January 12, 2025Humans have been attracted to glass objects since ancient times, for their practical uses but also for their magical qualities, the way they catch the sunlight, moonlight and candlelight. Two concurrent museum exhibitions focus on the historical relationship between glass and global culture.

The first is “Sensorium: Stories of Glass and Fragrance,” at the Corning Museum of Glass, in Upstate New York, through February 23. Through 75 perfume bottles and other fragrance vessels, it examines the relationship between glass and scent across centuries and continents.

On display are antique flasks, Chinese snuff bottles, scent burners and contemporary perfume bottles designed by artists like James Turrell and Héctor Esrawe, who creates glass for the Mexican perfume company Xinú.

“The history of perfume is, in some manner, that of civilization,” wrote Eugène Rimmel, a 19th-century London perfumer and cosmetics magnate, the Estée Lauder of his day.

His observation strikes a chord with Julie Bellemare, the museum’s curator of early modern glass (who came to Corning from New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art). “I wanted to explore the millennia-long relationships between glass, perfumery and the storage of scent,” she says, pointing out that the material’s distinctive properties — impermeability, inertness and beauty — make it perfect for encapsulating a substance as fleeting and precious as a scent. The chemical structure of glass ensures that it will not react with the volatile compounds it stores. “I wanted to showcase the evolution of perfume bottles while telling larger stories about science, perfume and luxury.”

