December 2, 2018“Collections sometimes evolve,” writes French creative director and stylist Daniel Rozensztroch in his new book, which takes us inside his residences. Above: The furniture in his Paris loft, he tells readers, “is mainly vintage industrial…an essential vehicle for showcasing all my collections.” Top: He has long gathered assorted iterations of the letter R, “from all sorts of signs, from various time periods, and in many sizes.” All photos by Francis Amiand

For collector Daniel Rozensztroch, it all started when he was a teenager, with a simple round dish: a 19th-century bowl for eggs made of thick brown glass that reminded him, he says, of “a gigantic version of a wine glass.” He bought the piece from an old-fashioned dairy store just after it closed and has never looked back.

Today, Rozensztroch’s Paris loft overflows with thousands of artworks, antiques and flea-market finds from around the world. But most of these “treasures” are utilitarian objects, humble everyday things like spoons, metal strainers and wire hangers that chez lui are given a second life.

“I’m obsessed with objects, fascinated by their functions, their history, their origins, their symbolic meaning, their very banality,” he says. “Claude Lévi-Strauss expressed it well: ‘Objects are what matter. Only they carry the evidence that throughout the centuries something really happened among human beings.’ ”

Rozensztroch is a much-lauded stylist and designer. He’s the creative director for the design magazine Marie Claire Maison and the artistic director of the trendy Parisian concept store Merci. He also writes and designs books on the art of living — more specifically, his passion for ordinary domestic objects — including Hangers (2002), Spoon (2017) and Herring: A Love Story (2014).

Chestnut wood pitchers formed by 19th-century French shepherds sit on an 18th-century Italian sculptor’s table from the Academy of Fine Arts of Carrara in Italy.

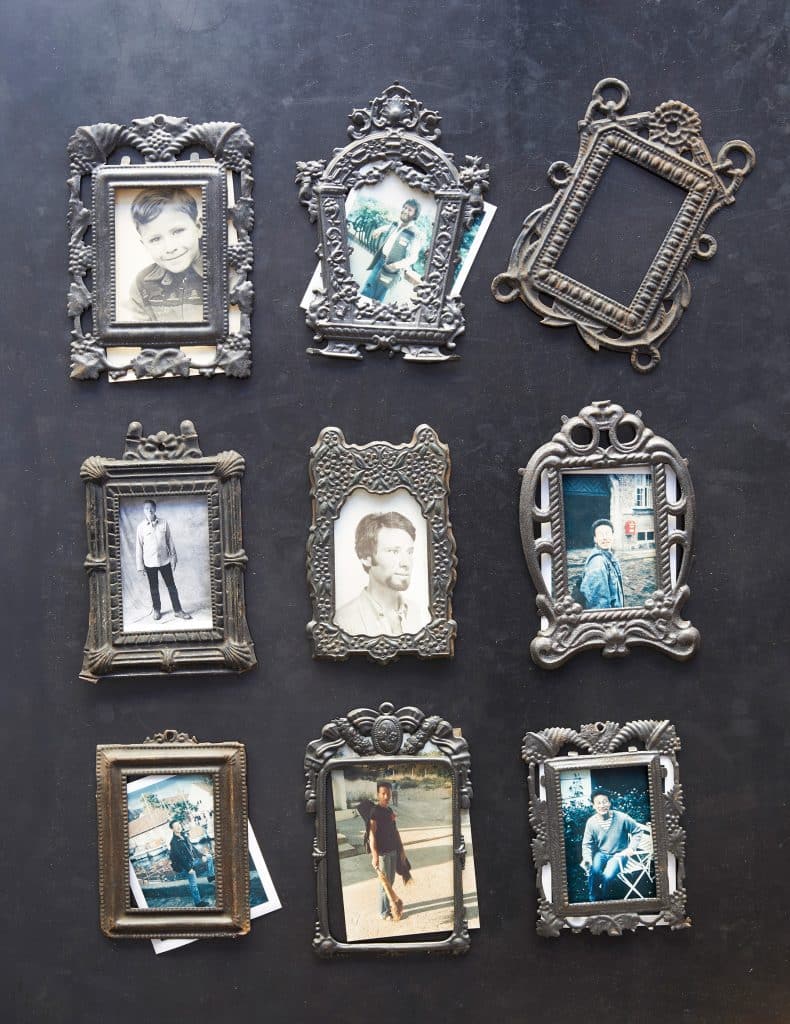

A Life of Things (Pointed Leaf Press), Rozensztroch’s most recent book, offers readers a glimpse of the thousands of compulsively collected artifacts that fill his cabinet-of-curiosities apartments in Paris and Nice. The items include both the rustic and the exquisitely crafted: Provençal oil lamps, tin frames, sailor-themed erotic objects, Jin dynasty vases, terracotta bee smokers, Czechoslovakian glass-bead Christmas ornaments, Japanese snack plates from the 1930s, American tinplate milk skimmers.

“I am constantly traveling to scout out things for my work, and wherever I end up, the very first thing I do is go to the flea market or the souk,” Rozensztroch says. “It’s like an addiction — I get feverishly excited. Surrounding myself with objects feels like a primitive need, as the sense of abundance reassures me. It lessens my anxiety about being deprived.”

Rozensztroch was born on France’s Côte d’Azur in 1944, during World War II, to Jewish parents. His mother and father (of Polish and German ancestry, respectively) had left Paris to seek refuge in Cannes, where they were taken in by a family. They stayed there, in hiding, until the end of the war, when they moved back to Paris.

