July 2, 2023Sometimes, it seems there are no truly fresh artistic discoveries, since collectors have gotten very good at scouring the landscape for talent and then snapping it up. Then, a show like “Antonio Petruccelli: Rediscovering a Modernist” comes along, and we realize that we have not seen it all yet.

The show, comprising 40 works, all original gouaches on board, is up through September 6 in a private, by-appointment space at Manhattan’s Helicline Fine Art, and the works are available on 1stDibs.

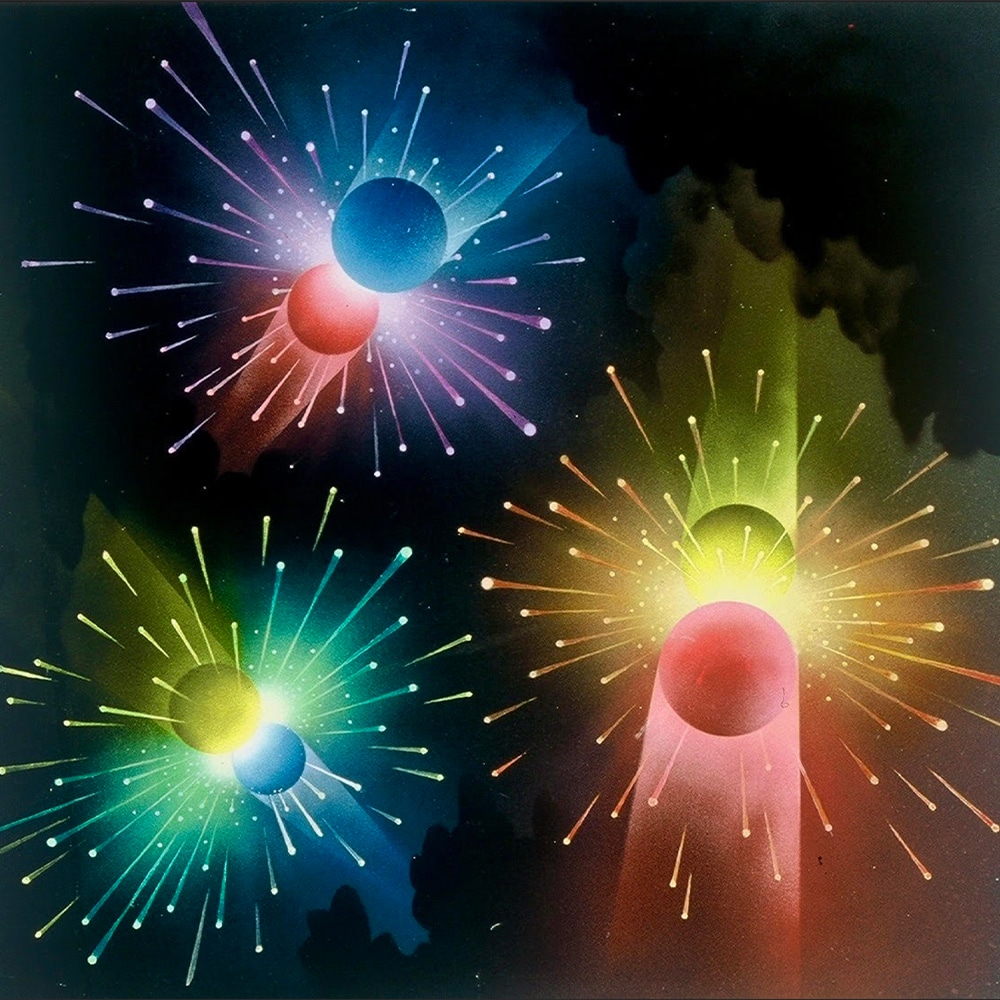

