprising dealer Lee Nordness and Paul J. Smith, then director of the Museum of Contemporary Crafts (now the Museum of Arts & Design), the sprawling survey aimed to highlight the diverse achievements of the ceramists, woodworkers, glassmakers, metalworkers, jewelry designers and textile artists driving postwar America’s burgeoning studio craft movement.

The exhibition traveled to 22 museums in the U.S. and another 11 in Europe and was seen by more than half a million people, giving American craft artists pivotal — and, for some, career-changing — exposure. The accompanying catalogue became an essential reference for curators, auction specialists and dealers, not least Meyers and Snyderman. “A well-worn copy sat on my parents’ coffee table most of my childhood,” says Snyderman, whose mother founded the Works Gallery in Philadelphia in 1965. “We probably visited half the people in the 1969 show, which elevated an entire generation of artists.”

Some 50 years on (and after a COVID-prompted delay), Snyderman and Meyers are presenting a cross-generational twist on the original concept, pairing roughly 50 artists from the 1969 exhibition — among them Anni Albers, J.B. Blunk, Sheila Hicks, Sam Maloof, Peter Voulkos and Wendell Castle (who enjoyed a late-career resurgence before his death, in 2018, thanks in no small part to Meyers and Snyderman) — with an equal number of younger practitioners working today.

Several of the 21st-century artists are among R & Company’s biggest stars. Rogan Gregory is represented by an otherworldly, amorphous gypsum light fixture, while Katie Stout is showing one of her wittily riotous ceramic Fruit Lady floor lamps, composed of sculptural ceramic vegetal components worthy of an Arcimboldo painting. And the Haas Brothers, provocateurs known for their wacky-chic, often animalistic furnishings, have contributed a Beast chair upholstered in Icelandic sheepskin.

Still, to better represent the diversity of contemporary makers — something the 1969 exhibition has been praised for — Meyers and Snyderman cast a wider net, borrowing works from 17 other galleries as well as private collections and foundations. “The selection of contemporary artists and designers needed to be diverse in both gender and race and capture a broad view of what is happening inside makers’ studios in America,” says Snyderman, who worked closely with the curatorial team, headed by Glenn Adamson, the writer, historian and former director of the Museum of Arts & Design. (Abby Bangser, founder of the Object & Thing fair, advised on the contemporary artists; R & Company museum relations director James Zemaitis assisted with the historical material.)

“The selection of contemporary artists and designers needed to be diverse in both gender and race,” says R & Company gallerist Evan Snyderman, to “capture a broad view of what is happening inside makers’ studios in America.”

Nigerian-born artist Ebitenyefa Baralaye contributed a stele-like terracotta slab with a graphic, almost abstract serpent in relief, suggesting a mystical ancient relic. Joyce Lin, an artist and designer of Taiwanese descent, is represented by her Skinned table, one of her deconstructions exploring the physical and ultimately unknowable historical layers of found furniture. (A 2017 graduate of the Brown/RISD Dual Degree Program, Lin is the youngest designer in the show.) Adejoke Tugbiyele, a queer Black artist and advocate, is showing a rhythmically twisting sculpture crafted from Zulu grass brooms known as umchayelo, evoking associations with female domestic work and cleansing rituals.

With only rare exceptions, the show’s contemporary pieces are from the past few years, while the older works are mostly from the period of the original exhibition, dating to the early 1960s and mid-’70s. All but about 10 percent of the works are for sale, with another 10 percent reserved for purchase by museums only. “We really tried to have as much as possible be for sale,” says Meyers. “We’re not a museum. People come here to appreciate things, but they also come to buy.”

The show’s installation, spearheaded by Snyderman, was particularly complex. He says he “must have gone through a hundred iterations of the layout before arriving at the final plan,” which revolves around a series of nonhierarchical vignettes that freely mix mediums and time periods. “It was key,” he explains, “that no pride of placement was given to the more blue-chip names.”

In one grouping, a cloud-like light fixture of azure-tinted glass disks made last year by Jeff Zimmerman hovers above a tongue-shaped Wendell Castle table in gel-coated orange plastic and a walnut wine rack with sensual Surrealist curves by Art Carpenter, both from the late ’60s. In another, a recent Liz Collins textile hanging, whose magenta zags and dripping fringe exude the energy of an Abstract Expressionist painting, serves as a backdrop for a classic 1966 George Nakashima Conoid slab bench and a trio of Jiha Moon’s recent ceramic vessels that riff on traditional forms and are embellished with playful pop-culture motifs.

Displayed throughout in vitrines and on shelves are smaller pieces, from Doyle Lane’s exquisitely glazed 1960s and ’70s weed pots to recent whimsical assemblages made with flocking by John Souter (“the next small-scale object maker genius,” according to Meyers) to glass sculptures that Richard Marquis created at Venini in 1969–70, when he became the first American to work alongside the masters at the storied Murano glassmaker.

