July 4, 2016Architect David Scott Parker has carved out a tripartite niche in historic preservation, top-end residential design and — through his gallery, Associated Artists — Aesthetic Movement antiques. Top: An open kitchen, family room and breakfast nook come together in a Parker-designed home in coastal Guilford, Connecticut. All photos by Durston Saylor

Most architects say they place program above all else — in other words, the design of their buildings serves its function and the clients’ needs, not the other way around. But not all architects actually follow through on this claim.

David Scott Parker is one who does. He has built some lovely structures that are discreetly ruthless in their devotion to program. That’s one reason why they don’t resemble each other. “In the age of branding, we don’t brand — we fit a client,” says the soft-spoken Parker, 55, who hung out his own shingle in 1989 and now has offices in New York City and the coastal Connecticut town of Southport. “You don’t come to us to get another client’s house. It’s specific to your needs, as well as to the setting and context.”

Parker largely tackles residential work with his team of 14 associates, but another, smaller piece of his practice is historic preservation. His ability to plumb the past for useful design is evident in the brand-new, chameleon-like carriage house he built in Weston, Connecticut, adjacent to a 1938 Colonial Revival–style home by the early-20th-century residential specialist Charles Cameron Clark.

Yes, the cross-gambrel cedar-shingle roof (with gabled dormers) and copper-roofed cupola belong to a 19th-century idiom, but the design addresses some very 21st-century needs, too. On the lower level, is a six-car garage; on the middle level, a poolhouse; on the upper level, a gym and den. (Parker also did a quiet expansion of the adjacent main house.)

“It’s based on a ‘bank barn,’ meaning that it’s built into the side of a hill,” says Parker. “The thing about a building like this is that has to be understood in its different functions from different perspectives — it evolves as you move around it.” Inside, the old beams and large stone hearth in the den give the structure a warm emotional center.

Parker used hand-planed timber beams and salvaged white-oak flooring to give some warm, casual character — and the patina of a much older house — to this new-build oceanside summer home in Rhode Island.

Parker built another shingle-style building in a very different part of New England, perched on Rhode Island’s rocky coast, not too far from the storied town of Newport. It’s 6,800 square feet, so the gambrel roof helps it appear less voluminous, while at the same time matching the vernacular of the region.

The clients’ primary brief here was to maximize the windswept views of the ocean, in particular from an octagonal pavilion Parker wanted to include in the scheme. “But they couldn’t decide whether they wanted it to be an inside or outside room,” he recalls. So he gave them both. “It’s an open pavilion, but it has windows on hydraulic lifts that rise from the basement. Now, it’s a four-seasons room — the best of both worlds.”

The interiors of the rest of the house follow a beach scheme, with a muted palette that recurs again and again in Parker’s projects. (The decor details are by Terry Crowley Interiors, of Vero Beach, Florida.)

Parker was raised in the famous utopian town of New Harmony, Indiana, which is still replete with pristine examples of 19th-century architecture (including all the revivals, from Greek to Romanesque to Gothic) in its large historic district. “I grew up as the town was being restored, and I worked on the restoration of buildings,” he says. “That’s always been an interest of mine.”

After undergraduate work at the University of Virginia and then a degree from the Harvard Graduate School of Design, Parker worked for Richard Meier (who coincidentally designed the Atheneum, the New Harmony visitors’ center), concentrating on the schematic design for the Getty Center in Los Angeles, one of the signature museums of the late 20th century. “Richard does amazing work,” says Parker. “There is a precision about his work and a consistency of detail — he is so thorough.”

“You don’t come to us to get another client’s house. It’s specific to your needs, as well as to the setting and context.”

In the Wrights’ Manhattan penthouse, Parker deployed a series of lenticular-glass-paneled metal sliding doors to allow the apartment to be divided up in myriad ways, obscuring views between rooms, while also letting light pass through the entire space.

