April 3, 2022Eccentric, idiosyncratic, original. None of these adjectives does an adequate job of describing the Cosmic House — the London home of American-born architect, theorist and landscape artist Charles Jencks, who was a tireless vocal champion of postmodernism.

Jencks died in 2019, and last fall, with little fanfare, his house opened to the public with limited admission and hours. Almost immediately, it became the ticket for architecture and design lovers — an eclectic 20th-century foil to Sir John Soane’s house, created more than 150 years earlier in another borough of London — and a hard-to-get one at that. Currently closed for the winter, it reopens on April 6.

Born in Baltimore in 1939, Jencks moved to England in the 1970s, after completing a master’s degree in architecture at Harvard. In 1978, he and his English wife, Maggie Keswick, bought a four-story Victorian villa in London’s Holland Park.

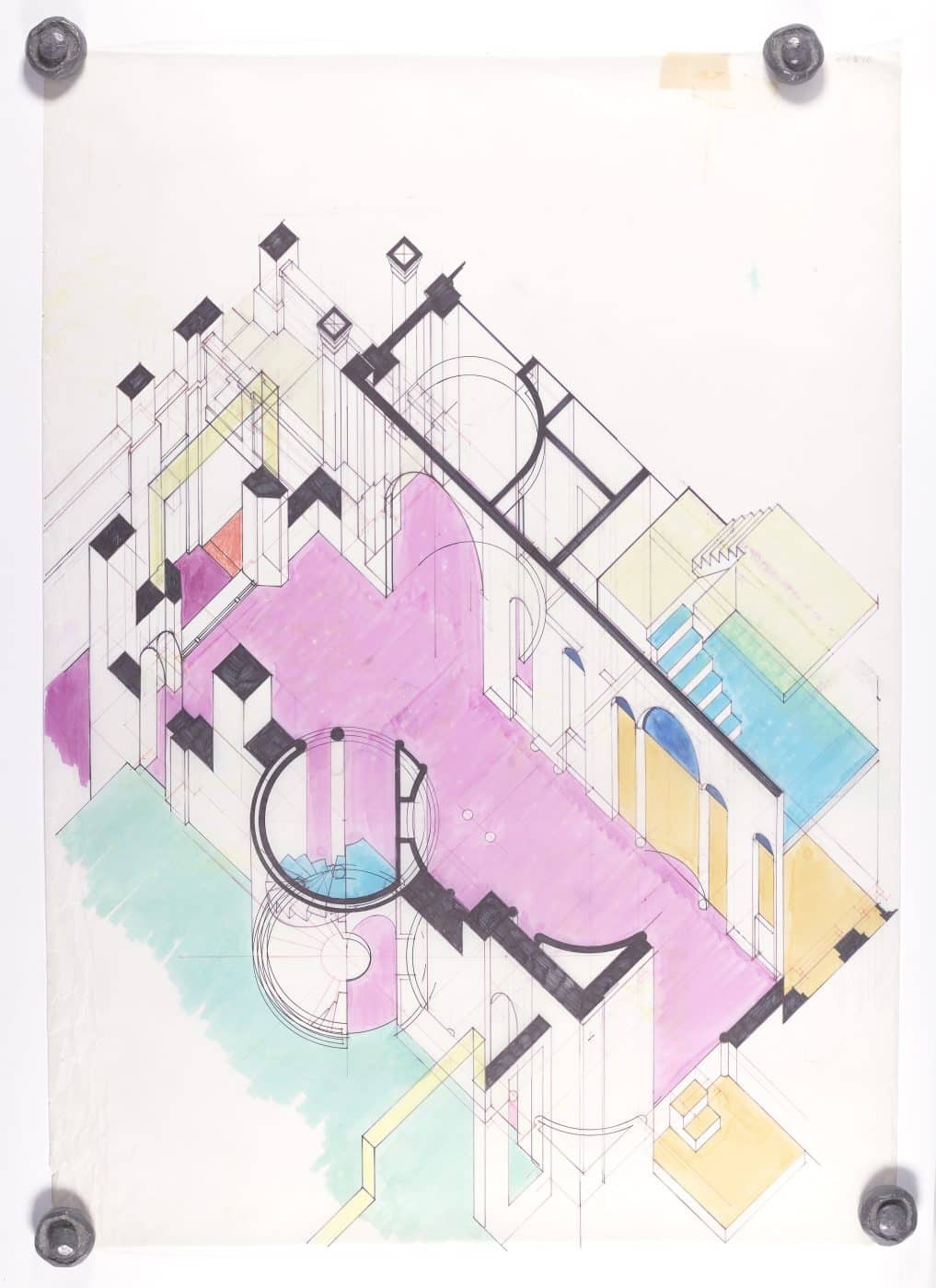

With the help of architect Terry Farrell, Jencks transformed the house into an exemplar of his theories on postmodernism, the movement that rejected the austerity of modernism and found formal and ornamental inspiration in historical design, sometimes tweaking those motifs to irreverent effect.

Jencks was interested in architecture filled with allusions and cultural references. He was also fascinated by cosmology — the study of the nature of the universe — and his Cosmic House is both a passionate and provocative manifesto of these interests.

The elegant facade of Jencks’s stucco-fronted house on Landsdowne Walk gives little hint of what lies within, although an observant visitor is thrown a few clues: a stylized fanlight, a vertical mail slot in the front door and not one but two large doorknobs. (Which one opens the door?) Once inside, one’s sense of depth perception is immediately jolted by the presence of no fewer than 13 mirrored doors in the entrance hall, one of them (but which is it?) leading to the so-called Cosmic Loo.

Today, the public entrance is through a newly designed gallery at the basement level. Here are displayed materials from the Jencks archive outlining the history of the building and some of the key influences behind its design.

Visitors are also encouraged to watch a brief film about the making of the house before continuing up to the ground floor. They ascend by way of a cylindrical staircase that is meant to symbolize the sun and is structured to suggest the double helix of a strand of DNA.