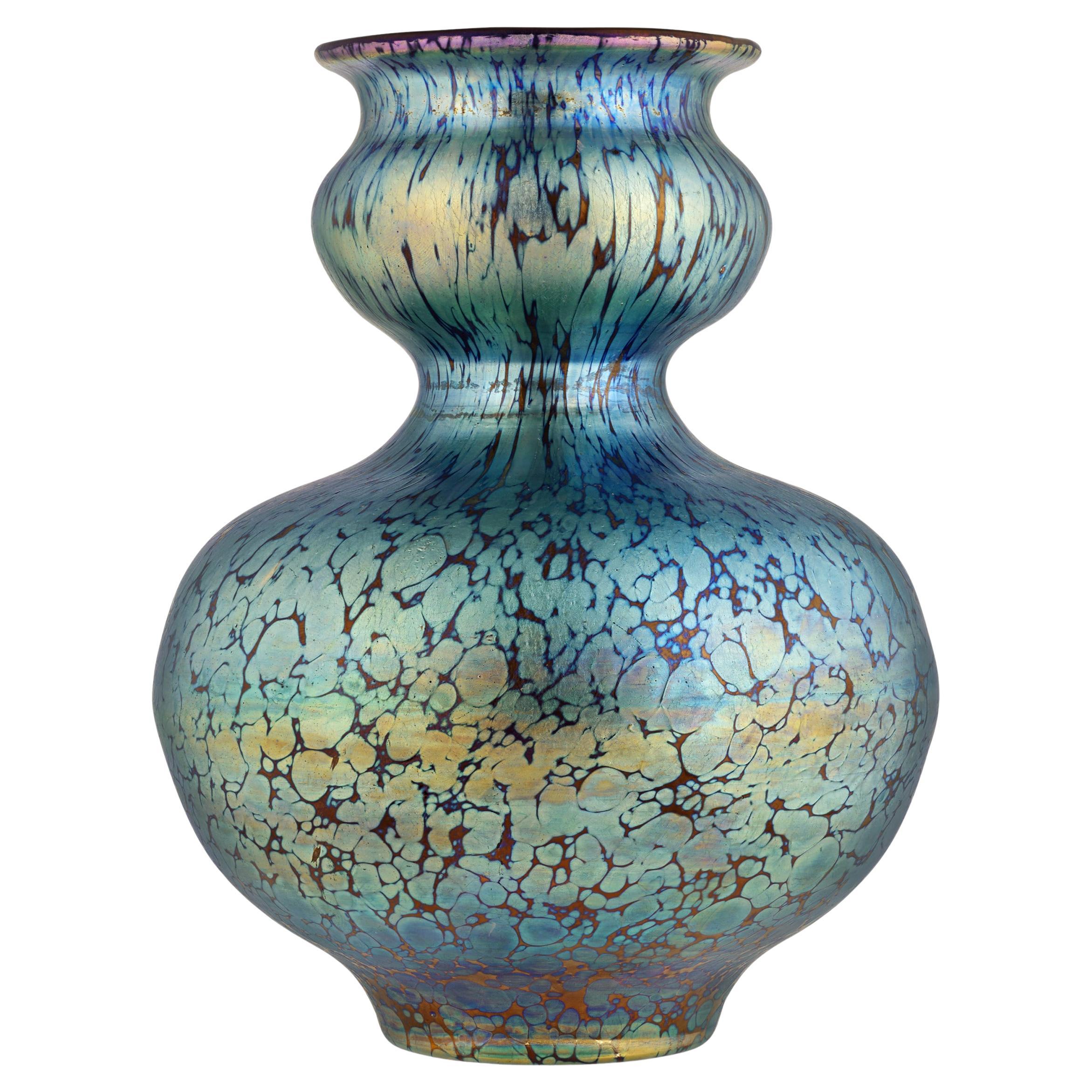

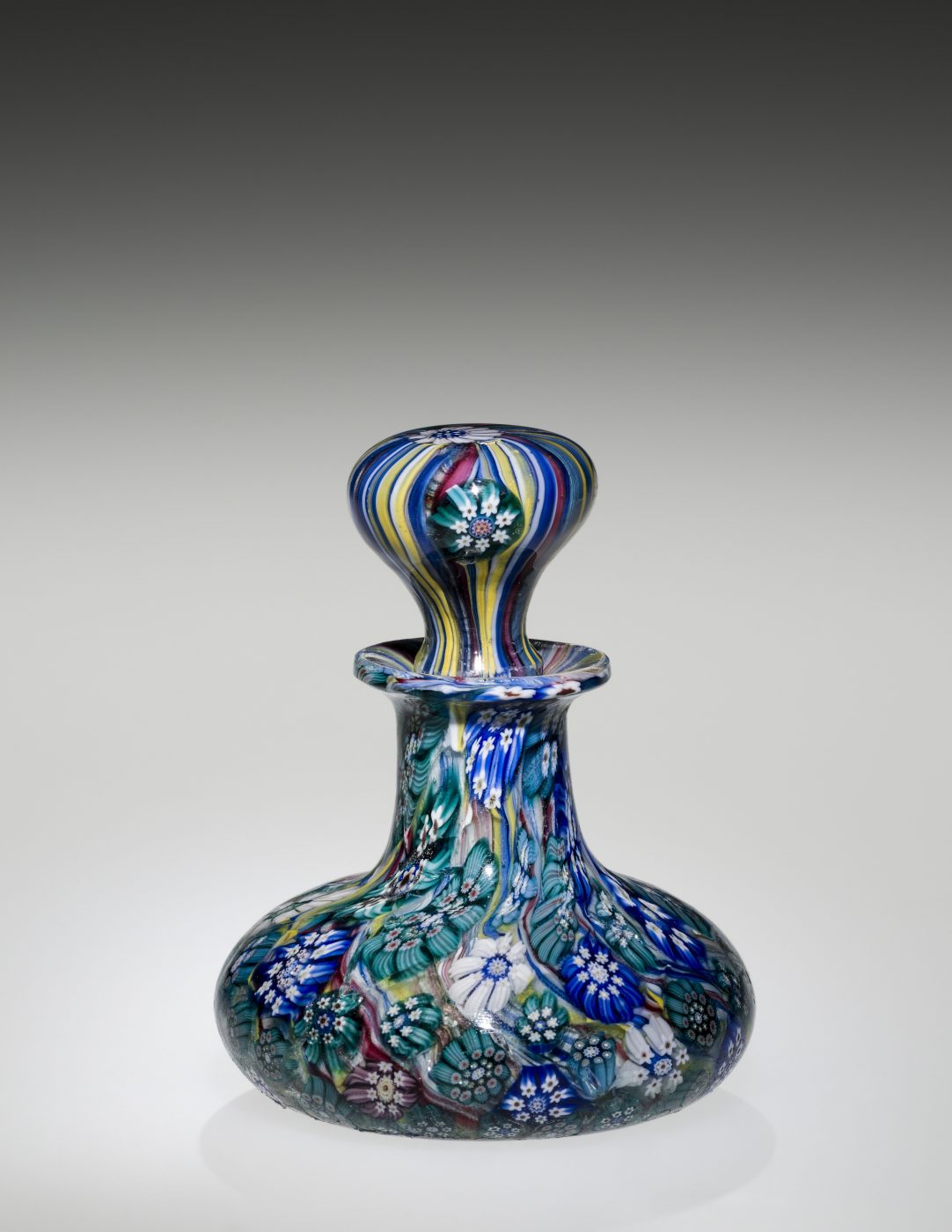

The exhibits are mounted in elegant cases like those in a perfume boutique. One highlights the snuff trade between Europe and China in the 18th century, when Chinese glassmakers developed, carved and decorated tiny glass bottles that could be carried in one’s pocket. Among the items on view is an elegant red glass bottle shaped like a double gourd, with a green stopper attached to a spoon to dispense the snuff (a powdered tobacco mixed with aromatic materials and scented oils).

Elsewhere we discover rosewater sprinklers, popular in the Islamic world after the 11th century, with elegant bulbous bodies and long narrow necks. Rosewater was sprinkled into the air or on visitors’ hands to welcome them into the home. The scent of the famously fragrant Damascus rose was thought to refresh people.

Also from the Islamic world are spectacular examples of the glass produced with gilded and enamel ornamentation beginning in the 12th century.

An 18th-century European wooden casket cradles four glass flasks covered with stylized enamel flowers and elegant ladies. Dutch merchants commissioned clear glass flasks — initially from European makers — and had them elaborately painted in Gujarat, India, with images like those in Indian miniatures. Later the bottles were both made and decorated in India. They were filled with exotic oils and gifted to trading partners and diplomatic allies around the Indian Ocean.

