The first Art et Industrie gallery, on Thompson Street in Manhattan’s Soho, in 1977 (photo by Rick Kaufmann, courtesy of The Rick Kaufmann Collection). Top: Some of the most influential works from Art et Industrie are now on view at Magen H Gallery. Photo by Deborah Corcos

How many decades must pass before it’s time for a reexamination of a style or movement? About three, thinks Hugues Magen, a longstanding dealer in avant-garde 20th-century decorative arts, both on 1stdibs and at Magen H Gallery, on Manhattan’s East 11th Street.

Magen has organized the first-ever retrospective celebrating the hotbed of creative production that was Art et Industrie, a Soho gallery with three locations over the years, all owned by downtown cultural impresario Rick Kaufmann.

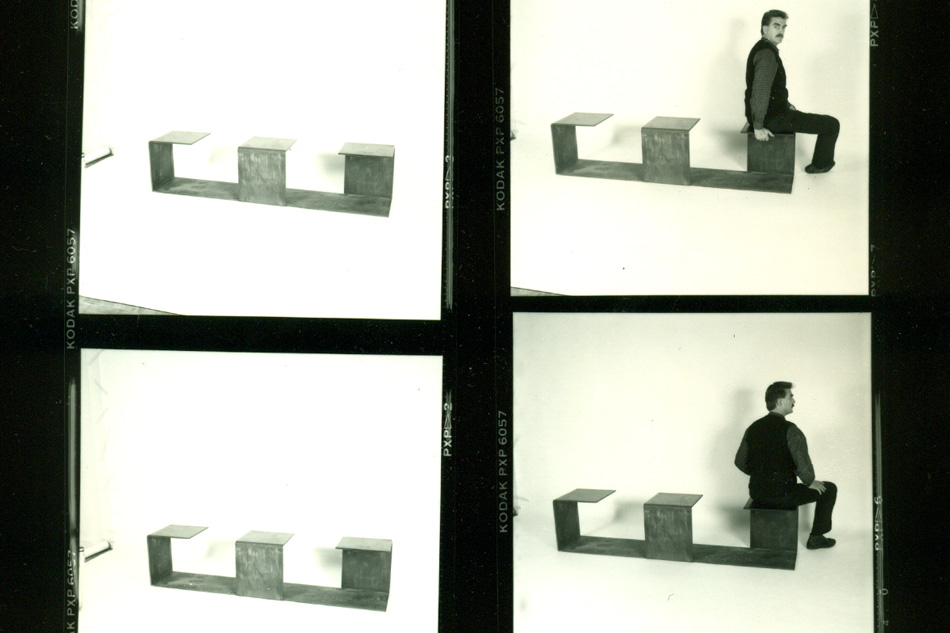

Kaufmann commissioned local artists to take their best shots at designing furniture, which they did with highly inventive results. In consequence, he fostered a revolutionary art-furniture movement that lasted from 1977, when the first Art et Industrie opened, until 1999, when the last one closed.

The Magen H exhibition, “Art et Industrie — A New York Movement,” which runs through December 5, is accompanied by a 236-page, limited-edition catalogue documenting the movement’s entire output. Many of the original players, including Kaufmann, are still around and attended the show’s opening last week.

Introspective caught up with Hugues Magen to find out more.

Art et Industrie was first a publication and then a gallery. How did it become a movement?

It was a French magazine in the 1930s, and Rick Kaufmann chose the name for his Soho gallery, whose intention was to establish a bridge between art and design. Kaufmann looked around for new talent that could create a new kind of furniture. He felt the design of the day was so standardized, and he wanted to give voice to young artists and bring new ideas to market. He would go to them and say, “Would you like to do an exhibition in my gallery? Are you capable of producing twenty chairs?” That’s how the movement started.

Who were these local artists, and what did they bring to the table, so to speak?

Most of these kids had very little background in design, some none at all, and were not trained craftsmen. Terence Main was among the exceptions, having studied at Cranbrook. But they created out of their guts, with new ideas that challenged the standards of the day. Howard Meister came from a family of chair makers. Forrest Myers was a minimalist sculptor. He couldn’t find furniture that was functional but also pleased his eye, so he started making some. Along with James Hong, Jim Cole, Paul Ludick and others, they took a very radical approach to design: bringing in emotions, pushing the envelope to do things that had not been experienced before.

A 1992 group portrait of the Art et Industrie stable of artists. Clockwise from top row, far left: Richard Snyder, Carmen Spera, David Zelman, Rick Kaufmann (gallery director and owner), Jonathan Teasdale, Howard Meister, Mitchell White, Terence Main, Paul Ludick, James Evanson, Forrest Myers, Alex Locadia and James Hong. Photo by George Lange, courtesy of Rick Kaufmann

Was the output of Art et Industrie related to the radical Italian design of that era? The gallery exhibited work by Milan’s Studio Alchimia, and Alessandro Mendini’s Proust chair is on your show invitation.

Postmodernism was in the air, and at that time, Studio Alchimia, definitely the most avant-garde exponent of that movement, was being shown in America. The new thinking was “Less is more is no more — it should be excess.” The Art et Industrie designers were certainly influenced by that.

Forrest Myers stunned the design world in the ’70s with sculptural metal furnishings that resembled tumbleweed, while Richard Snyder’s work, like Cabinet of the Ancient Squid, 1990, was often more sculptural than truly functional. Photo by Deborah Corcos

You’re originally from Paris, and your gallery has been known primarily for postwar French sculpture and decorative arts. How did you become interested in this homegrown, New York City–based movement?

I bought Forrest Myers’s Champagne pink wire chair from Rick Kaufmann’s private collection about 10 years ago. When I first saw it, I was completely disoriented. Here was this object that was obviously a chair in some respect but occupied space in a way that was sculptural. It was more an art object than a functional piece, yet it was comfortable to sit in. I could see that standards were being completely challenged here, and I wanted to further my understanding of the movement and the ingenious ideas of color, shape and message behind it.

Can you expand a bit on what that message is?

What the Art et Industrie pieces have in common is that they pose open-ended questions. They don’t offer solutions for what we perceive as functional or normal uses. Rather, they engage the viewer by seeking possibilities.

Why do you feel that now is the time for a retrospective?

It’s been a couple of generations, and we’ve started to look at the ’80s with more, should I say, compassion. From today’s point of view, the work seems unique and valuable, and it’s starting to influence new design. We’re recognizing the value of what the Art et Industrie designers left us. I want to put the work back on a pedestal and show that there’s a conversation that needs to be renewed.

Visit Magen H Gallery on 1stdibs