Rozensztroch’s friend and occasional collaborator Paola Navone designed the table in the Paris loft, where, he writes, “a collection of vintage industrial metal cabinets creates a separation between the kitchen and the dining area.”

Rozensztroch studied at the École nationale supérieure des Arts Décoratifs and, after graduating, found employment in an interior architecture firm. The job, however, left him feeling creatively starved. “I couldn’t bear the idea of ‘good taste,’ of designing everything in a manner that’s standardized, homogeneous, as if everything were coming from a kit. After a few years, I almost had a nervous breakdown,” he says, laughing.

In the early 1970s, he opened a small boutique, Oggetto, on Paris’s Left Bank and started collaborating on books as a stylist. In particular, he contributed to “Everyday Things,” a series published by Abbeville Press whose subjects include garden tools, kitchen ceramics, glassware and wire — “books that both teach about things and change the way we perceive humble objects, helping us see that they can be little masterpieces,” he says. Other volumes explore interiors, from lofts around the world to houses in Greece. In 1980, he began working with Marie Claire Maison. He has since designed wallpapers and organized exhibitions devoted to his beloved collections.

“A collection can be three or three hundred objects,” Rozensztroch says. “My collections always start with one piece. It’s not superfluous or decorative, it’s something essential, necessary, something that keeps me company. I use it, I eat or drink or cook with it. It’s like a love story, like a companion, and the search for these objects is obsessive and ongoing.”

For example, he continues, “I have a cabinet full of eighteenth-century French glassware that I have been buying up for years. I’m not going to confine it or store it away. I love my glasses, I drink out of them every single day. And if one breaks, well, it’s not the end of the world — I have so many others.”

In his Nice apartment, which faces the sea, Rozensztroch writes that he “wanted to recreate a vacation atmosphere to remind me of my childhood on the Côte d’Azur.” A contrast to the Paris home, this was meant to “house another kind of collection, lighter and more fun.” Rattan mirrors from the 1950s, interspersed with three contemporary ones by Navone, hang over the couch, and a vintage railway cart serves as a coffee table.

Tucked away in the trendy Haut Marais neighborhood, Rozensztroch’s 1,000-square-foot Paris apartment occupies a 17th-century manufacturing plant that once housed a toy factory owned by Gustave Eiffel. He renovated it in collaboration with architect Valérie Mazerat, a close friend, creating an open loft whose floor plan allows him to move easily from one area to another.

“I’m obsessed with objects, fascinated by their functions, their history, their origins, their symbolic meaning, their very banality,” says Rozensztroch, seen in the reflection of one of his rattan mirrors.

In the space, Rozensztroch mixes old and new, high and low, all arranged in a kind of orderly disorder. The parquet floors were made from wood reclaimed from old wagon trains by Atmosphère & Bois, in Belgium. A Napoléon III metal case piece is paired with items salvaged from an old garage; classic industrial furniture with a cabinet from a dental office. There are stainless-steel bookcases from Metalsistem, an Eames rocking chair, vintage 1950s perforated-metal shelving by Mathieu Matégot, industrial Tolix tables and chairs, hammered-copper stools from Lebanon and a Chinese country stool. A Noguchi lamp is juxtaposed with a French Art Deco Marius-Ernest Sabino light, one of the rare pieces he inherited from his parents. A tabletop might hold a quirky combination of vintage French glasses, earthenware by the famous 18th-century French pottery manufacturer Niderviller and flatware from Ikea.

In addition to the Paris loft, Rozensztroch has a vacation house in Greece and a residence on Nice’s main oceanfront avenue, the Promenade des Anglais, in a former army barracks built around 1830. Working with his designer friend Paula Navone, he refurbished and reorganized the space — which features three balconies overlooking the sea — to create an open floor plan that serves as something of a showroom for his collections.

Designed to look like dishes piled with seafood, the French Majolica plates hanging on a wall in the Nice home represent what Rozensztroch refers to as the sort of “bad taste” his mother would have reviled.

Most of the furniture is vintage and was discovered in flea markets or local boutiques. Rozensztroch covered one wall with vibrant, kitschy French Majolica plates that look like dishes of seafood. They were made in Vallauris in the 1950s and evidence what he calls the kind of “bad taste” his mother would have hated. On another wall, over Navone’s white cotton-covered XXL Ghost sofa, designed for the Italian company Gervasoni, hangs an eclectic arrangement of 1950s rattan mirrors. In his bathroom, a vintage dentist’s cabinet is filled with toothbrushes he was given by one of the great-grandchildren of a 19th-century tabletier — an artisan who made objects from bone, horn, mother-of-pearl and tortoiseshell — in the Oise region north of Paris.

Rozensztroch modestly talks about his belief in kindness, his desire to motivate people, to incite them to think differently about the things they live with. It’s a philosophy that verges on animism.

“For me, objects have a soul,” he says. “It sounds improbable, I know, but I fall a little bit in love with each object — its color, its shape, its feel, its material. I see these objects as a kind of family, as being related to each other, as talking to one another. Their monetary value doesn’t matter to me a bit, nor does so-called good taste. I just always know that somewhere there is another exceptional object out there waiting for me to find it, to adopt it, to give it a second existence. For me, creating this intimate world for myself is a way of life.”

Get the Look

PURCHASE THIS BOOK

or support your local bookstore