Costume jeweler Ciner makes every piece to order — and by hand — in its New York workshop, enabling them to experiment with color, like these blooming orchid brooches, available in shades of green, and pink, and in silver, gold and black. Top: Carolyne Roehm collaborated with the firm to create a nature-inspired collection that includes this bee chain belt, textured dragon chain belt, organic gold cuff, black dragon cuff, dove ring and bee button earrings. Story styled by Lisa Lee at Sarah Laird

January 26, 2020What defines “fine” jewelry? For many aficionados, there’s a clear line separating the golden wheat from the gilded chaff. But the pieces made by Ciner, a 128-year-old costume jewelry house with a glittering past to rival some of the hautest high jewelers, call into question our notions of what constitutes preciousness. Quality? Craftsmanship? Painstaking detail? Ciner’s jewels have them all in spades. Sure, they may sport crystals where others boast diamonds, but does one judge a painting on the type of pigments used? It’s Ciner’s commitment to hand-crafting pieces the traditional way — no matter the material — that has made the firm a collector’s secret for more than a century. And it’s what led Carolyne Roehm, the lifestyle guru and doyenne of Nouvelle Society, to collaborate with it on a new collection that may be short on carats but is long on style.

Much of the brand’s allure can be traced to its origins in fine jewelry. Emanuel Ciner, an Austrian immigrant, founded the firm in Manhattan in 1892, crafting pieces from the traditional precious gems, gold and platinum. But World War I and the Great Depression caused purse strings to tighten and materials to become scarce. Rather than try to weather the economic downturn, which shuttered many other American jewelers, Ciner made the risky transition from fine to costume — virtually uncharted territory.