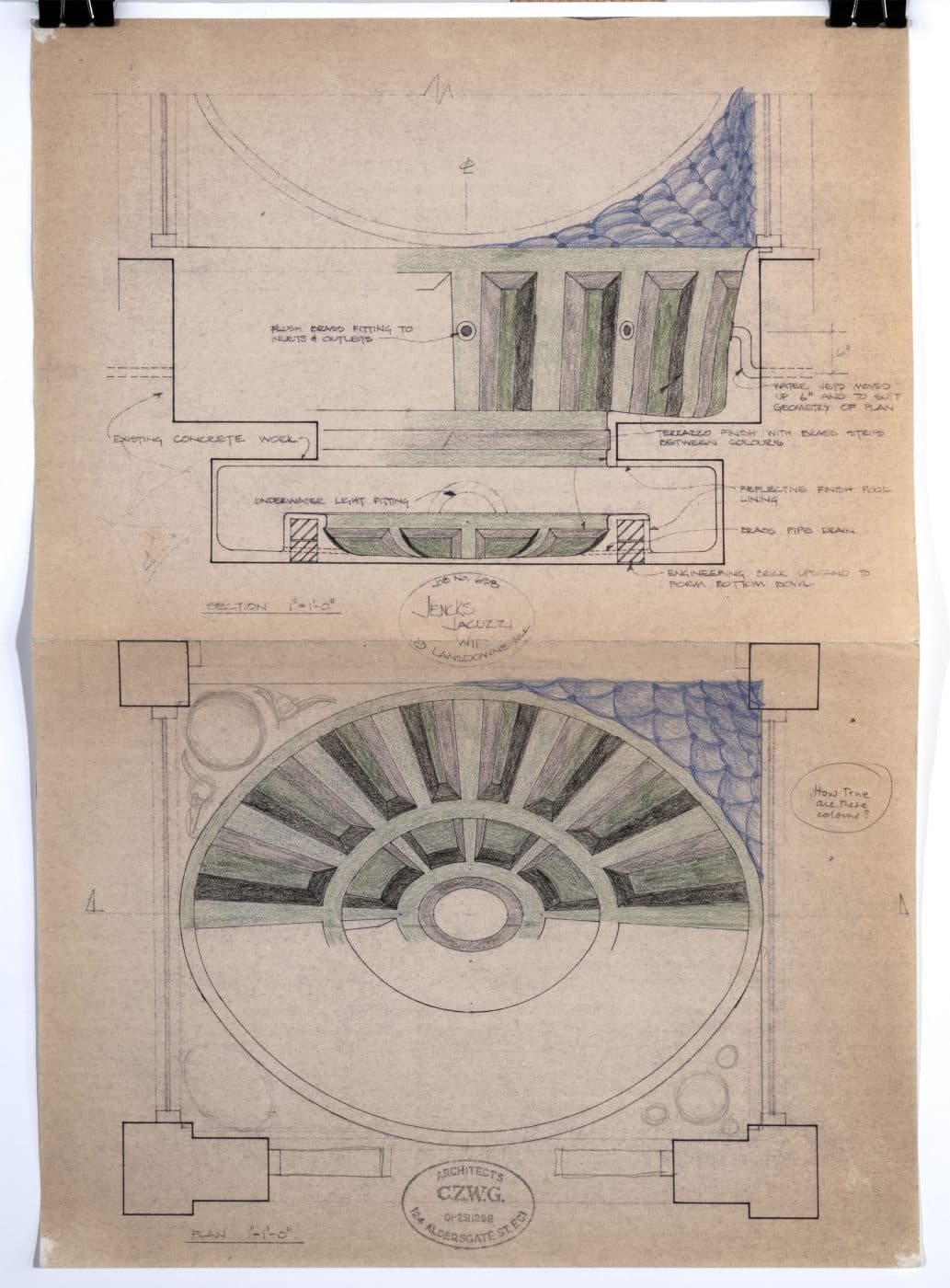

En route, one passes an alcove containing an upside-down marble dome that serves as a spectacular Jacuzzi, its form loosely inspired by Francesco Borromini’s dome for the church of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane in Rome. (Elegant though it may be, according to Jencks’s daughter, Lily, the plumbing was faulty and the tub/pool was difficult to get in and out of.)

Throughout the house, ceilings morph into sails or tents, elliptical domes are mirrored or painted, floors have messages stenciled on them and busts of philosophers, poets, mythological figures and astronomers admired by Jencks greet you at every turn.

Jencks named the main rooms on the ground floor for the seasons. The Winter room faces north and represents the beginning of the year. Painted in dark colors, it is dominated by an oversize fireplace designed for Jencks by prominent American architect Michael Graves. An adjoining sitting room, Spring, also features an oversize Graves-designed fireplace. (Jencks apparently rejected the design proposed by Rem Koolhaas, another good friend.)

Perhaps the most charming space on this floor is the kitchen and pantry, dubbed Indian Summer and chockablock with references to Indian architecture. Here, a frieze decorated with wooden serving spoons frames statuettes of Indian gods mixed in with teapots and crockery.

The cabinet above the oven bears the inscription “The Temple of Heat,” and the one above the sink “The Temple of Water.” Three freestanding closets with decorated doors conceal kitchen tools and a refrigerator. This could be the Mad Hatter’s kitchen in Alice in Wonderland — Jencks is said to have remarked to guests, “If you can’t stand the kitsch, get out of the kitchen.”