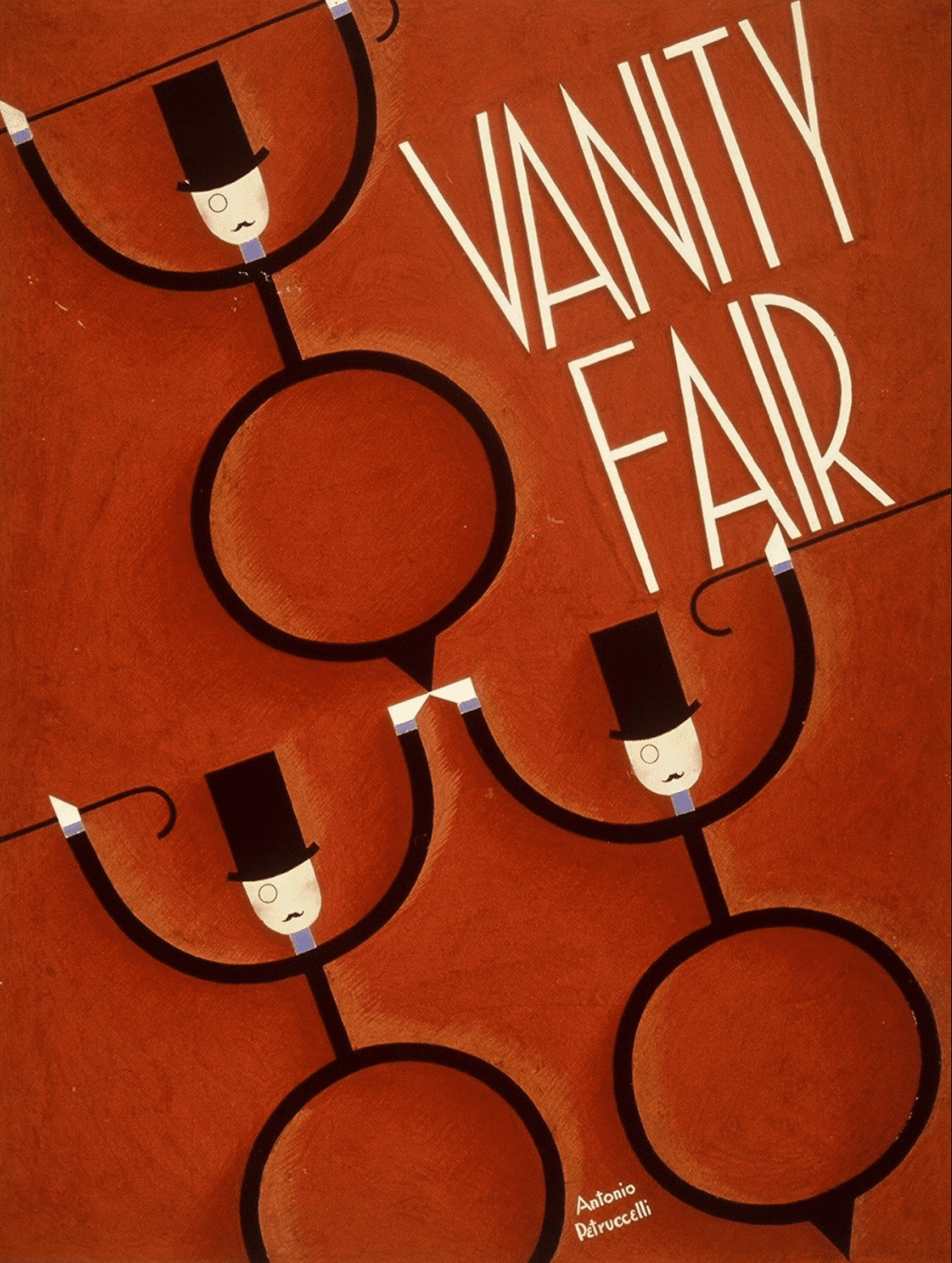

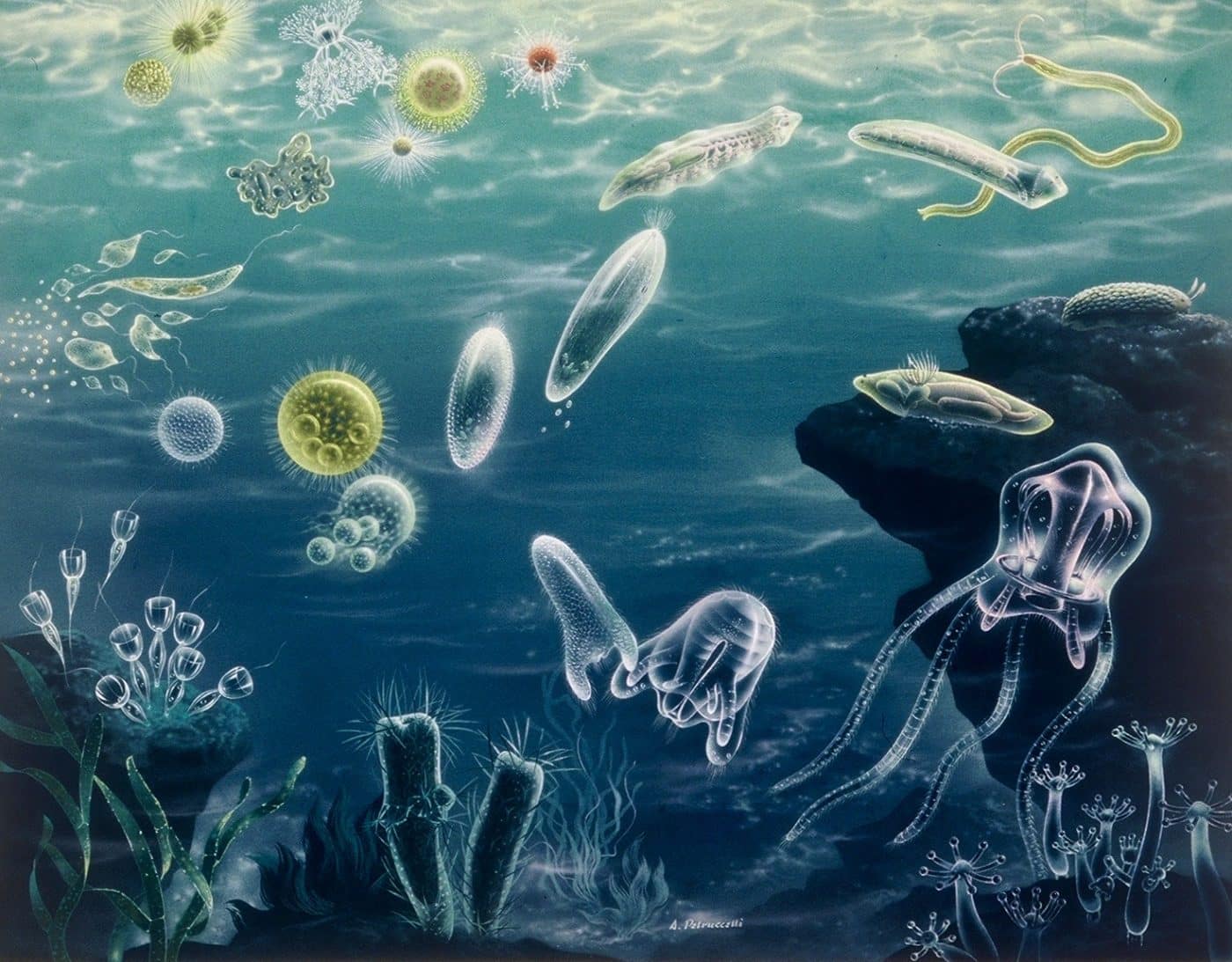

It introduces us to Antonio Petruccelli (1907–94), a wildly talented American artist who did illustrations, and frequently cover art, for Fortune, Vanity Fair, Life and the New Yorker, among other publications. His heyday was the 1930s to the 1960s, not coincidentally the heyday of magazines in the United States. The images are redolent of their era: Multiple scenes reference World War II and the scientific and technological advances of the day (including a detailed 1930s illustration of a nuclear warhead for The Lamp, the magazine of Standard Oil).

But somehow, Petruccelli’s name is virtually unknown.

“I love his work,” says Lea Nickless, a curator at the Wolfsonian museum, part of Florida International University in Miami Beach. “He was a super-talented maker of highly stylized images.”

Indeed, Petruccelli is a great example of what you might call Mid-20th-Century Quirk, the same fertile soil that later produced, in a more surreal and overtly jokey mode, the great New Yorker illustrator Bruce McCall, who died this past May.

