The new exhibition “Ed Ruscha and the Great American West,” at the de Young Museum in San Francisco, looks at the myriad ways that Ed Ruscha (above) has portrayed the western United States, especially in his prints and photographs (portrait by Kate Simon). Top: Ruscha’s 1962 black-and-white photo Standard Station, Amarillo, Texas led to his famed painting and screen-prints on the same theme (Whitney Museum of American Art). All artworks © Ed Ruscha

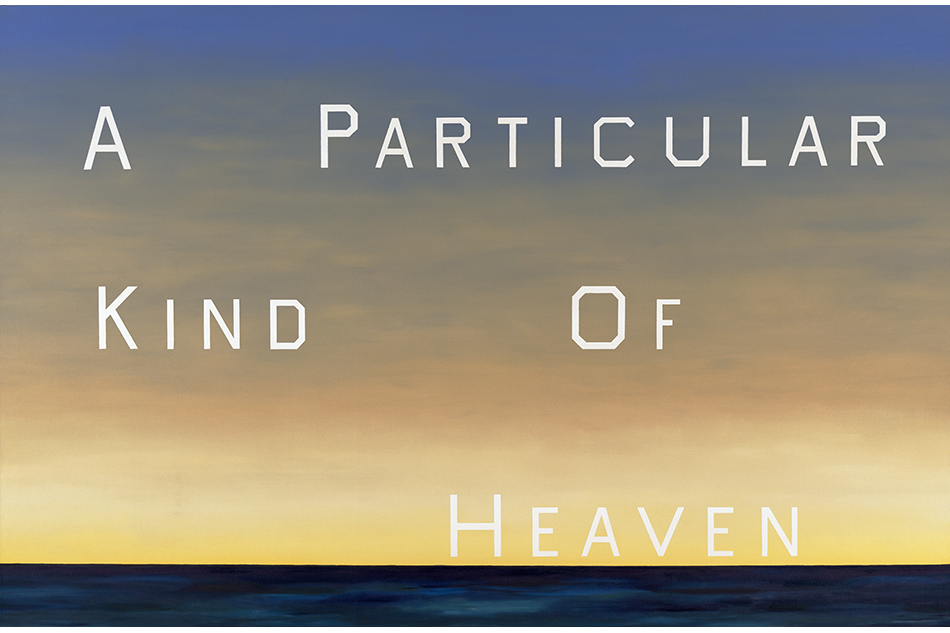

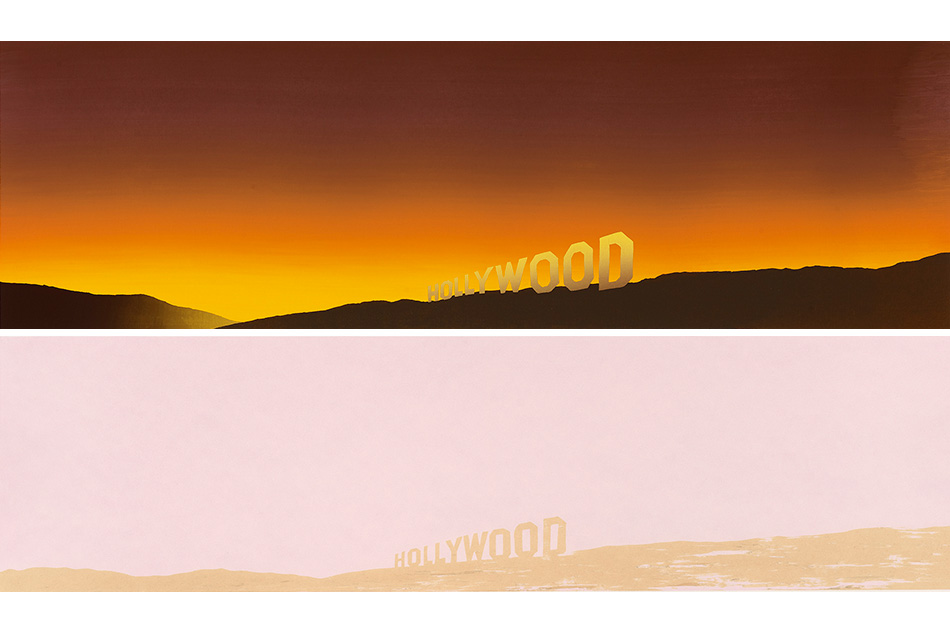

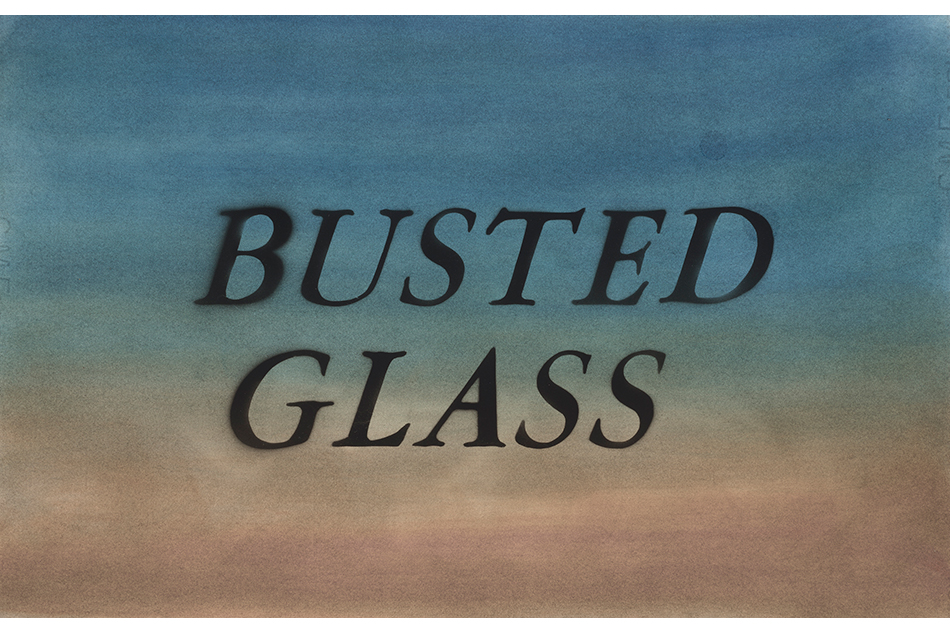

Ed Ruscha’s art is both familiar and uncanny: hyper-real, foreshortened cinematic perspectives of such sites as the Hollywood sign spied from his first Los Angeles studio and gas stations and billboards viewed from cars cruising across the American Southwest.

And Ruscha’s story can sound like a movie dream: Oklahoma-reared teenager drives along Route 66, à la Jack Kerouac, heading to art school in the cultural backwater of late-1950s L.A. Toss in remarkably long-lasting good looks, extraordinary talent and a few starlets and Hollywood pals along the way, and you end up with an appropriately filmic cliché.

San Francisco’s de Young Museum and Karin Breuer, chief curator of graphic arts at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, have organized a new retrospective centered on Ruscha’s robust printmaking practice titled “Ed Ruscha and the Great American West.” Breuer’s goal was to present a more nuanced picture of the American West than the stereotypical one of cowboys and canyons by looking at it through the work of a major American contemporary artist who focused on the region. “I wanted to turn that idea on its ear by featuring a sophisticated artist who’s built a blue-chip career with a provocative and smart take on a locale,” she says.

In person, Ruscha seems less aloof and inscrutable — his press persona — than thoughtful and clearly dedicated to his work. No instant star, he earned his place in the art-historical pantheon through discipline, skill and a tenacious will to venture into whatever the heck intrigued him, long before conceptualism sanctioned such inquiry. What intrigues him to this day is the fact versus the myth of Western expansion, the region’s pioneering individualism in all areas (mass media, language, typography, urban sprawl) and the solace nature offers (while it lasts).

Coyote, 1989, a lithograph published by the artist. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

On view through October 9, the de Young show explores these themes through a core of prints from the museum’s archive of Ruscha’s graphic oeuvre, complemented by paintings, books, films and drawings lent by major collections, including the Getty, the Whitney and the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo. The 99 works, hung with elegant airiness by Breuer, convey Ruscha’s astute take on an incongruous place, where scenes of unspoiled natural beauty (snowy peaks, deserts, seas and sunsets) coexist with vulgar shopping malls; where charming, rough-and-tumble, no-airs authenticity sits beside a media-philia that considers bling way cooler than the Sunday Book Review — and no one cares because here you live and let live.