Parker brought those same qualities to the Manhattan penthouse of Bob and Suzanne Wright. Bob was the president and CEO of NBC, and the couple are now all-star fundraisers for Autism Speaks. They live in a tall building on the West Side. “It overlooks Riverside Park, with three-hundred-and-sixty-degree views,” says Parker. “We have done four residences for them, all very different.”

In this case, the clients needed some healthy compartmentalizing. “They use the apartment for receptions and benefits,” says Parker, who had an ingenious solution to the problem of multiple functions: He added shoji-like screens made from lenticular glass.

“They’re movable, and they refract the light but obscure the view,” he says. “You can get privacy if you want, even though there are two hundred people there.” Interior designer Leslie Heiden established a neutral interior of soft grays, greens and wood trim to balance the hardness of metal and glass.

There was also need for a media room. (Given Bob’s profession, this was not a house where the TVs would be hidden.) To that end, Parker created a special limestone fireplace that surrounds and cossets the biggest TV in the house. “The flue goes up the side of the building, becoming part of the architecture,” he says. “You can see it from Riverside Park.” He adds with a chuckle, “We had to get that approved.”

Approvals are part and parcel of Parker’s historic-preservation work, and master planning is his specialty — advising on how and when to fix, restore and conserve grand old buildings and then carrying out those plans. For the Williamsburg Savings Bank — an 1875 George Post–designed Beaux-Arts masterpiece that’s a Brooklyn icon — Parker concentrated on bolstering its dome and repairing the lattice work around the windows. The landmarked exterior and interior hadn’t been altered, but they had been left to decay, so he helped the client turn the bank into an art gallery and events space. The original foyer, for example, became a bar.

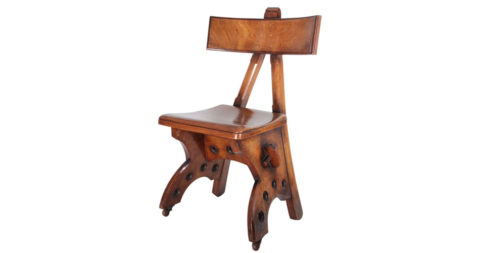

Located in Southport, Connecticut, Parker’s gallery deals in fine and rare examples of American and English Aesthetic Movement furniture, decorative objects and artworks. Its offerings include significant works by some of the movement’s most celebrated designers, among them Thomas Jeckyll, whose brass fireplace fender (in front of hutch, on floor at rear) matches one made for James McNeill Whistler‘s famed Peacock Room, in London.

The same feel for history helped Parker employ sleight of hand to restore and rebuild an Aesthetic Movement–style brownstone on Manhattan’s East 72nd Street, the only single-family home on the block. It had to be fully modernized but not look that way.

The home was completely rewired, with new HVAC systems, smart-house technology and an elevator added; at the same time, Parker painstakingly brought back period details like encaustic-tile floors and leaded-glass windows. Where details were beyond repair, he subtly and faithfully re-created them, as with the elaborate woodwork in the living room. “The clients really understood this era,” says Parker, and were thus happy to stick it out through the dozen-year project. (He also did a very different home for them in the Hamptons.)

The Aesthetic Movement is a Parker specialty, in fact, and his passion for it drives his other business, the Southport-based Associated Artists. The gallery specializes in late-19th- and early-20th-century furniture and decorative arts by the likes of Louis Comfort Tiffany. “John Ruskin talked about the importance of handcrafted pieces and honesty, and that’s our focus,” Parker says of the 100 or so items that are usually on hand at the gallery. “The attention to detail in these works has always attracted me.”

Typically, Parker has the long view in mind — the most interesting thing to him about the Aesthetic works is the clear path he says he can trace from that era (which can seem distant now) to the world of design today. And that keen perspective is what has driven his architecture, too. Admiring the surprisingly clean lines and often utilitarian qualities of his Associated Artists inventory, says Parker, “you can’t think of modernism coming into being without this era having occurred first.”