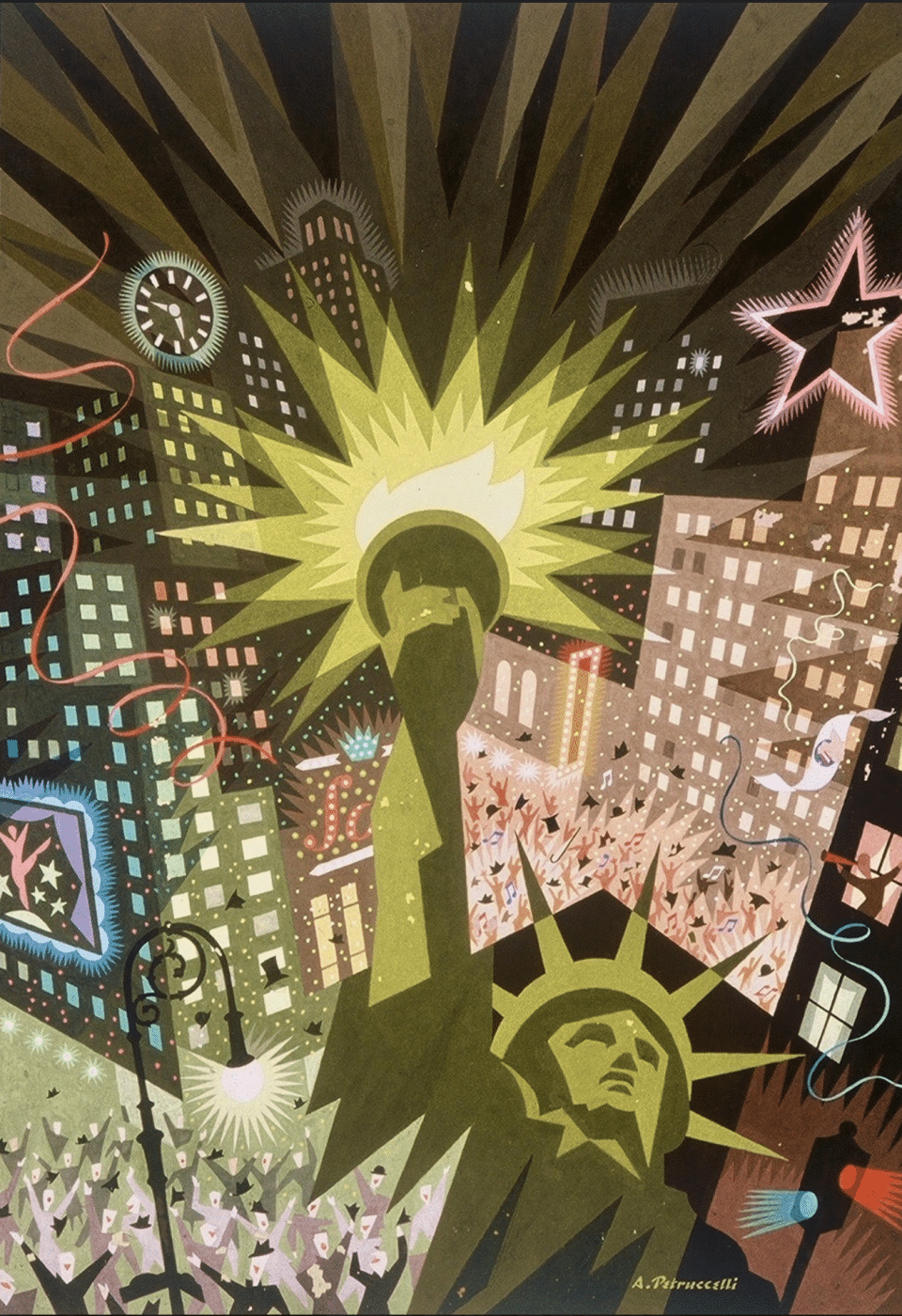

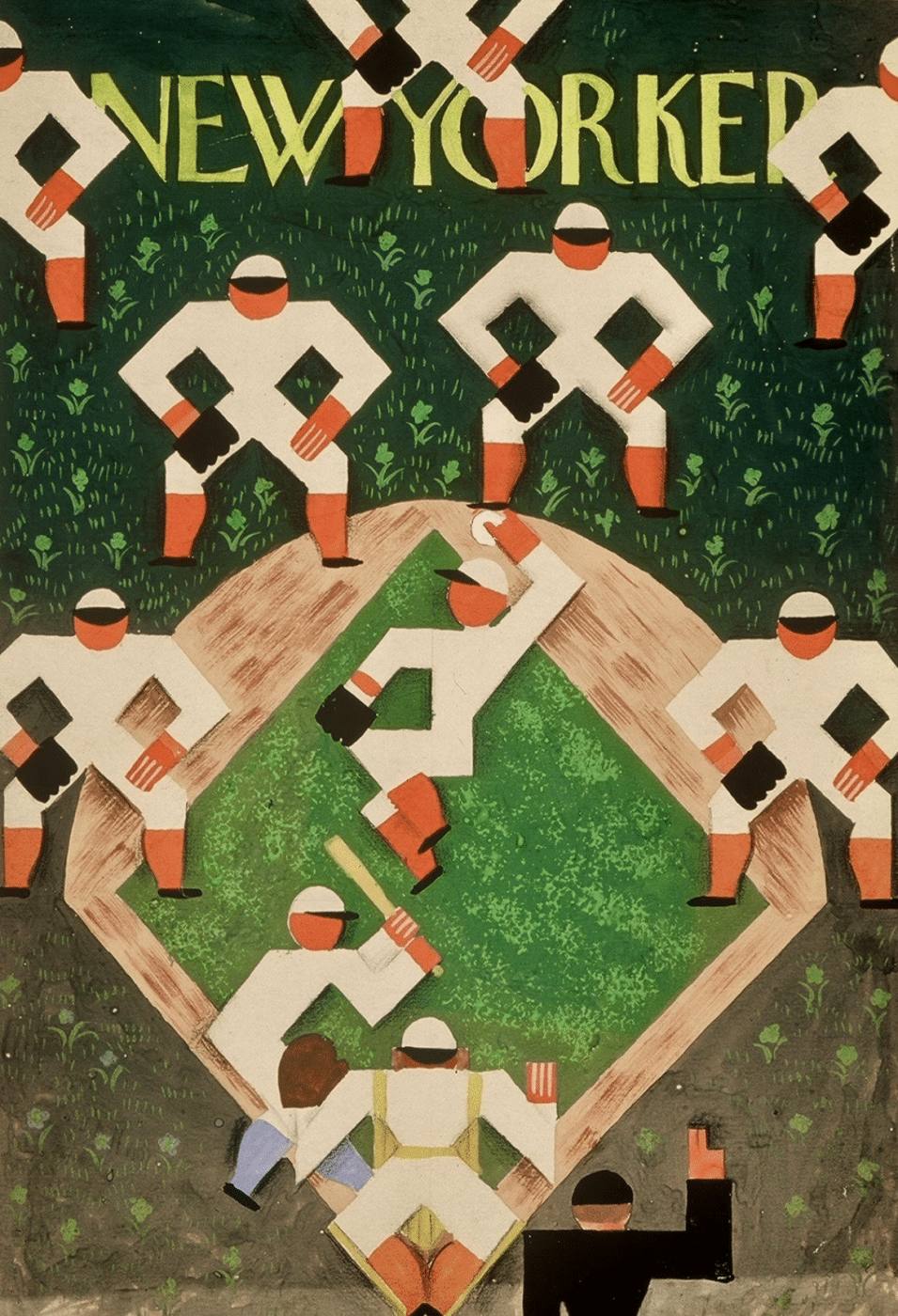

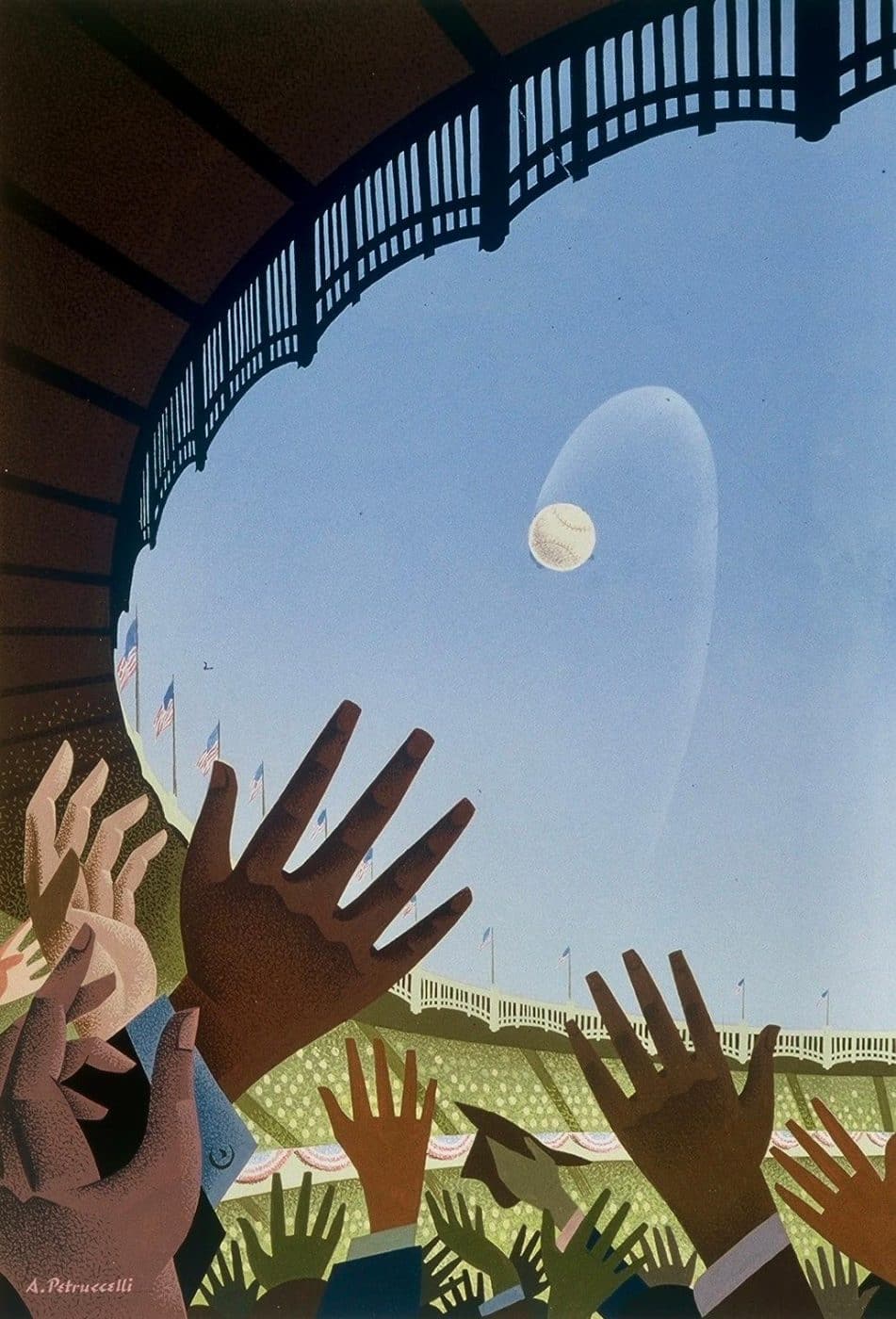

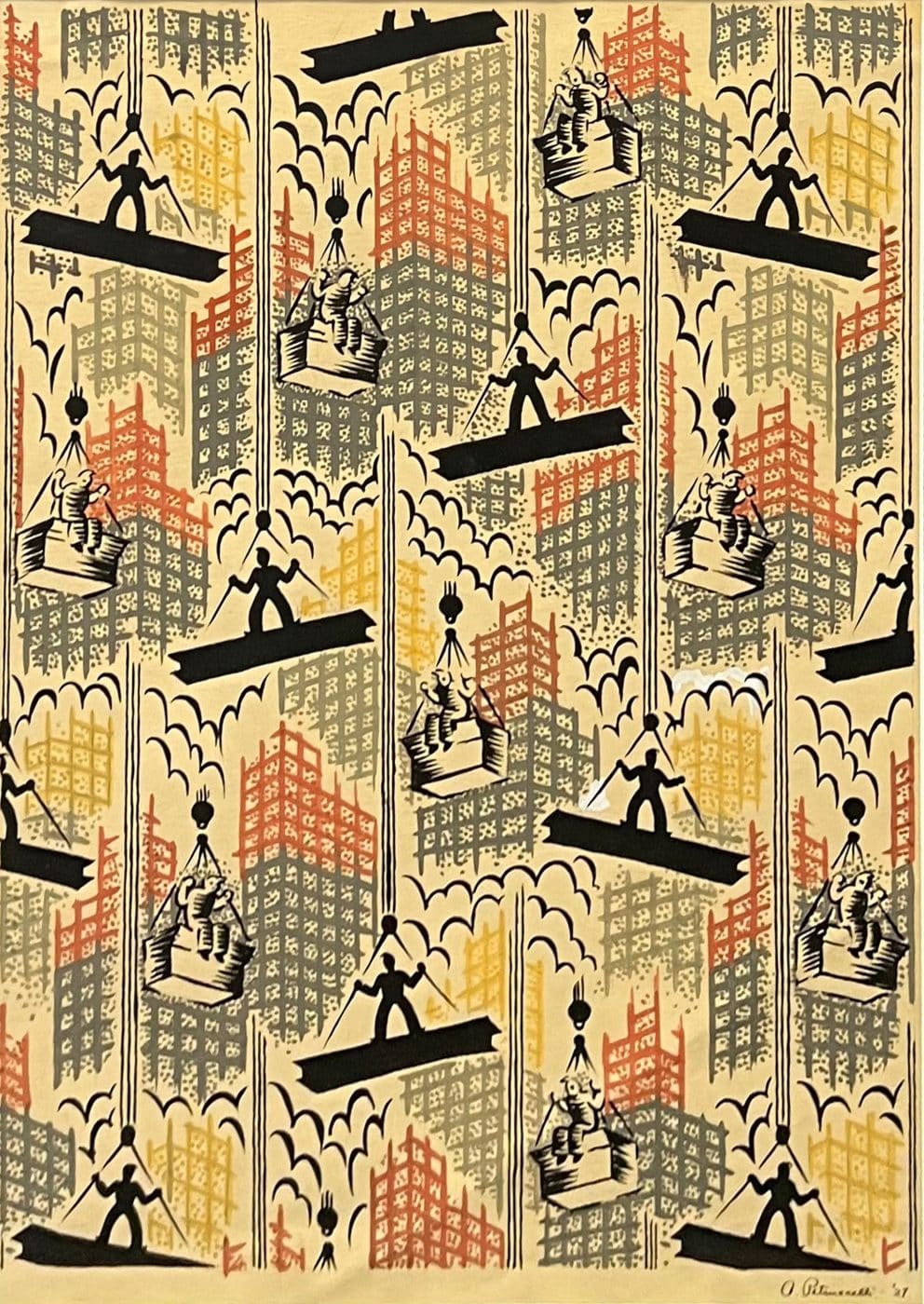

All of Petruccelli’s images take graphic risks, mixing whimsy with confident, strong lines. He had a knack for odd geometries. “It’s a reduction of elements to get to the core,” says Keith Sherman, Helicline’s cofounder.

In Play Ball, a 1939 cover proposal for the New Yorker, baseball players are reduced to whimsical, squat, proto-pixelated forms. In the sparer Military Tent City, a Fortune cover from May 1941, the image is simply a repetition of dun-colored pyramidal tents, arranged to suggest the vastness of the fight in World War II.