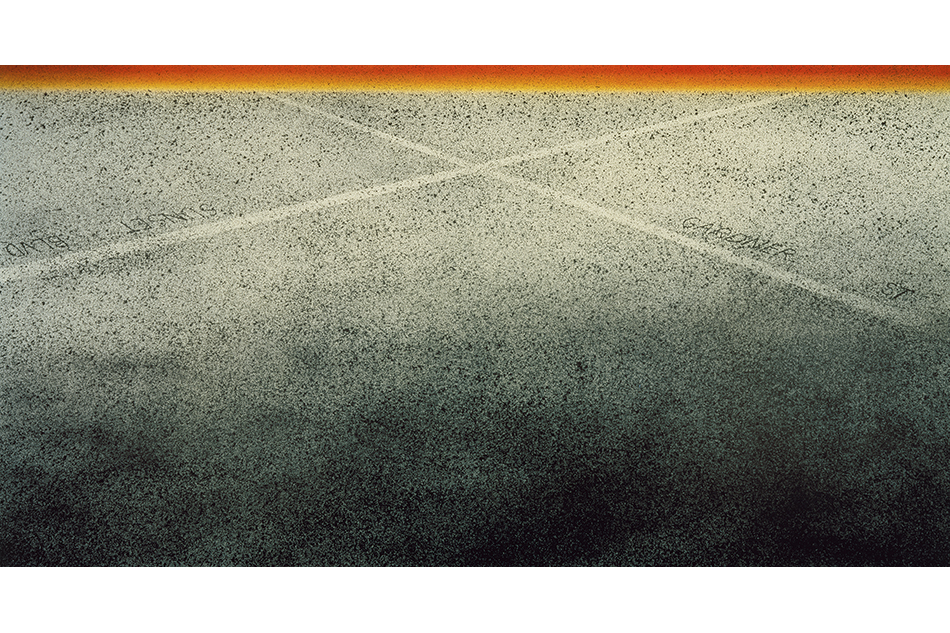

Whether through caricatured peaks written over with the names of clogged L.A. thoroughfares or glowing Pacific horizons whose utopian vision has been defaced with out-of-place phrases, Ruscha has spent 50-plus years capturing the West in images that blend high Pop with the Kantian sublime.

Ruscha spoke to Introspective from his studio in Culver City.

Did the theme for this show come from you?

No, the whole project came from Karin Breuer, but I do think she is responding to an obvious constant in my work. I believe in the America of the West, which is what fuels my work. I traveled throughout the West in my youth, and it has a particular kind of natural beauty I have an affinity for.

Noose Around Your Neck, 2001, a photogravure with screen-printing, from the ”Country Cityscapes” series published by Graphicstudio at at University of South Florida, Tampa. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

You have a home, where you go to recharge, in the fairly unspoiled California desert area of Joshua Tree. Do you lament a fading West?

The West is complex, not one thing. From early in my life, I got intrigued by the expeditions of Lewis and Clark, and I studied their exploits and travels historically. Eventually, I got to see aerial photos of their path, and, well, it is a little frightening, because that unspoiled land feels so unreal now, everything is so developed. Progress is inevitable, so I am not rejecting it necessarily. But when you consider that kind of acceleration, it shakes you to your core.

Still, your work never feels nostalgic.

When I came out to go to college, I think Route 66 was two lanes, if that. The whole place was in a very quaint state, and that persists for me. I sort of still live in versions of that black-and-white world.

You came to the West when you were a teen. Was that the beginning?

Our family drove through L.A. and Hollywood, headed to my grandparents, who lived among the big Sequoias. Just the diversity and beauty of it all had a great impact on me. Still does. There was something about the vegetation and the mood of the place. Palm trees still have this seductive power for me visually.

Pool #7, 1968, from the ”Pools” photo series published in 1997 by Patrick Painter Editions. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

In Oklahoma, there could not have been a lot of handsome, heterosexual men who wanted to be artists.

My mother always encouraged us to engage in art. She enrolled me in this painting class that was a little clumsy and new for me. At the same time, I was aware of another aspect of art: cartoons and newspaper comics. These offered another view of visual communication.

So that was the start of it all — the Sunday funnies?

Actually, it started by accident. I worked for an industrial-supply firm in high school. They sent me to the library to go through the phone book — no computers then, all hands-on — to gather names of every lumber company. Out of pure curiosity, I wandered through different rooms of the library. I started to look at books on design, works from the different art periods. I looked at Surrealism, Dada, studied all the major modern-art movements.