A standout in the show is an early-19th-century perfume container in the shape of a dove from the renowned centuries-old glassmaking center of Beykoz, Turkey, outside Istanbul. Extremely rare today, such bird vessels held scented water or perfume distilled from locally grown roses, tulips and cyclamen. This one is made of opaque white glass with raspberry accents suggesting feathers, wings, eyes and beak. Glass production ceased in Beykoz in the early 20th century because of competition from cheaper European glass, although the city today boasts a fine glass museum.

The show also includes elaborate glass perfume containers from the 1800s, some engraved and with silver mounts, from the historic glassmaking centers in Bohemia and Venice.

In Europe in the early 1900s, fashion designers like Coco Chanel began launching signature fragrances. To create an aura of luxury, they commissioned artists to design the bottles. The innovative French glassmaker René Lalique designed and manufactured perfume bottles for several firms, the products a testimony to his incredible imagination.

Worth, one of the first fashion houses to venture into perfume, hired Lalique in 1924 to create a bottle for a perfume named Dans la Nuit (In the Night). He designed a deep-blue translucent glass globe with raised stars, representing a magical night sky. For a perfume named Les Anémones, from French beauty brand Forvil, Lalique created a stopper adorned with delicate glass anemone petals. He later produced his own bottle with a similar design, called Deux Anémones.

In 1927, he created a perfume burner for Lampe Berger in the form of a green matte-glass artichoke. Such burners were originally used to purify the air in hospitals, with wicks like candles. By the 1930s, they had became home accessories, popular with celebrities like Pablo Picasso and Chanel.