The compositional flair of the paintings is among the things that attracted Sherman when he first encountered Petruccelli’s art, a dozen years ago. “We went to a museum in New Jersey and saw his work,” says Sherman, a noted New York theater publicist, who founded Helicline with his husband, Roy Jeffrey Goldberg. “We had never heard of him.” They were smitten. “Our jaws hit the floor. It was stunning.”

Certainly, the duo was primed to be receptive to Petruccelli’s work. Helicline’s speciality is modernist American paintings, sculpture and works on paper, particularly those from the 1920s, ’30s and ’40s.

“We fell in love with the period when we got our first apartment, in a 1920s building,” Sherman says. “We went down to the Strand” — the famed Manhattan bookstore specializing in vintage volumes — “to see what homes looked like in the 1920s.”

Although they already knew a bit about Art Deco and Machine Age design, which clearly influenced Petuccelli’s style, they decided to steep themselves in the movements. As Sherman puts it, “It gave us a different perspective and gave us our taste.”

Petruccelli’s is an appealing underdog story, one that his sons and grandsons are working to make better known, now with the help of Sherman, who is representing the estate. The artist was born in Fort Lee, New Jersey, and raised in Manhattan’s Little Italy. “He was a true New Yorker,” says his eldest son, Mike Petruccelli, 89. “Grew up a Yankee fan and died a Yankee fan.”

Illustrating came early. “From middle school onwards, he was always making art,” says Mike. “It was a passion for him.” He attended a special New York high school for textile design and later practiced it as a profession.

He met his future wife, Toby, when they were both designing textiles for the same company. They moved to New Jersey and worked freelance from home long before that became a typical modus operandi. His textile training strikes Nickless, who’s also a fabric artist, as a vital part of his biography. “Look at the covers — there’s all this patterning at the base of them,” she points out.

Sometime in the 1930s, Petruccelli showed up at the offices of Fortune magazine. “He walked in there off the streets with his portfolio, after taking it all over town,” Mike says. “The art director liked him, and he had three covers in the first year.”

Petruccelli, recalls his son, was known for his sense of humor, which is evident in several of the Helicline works, like Man with Ribbon, published in Collier’s magazine in 1933. In it, a hapless gent attempting to wrap a gift seems utterly consumed by an out-of-control red ribbon.