Gas, 1962, a lithograph published by the artist. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

That is interesting because your art is elegant but accessible, even populist.

What has formed me comes from a variety of odd sources. I was also getting aware of the whole Dust Bowl era through photos. I got interested in the plight of the people in the Mid- and Southwest as captured by Walker Evans. Those were people who shared the sensibility of the people where I came from.

That, to me, wasn’t all sadness. It was a Bonnie-and-Clyde kind of time, a very honest angle to it. So all of it — cartoons, that whole pioneer spirit — it all attracted me and still does. You add to that my general wanderlust, and that was that. I applied to art school, got a few options, but I knew that I wanted to head toward the Pacific.

Did you have a major in mind?

Oddly enough, I thought I’d become a sign painter. As a student, I painted things like Coke bottles and burgers — it was called sho’ card art, which referred to one-stroke hand-painted lettering and signage.

And you went to the Chouinard Art Institute, now CalArts.

This terrific lady Nellie Chouinard, who was ninety-five years old and started the school in 1921, came in every day to see that things were running smoothly. Her friend was Walt Disney, so he put money into the school, changed the location and thought it would be good to train possible future animators there. Soon as my dad heard Walt Disney was involved, he approved.

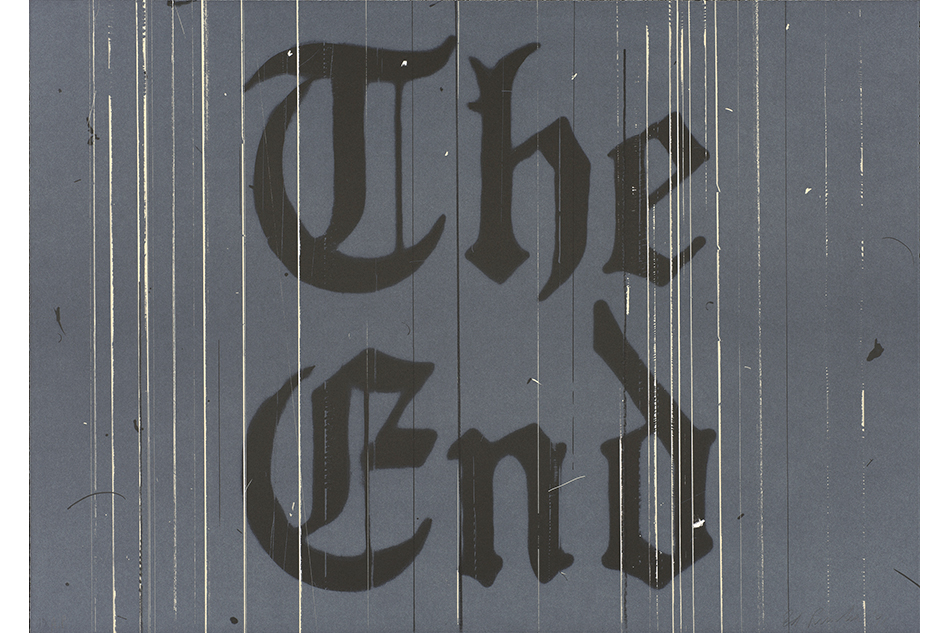

A detail of The Absolute End, 1982, dry pigment on paper. The Robert A. Rowan Collection

So with this goal of sign painting — that is almost comedic at this point —what did you actually study?

We had to take everything — drawing, painting, advertising. I took typography, which was really interesting, even sculpture.

Schools back then were not teaching the sort of art you’ve become renowned for.

True. There was a very romantic story coming down the pike that involved Abstract Expressionism. We were taught things like confronting the blank canvas and avoiding symmetry because it was boring. I stuck to what made sense to me, and things started to come around in my direction in the sixties, with the advent of Pop.

Any important mentors?

The truth is that there were amazing teachers, but I learned as much from the stimulating people I studied with, like Joe Goode. There was this healthy competition and lively chemistry that led us to search our own path. We inspired each other, and there was this healthy, vibrant competition to explore everything. As I moved along, I started to see that all art styles are related, each subsequent movement is inevitable, and each idea comes from the ones prior to it. After art school, I started to see that all art is a kind of historical and personal record, a diary of what interests each artist. So my work is a bit like a diary and a diuretic — ha, ha, ha.