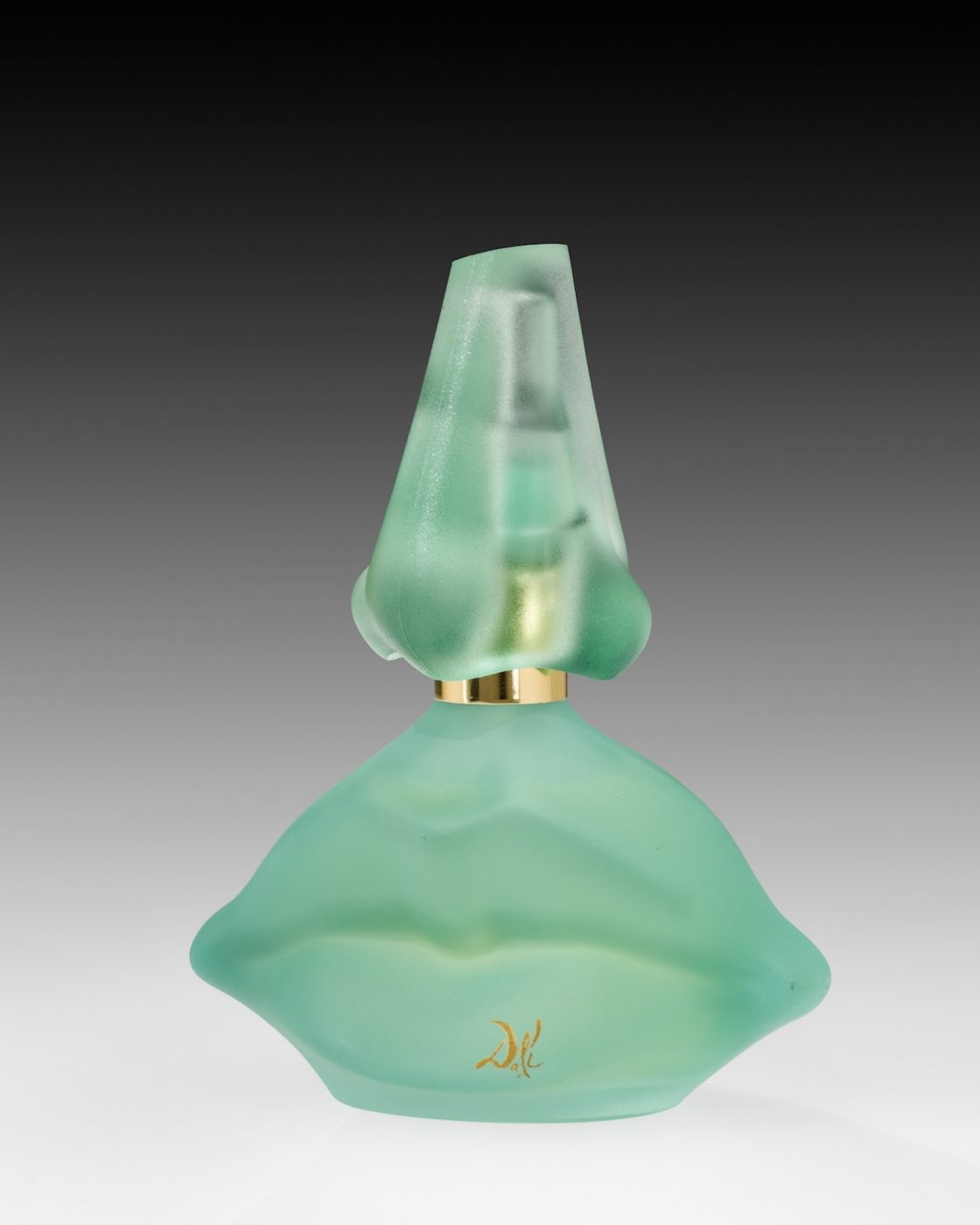

More recently, in 2022, the Lalique factory commissioned contemporary artist Turrell to create both the designs and the scents for a pair of perfume bottles, which are on loan to the show. They mark Turrell’s first foray into art glass, combining his interest in light, space and color with his fondness for the pungent smells of his home state of Arizona. One of his creations, a stunning pale-yellow-and-blue bottle inspired by Egyptian pyramids, is called Range Rider; the other, a smokey-violet form modeled on Buddhist stupas, is called Purple Sage.