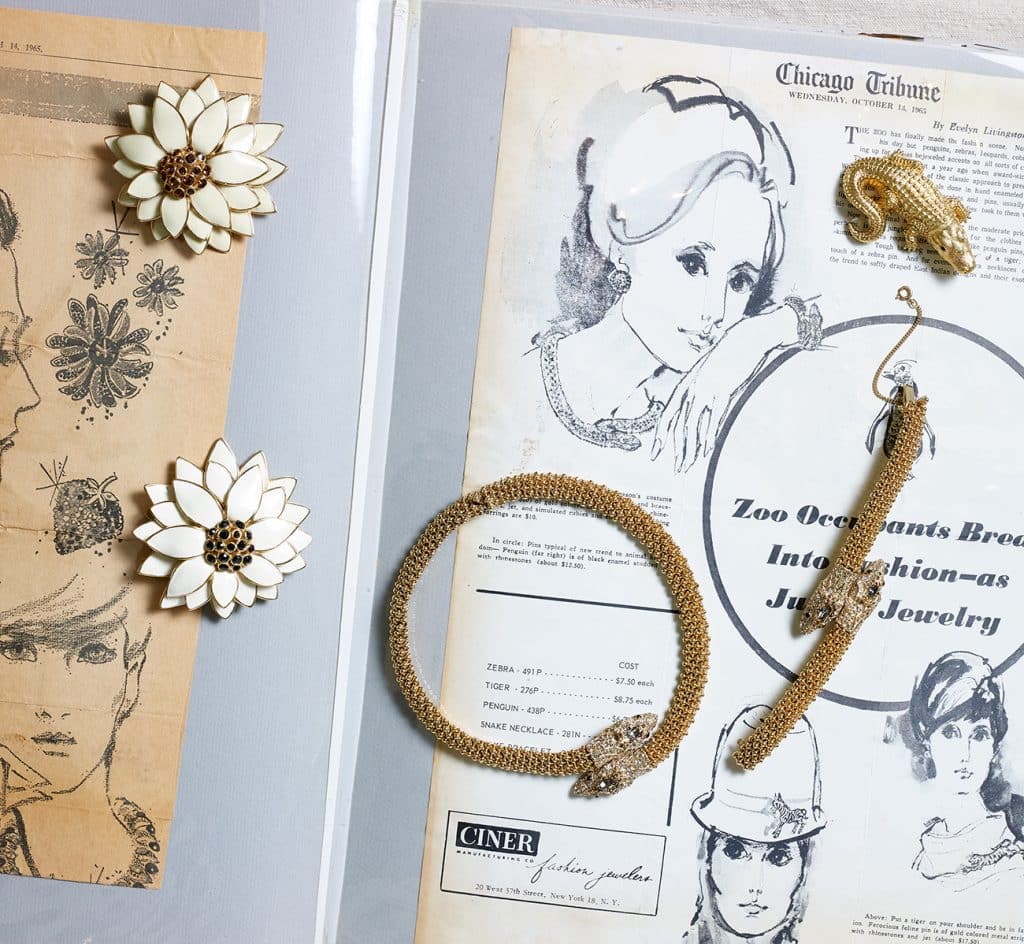

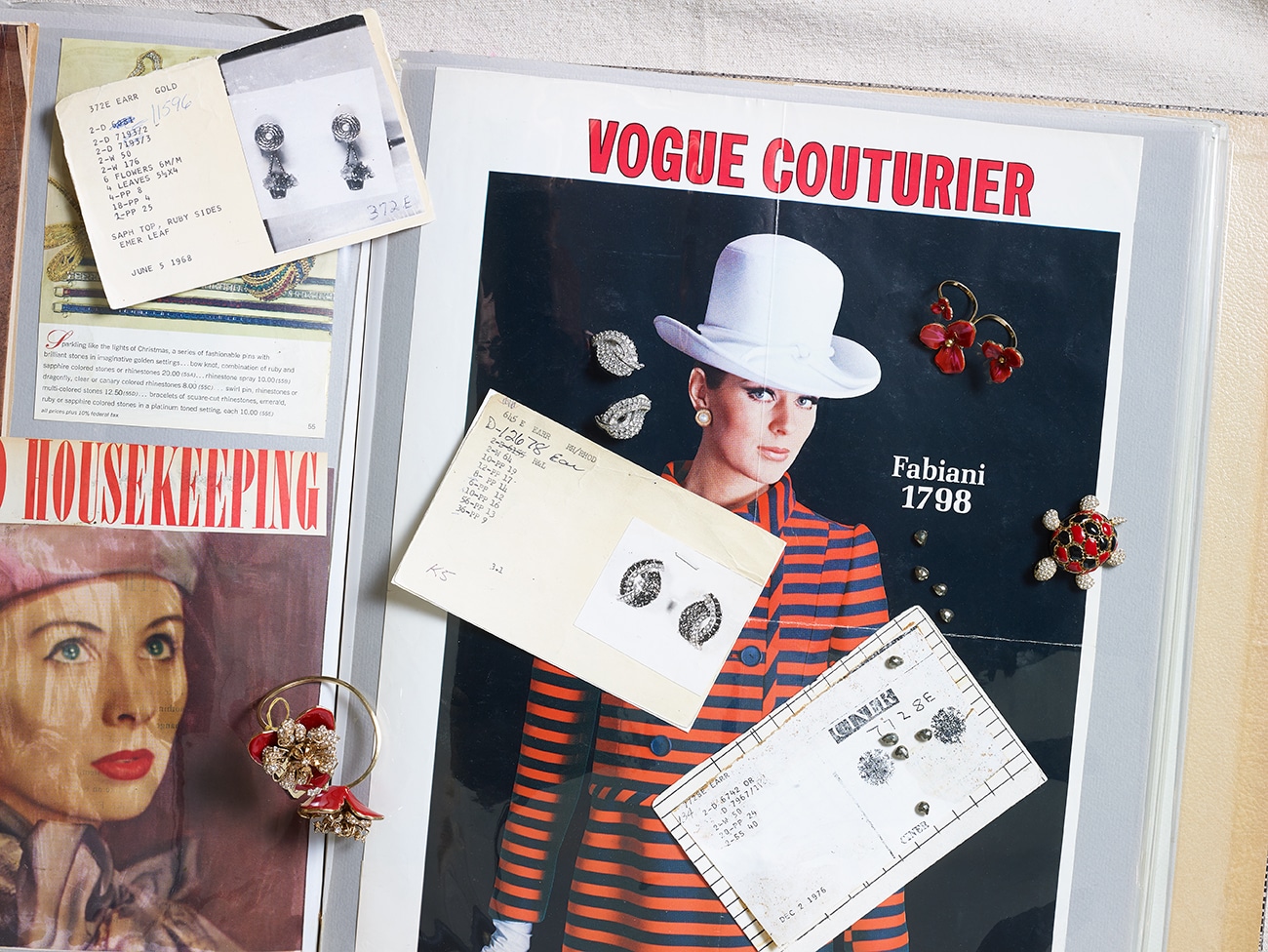

Ciner has archived decades of company history in massive scrapbooks that contain newspaper ads, magazine spreads and photos signed by the celebrities who have worn its pieces, such as Jayne Mansfield (top) and the Gabor sisters, Zsa Zsa, Eva and Magda (below). The pieces shown here include the crystal-encrusted chandelier necklace, Nerissa necklace, cicada necklace and Signature flower necklace.

Emanuel Ciner’s sons, Irwin and Charles, introduced an array of innovations — rubber casting molds, which are especially durable and produce higher quality results, and white metal alloys, which affordably mimic the look of more precious materials — that would become the standard for costume jewelry. During World War II, Ciner’s advanced molding technology was utilized by the U.S. military to produce munitions and tools. This arrangement gave the firm access to the heavily rationed metals it needed for its jewels, enabling it again to endure conditions that drove others into bankruptcy.

Many of Ciner’s whimsical minaudières, some of which date back to the 1930s, include rings that allow them to be dangled from their wearer’s hand. The minaudières seen here include the Bethesda, Scattered Flower, Signature, and Ines x Ciner Closed Signature.

The company hit its stride in the 1960s, when its jewelry was sold at some of the country’s toniest stores, even garnering an Andy Warhol–illustrated ad for Bonwit Teller. Its pieces were worn by the era’s brightest stars. In the famous 1957 Joe Shere photo of Sophia Loren sneering at Jayne Mansfield’s décolletage, Mansfield is resplendent in shoulder-grazing Ciner earrings.