Another flight of stairs brings visitors to Jencks’s extensive architectural library. Since he believed bookcases to be visually boring, he designed these to complement the books they hold: A domed form, for instance, contains books on ancient Roman design while a pyramidal shape holds volumes on ancient Egypt. There is nothing dull about this library, and to house his large collection of slides, Jencks created a tall, gabled, freestanding tower, which he named his “Slide-Scraper.”

The garden-facing main bedroom — the calmest and most beautiful room in the house — is also on this floor. Painted in three shades of white with a gently subdued decorative scheme and fitted with built-in wooden furniture, it feels like it could be the work of Charles Rennie Mackintosh.

Jencks designed bedrooms for his two children, John and Lily, on the house’s topmost floor, and his playfulness is more evident here than anywhere else in the house. Carved-out dormer windows sit under the eaves of the roof and steep steps lead to interconnected sleeping lofts. The rooms would delight any child.

The garden adjoining the house consists mainly of a topiary-bordered lawn that leads to mirrored windows set in an archway. This gives the illusion of more lawn but is surprisingly restrained for Jencks whose later creation, the Garden of Cosmic Speculation, at his home in Scotland, is unquestionably one of the most original and seminal gardens in the British Isles.

Although many visitors may be overwhelmed by the relentless layers of symbolism and arcane references throughout the house, in the end, Jencks the designer triumphs over Jencks the polemicist. It is the wit, erudition and irresistible charm of this family home that will stick with you long after your visit concludes.