Unlike anything in the market, Turrell’s glass bottles are massive, tactile sculptures that embody both monumentality and glowing transparency. “Artists can be drawn to glass for a variety of reasons: to create vessels that combine beauty and function, to work with a substance that captures light or simply to play with fire,” says Bellemare. Many also appreciate the opportunities the medium presents to explore new frontiers through the use of technologies like 3D printing.

Perfume: Joy, Obsession, Scandal, Sin, A Cultural History of Fragrance from 1750 to the Present (Rizzoli), by Richard H. Stamelman, professor emeritus at Williams College, in Massachusetts, contains a quote by Jacques Polge, creator of the Chanel perfumes Egoïste, Allure and Chance: “A perfume is always an expression of its time; it is . . . nothing less than fashion become poetry.” The Corning exhibition proves that the same holds true for the vessels that enshrine the scents.

Equally fascinating is the show “Sand, Ash, Heat: Glass at the New Orleans Museum of Art,” running in the Crescent City through February 10 (purposely coinciding with the Super Bowl).

The institution, called NOMA for short, has a famously extensive collection of glass, including ancient Egyptian amulets; Roman artifacts; Venetian goblets; late-19th- and early-20th-century art glass created by Louis Comfort Tiffany, the Wiener Werkstätte and members of the Art Nouveau and Arts and Crafts movements; American studio glass from the 1960s and 1970s (think Harvey K. Littleton and Dale Chihuly); and contemporary works by such artists as Lynda Benglis and Olafur Eliasson.

With a more ambitious scope than its Corning counterpart, the NOMA exhibition covers 4,000 years of glass production through some 250 of its nearly 5,000 works. Mel Buchanan, the museum’s curator of decorative arts and design, intends to show that glass artworks can be vessels for spreading concepts, designs “and human connection across time.”

The many fine historic pieces in the show — including an extraordinary ancient flask in the shape of a pig, from between AD 100 and 300 — are entrancing, but the contemporary pieces demand a different kind of scrutiny.

The centerpiece of the exhibition is a recently acquired chandelier made by the Black American artist Fred Wilson (a MacArthur “Genius Grant” winner) titled The Way the Moon’s in Love with the Dark.

“It is the conceptual guidepost to the show,” Buchanan says, “its intellectual anchor.”

The work, which was presented at the 2017 Venice Biennale, is composed of a slightly menacing seven-foot-tall black Murano-glass chandelier dripping with black crosses. This is enveloped by cylindrical clear-glass-and-metal Turkish lamps that hang from chains attached to a fixture on the ceiling.

Its title comes from an unpublished novel by Alexander Pushkin that was inspired by Shakespeare’s tragedy Othello, which centers on a Moor and his fair-skinned wife. Pushkin’s great-grandfather was an African enslaved by the Ottomans and later and brought to the court of Peter the Great, where he was raised as Peter’s godson and became a noble. As Buchanan explains in the catalogue, for Wilson, the chandelier represents the Pushkin ancestor’s “transcultural experience by overlaying Ottoman-design lamps over the Black European glass core.

“The piece is about Blackness and its connection to glass,” she continues, “as well as how opposing traditions are contained within single objects.”

She also calls out a 19th-century New Orleans souvenir goblet. Its ruby-hued glass is engraved with famous local sites, including ships on the Mississippi River, the St. Louis Cathedral and the cupola of the St. Charles Hotel.

“The hotel was a site for auctioning enslaved people,” Buchanan writes in the catalogue, noting that such historical objects “are multi-faceted, containing stories of both grandeur and oppression.”

When the staff was organizing the show, “we were asking ourselves new questions,” she says. “We are studying objects of the past as a way to study history, getting into the past through a different highway.”

Such works are, she says, “ideas in glass.”