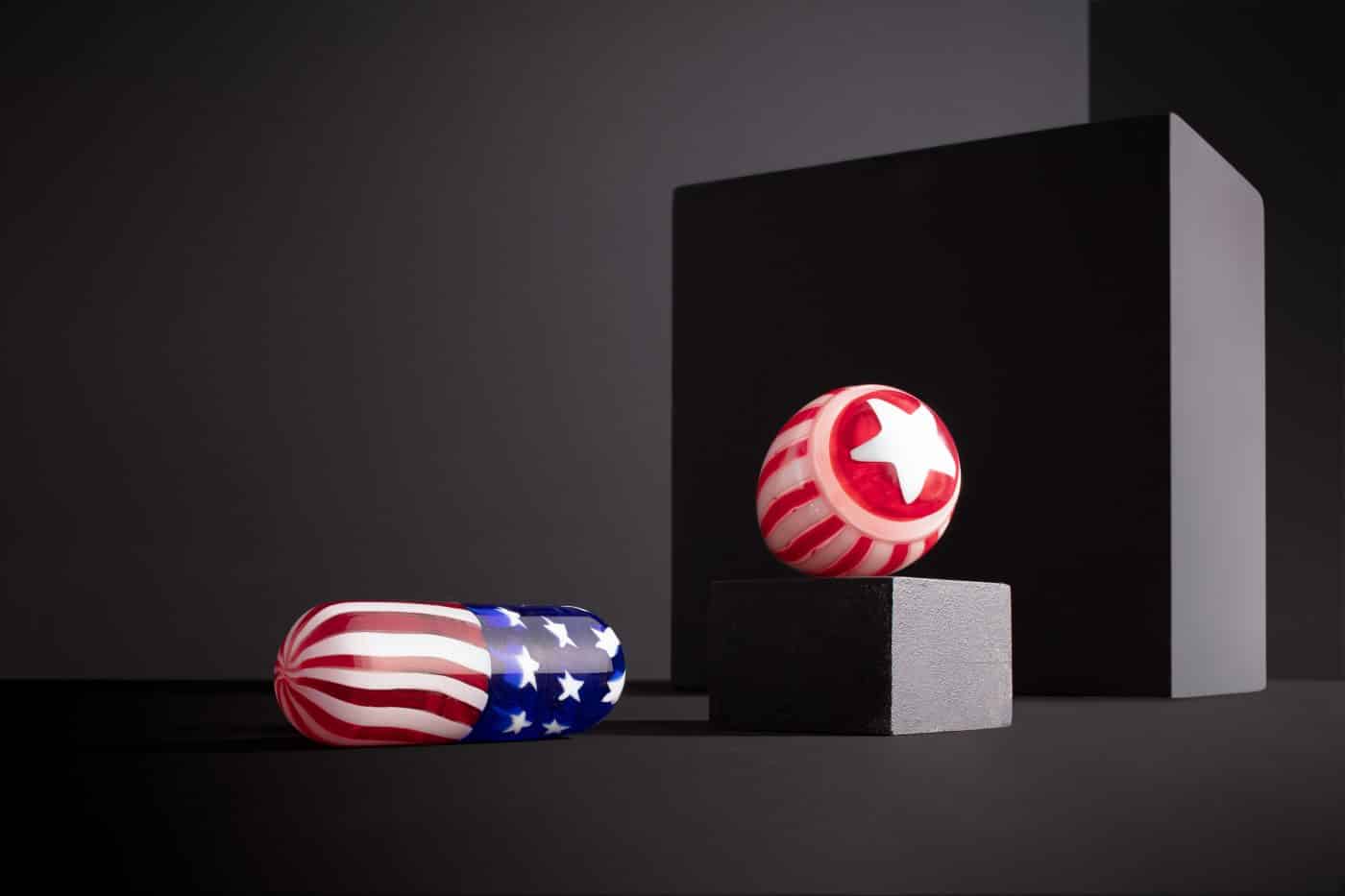

Especially memorable among the pieces by Marquis — credited with bringing to the U.S. traditional murrine techniques for creating lines and patterns in blown glass — is his Stars and Stripes acid capsule, which speaks to the forces that shaped the psychedelic ’60s: hippie culture and Woodstock, the Vietnam War, the civil rights movement and social unrest. “I dreamed of this object for years,” says Meyers, who had seen it in books and knew two versions belonged to museums. “It turns out he made four of them. I never expected that we would have one for sale. It’s a once-in-a-lifetime thing.”

Parallels can be drawn, of course, between the historic context, half a century ago, from which “Objects: USA” emerged and our own uneasy, politically divisive, COVID-plagued times. But the world is very different, including the sphere of object makers.

Today, the old boundaries that separated creative disciplines — glassmaker, ceramist, metalworker — have blurred. Studio practices are more fluid, artists are now apt to experiment with different processes and materials, and, as Adamson notes in his catalogue essay, “ ‘mixed media’ is the order of the day.”

Equally significant, cultural references are as diverse as the makers themselves. And technology has played a big role, exploding possibilities — of materials, of form, of scale — while also helping to democratize information and access.

And yet, despite all the changes since 1969, a common thread runs through the work at R & Company — what Myers calls “the hand.” There is, he explains, “something inherent in us that makes people want to express themselves with these techniques, these crafts.”

Even as our world continues its rush toward the digital and the virtual, the allure of handmade — and especially unique — objects remains strong. The reaction against the mass-produced and the disposable that propelled the postwar studio craft movement, Meyers argues, manifests today in a hunger for the meaning and authenticity of objects crafted with passion, skill and dedication.

Meyers and Snyderman’s goal is to celebrate the amazing range of creativity of makers in America, past and present, as widely as possible. Their hope is to have the show travel, as the original did, with the corporate sponsorship of the SC Johnson company (which also purchased all the works in the 1969 exhibition and later donated most to institutions, including 123 now in the collection of the Museum of Arts and Design). While efforts aimed at achieving this are still in the early stages, Meyers says “there’s been very, very strong interest.“

In the meantime, the duo has launched an initiative called WITH OUR HANDS, inviting makers around the country — whether industry professionals, students or weekend hobbyists — to share their stories in brief videos that are posted on the exhibition website and on the gallery’s social-media platforms. “Out of the three hundred and thirty million people in this country, how many are makers? It’s a really good question,” says Meyers. “It’s not about whether you sell your work. It’s about feeling that you need to do this and you have something to say.”

Exactly, in other words, how Meyers and Snyderman felt about staging this new show.