Ciner is unique among costume jewelers in that its pieces aren’t imitations — they are coveted in their own right. Elizabeth Taylor, a voracious jewelry collector with a taste for the very finest, was a longtime client. Several suites of Ciner jewels were included in the 2011 Christie’s sale of Taylor’s collection, with one group of rhinestone-studded ear clips and a bracelet fetching $15,600 — more than 100 times the auction estimate. It’s a reminder of a time, not so long ago, when women of great style wore fine and costume jewelry with equal aplomb, often at the same time.

Ciner records the components for each piece, a recipe of sorts, on index cards that are filed in library card cabinets. Here, rhinestone earrings, a floating flower ring and turtle ring.

In fact, a 1966 New York Post article heralded the vogue for mixing high and low, citing among its followers fashion luminaries like Diana Vreeland, the Duchess of Windsor and Jacqueline Kennedy, who, it noted, “often wears Ciner’s simulated pearls with her real jewels.”

Carolyne Roehm drew inspiration from Ciner’s archives and her own jewelry when designing the Birds & the Bees collection for the brand, whose proceeds will be donated to shelters for homeless animals. Here, she wears pieces from the Carolyne Roehm x Ciner collection: three-drop crystal bee earrings, bee chain belt and dove cuff.

The brand continues to be worn by discerning women who take style seriously, like Roehm. In the 1980s, as a fixture of the uptown circuit and successful fashion designer, Roehm was a lifestyle influencer before the term existed. What drew a woman with unfettered access to luxury’s highest strata to collaborate with a costume jeweler? “The make, the quality,” says Roehm, who learned about Ciner from her friend Lisa Kopecky after admiring the bejeweled clasps on handbags Kopecky had designed. “These are people making an artisanal product. Even rarer, it’s made in New York.”