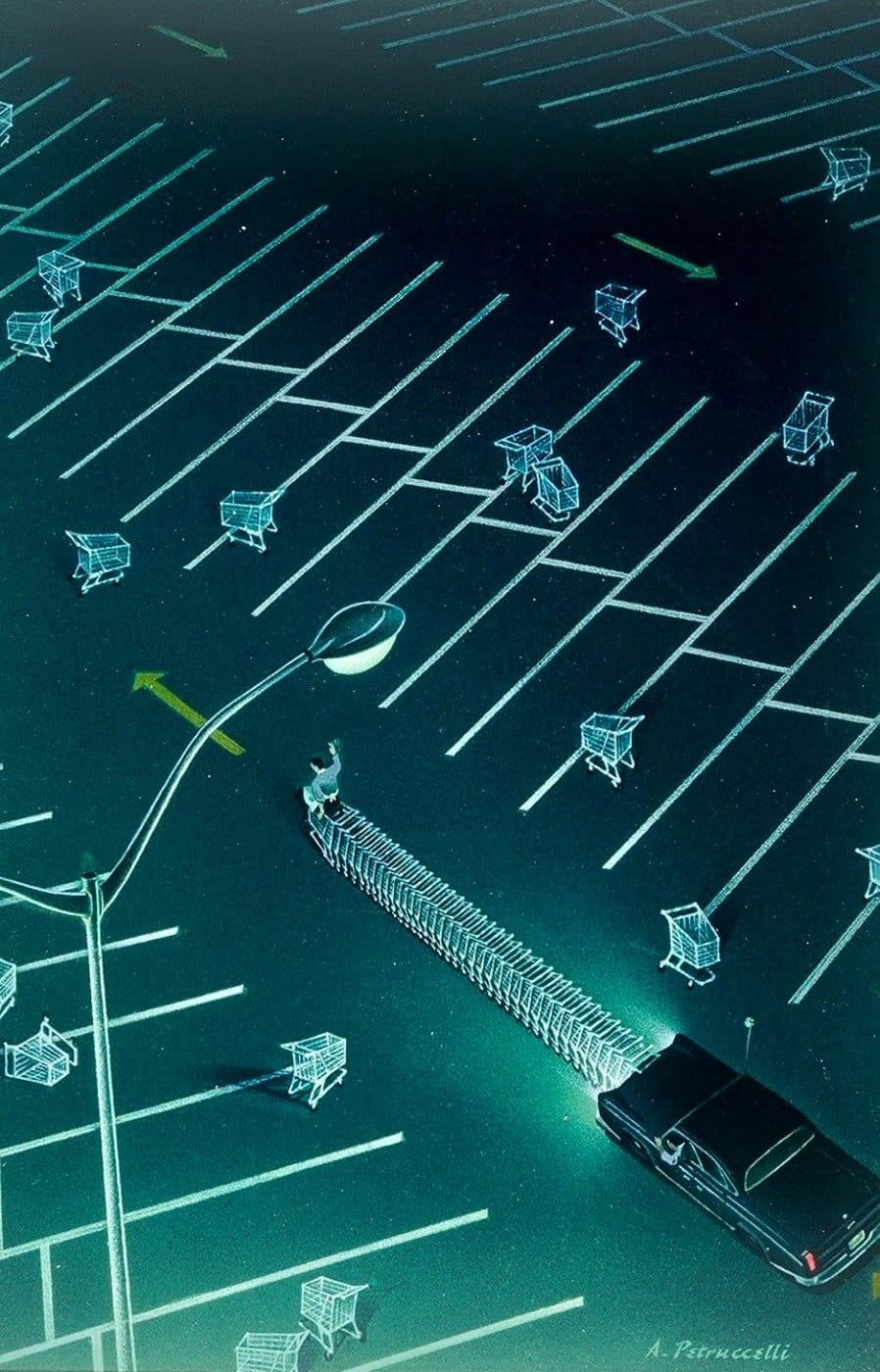

Similar wit imbues Shopping Center, a 1950s cover proposal for the New Yorker depicting a somewhat spooky parking lot at night. Below several empty spaces, a car is pushing a long line of shopping carts at the front end of which is a single joy rider, lit by the car’s headlights and whooping it up as he is propelled forward.

Prolific and skilled, Petruccelli definitely found a market for his kind of art, although it was a grueling grind. “He lived his whole life as a freelance commercial artist,” says Nickless. “It shows how hard you have to work, the connections you have to keep, to do that.”

Once Petruccelli’s works went into print, that was the end of them as far as he was concerned. “To the best of my knowledge, he never sold a painting after it was published,” says Mike. That’s partly because back in those days, “illustrations were not considered art,” says Sherman. “It was what fine artists did to make a living.”

So, when Petruccelli died, his family found all the paintings stacked up. “Basically his entire career was in a closet,” Mike says.

Taken together, the creations in the Helicline show represent a more substantial and consistent oeuvre than that suggested by their original piecemeal appearance in magazines. “I’m biased, but he was so multitalented in both content and in the media he used,” Mike says. “He was always experimenting.”

Mike is pleased with the way Sherman has featured and promoted his father’s work so far. “We’re trying to get him out there and recognized for his legacy. He deserves it.”