Today, the company — now run by Emanuel Ciner’s granddaughter Pat Ciner Hill and great-granddaughter Jean Hill — continues to adhere to the same exacting production specifications. Ciner is the only jewelry house in New York, and likely the United States, that manufactures all its pieces entirely in-house. Each begins with dozens of elements that are cast in rubber molds and then individually filed and polished, plated in a particularly thick layer of 18-karat gold or rhodium, assembled on the bench and painted with enamel or set with stones.

Every step is performed by hand by craftsmen, many of whom have been with the company for more than 30 years. The process is nearly identical to the one used by the most esteemed maisons on the Place Vendôme — a process that most costume jewelers have deemed too time-consuming or costly. But it’s something on which Ciner isn’t willing to compromise. As Ciner Hill puts it: “We’re stubborn enough to keep it going.” As for the materials they use, she says, “What the stones are shouldn’t matter. It’s about how it looks and how you feel when you put it on.”

Roehm conceived the idea for a line of nature-themed jewelry while recovering from a serious illness. It represented a return to her earliest passion: jewelry. Her first major purchase as a little girl was a tiara from a Sears-Roebuck catalogue. Later, as an assistant to Oscar de la Renta, she often worked with Kenneth Jay Lane — another pioneer in making faux fabulous — on conceiving jewels, buttons, and bibelots to accessorize de la Renta’s collections.

Clockwise from left, a golden sputnik cuff, pin and cocktail ring

“With everything I do, whether it’s interiors or gardens or jewelry, they all have certain elements that are specific to that craft,” Roehm reflects. “After that, the elements are all the same: It’s still line, color, texture, proportion. But I love designing jewelry because I get to wear it!”

Because Ciner makes every element of every piece to order and under one roof, it has a unique ability to customize designs, or even create entirely bespoke ones. The company’s extensive library of models provides a wealth of inspiration. “Our body of work is humongous, and it spans every trend throughout every era we’ve been in business,” says Kris Ciulla, Ciner’s vice president of design and sales. “We still make a lot of those old pieces, but to refresh and create newness, we work from our archival models to craft new pieces.”

Roehm’s design process began with sifting through Ciner’s archives and bringing in examples from her personal collection. Her aim was to combine elements from both with a modern eye and irreverent spirit. One of Roehm’s metal belts, a replica of the funky Cartier gold vermeil one Jackie O made famous in the 1970s, inspired a chain link adorned with bejeweled bees that can be worn as a belt or necklace. She borrowed the bee motif from Ciner pieces like au courant hoop earrings and an Art Deco–era diamanté bracelet.

Ciner’s eclectic collection of rings ranges from massive bejeweled insects to bands set with sleek cabochon stones.

More than just a pretty ornament, the bee, for Roehm, is a powerful symbol. “Their body is too heavy for their wings so, aerodynamically, a bee shouldn’t be able to fly, and yet it does. Joan Rivers was a big collector of bee jewelry. She said, ‘I’m like a bee: I’m not supposed to do these things, but look what I can do.’ ”

Other motifs drawn from past Ciner designs, including a chinoiserie dragon and a graceful dove, are rendered as sculptural pendants and cuffs. These elaborate designs are balanced by an array of more basic ones in Ciner’s signature 18-karat gold plate: hefty chains, sleek cuffs, crystal-studded drop earrings.

Many members of the Ciner team, seen here with founder Emanuel Ciner’s granddaughter and current leader, Pat Ciner, and her daughter, Jean Hill (front row right and left respectively), have been with the company for decades.

All the proceeds from the collection, aptly named “the Birds & the Bees,” will be donated to shelters for homeless animals. Roehm, who lives with seven dogs at her estate in Connecticut, was adamant that this project, conceived after narrowly surviving her illness, be an opportunity to give back. “I did a personal analysis of the things I love and enjoy the most,” she recalls of her days of recuperation. “One of the things I enjoy the most is designing, period. And one of the things I love the most is animals, especially my baby dogs.” Roehm is already plotting the next iteration of her Ciner collection. “I’ve got to make some dog jewels too — we’re working on it.”