March 16, 2015On a bright, cold January morning, Elliott Barnes sits at a large table in his offices near Les Halles on Paris’s Right Bank. Crisp winter sunshine streams in the windows of the enfilade of rooms that make up his architecture and design studio, Elliott Barnes Interiors (EBI). It’s the weekend, and the offices are quiet. Barnes is dressed in a casual yet elegant knit turtleneck. At one end of the table are the makings of several design presentations — fabric and material samples laid out in groups. “Just a few of the projects we are currently working on,” says Barnes, who returned late the night before from Los Angeles.

Barnes is the quintessential American in Paris. Born and raised in L.A., he studied architecture and urban planning at Cornell before making his way to France in his early 20s. In 1987, Barnes landed a career-defining job, working for legendary French designer Andrée Putman in her Paris studio. “She was a very strong lady, and I appreciate strong women,” Barnes says. “She was a great boss. We had real respect for her — and we got that back in wonderful ways.”

Barnes initially began working as a project designer for Écart International, the company Putman established with a collection of re-issued furnishings by such early-20th-century designers as Jean-Michel Frank, Eileen Gray and Pierre Chareau, and which eventually grew to include her own furniture and interior design projects.

In 1997, Putman sold Écart, and, finding herself at a crossroads, decided to establish her eponymous firm. “We essentially had to start over,” Barnes recalls. “We had very small offices. Sunday meetings would take place at her home. She would make omelets and a great frisée salad for the team or serve caviar and vodka — and we would work. It was great. Then, of course, it really took off.”

By the early 2000s, Barnes found himself at his own career crossroads, feeling the moment had come to open the offices of EBI. The strength of Barnes’s idiosyncratic style — pared-down spaces bordering on minimalist, yet enlivened by subtle interplays of texture — quickly gained him recognition. One French design critic described Barnes’s work early on as “textured minimalism.”

“I think that hits it,” he agrees today, adding that he likes to think his work is always intuitive, every project informed by its own unique qualities.

In the 10 years since establishing his firm, his projects have ranged from high-end residences in Paris, Tokyo, Bangkok, Vienna, Cannes, Dublin and Geneva to a Ritz-Carlton hotel in Germany, shops, institutional spaces and the renovation of legendary Paris Jazz club Duc des Lombards. Upcoming Parisian projects include a 45-room boutique hotel for a private investor in a Haussmanian building in the 16th Arrondissement — a place “for the ‘citoyen du monde,’ for the initiated,” says Barnes, “for those who are free and at ease in any city.” As for a new Paris restaurant near the Bourse for the American culinary sensation Daniel Rose, he says it will be a “rigorously French place.”

“What I took away from my experience with Andrée is that there is always a solution. A small detail can make a huge difference. And when you know that you are never stuck.”

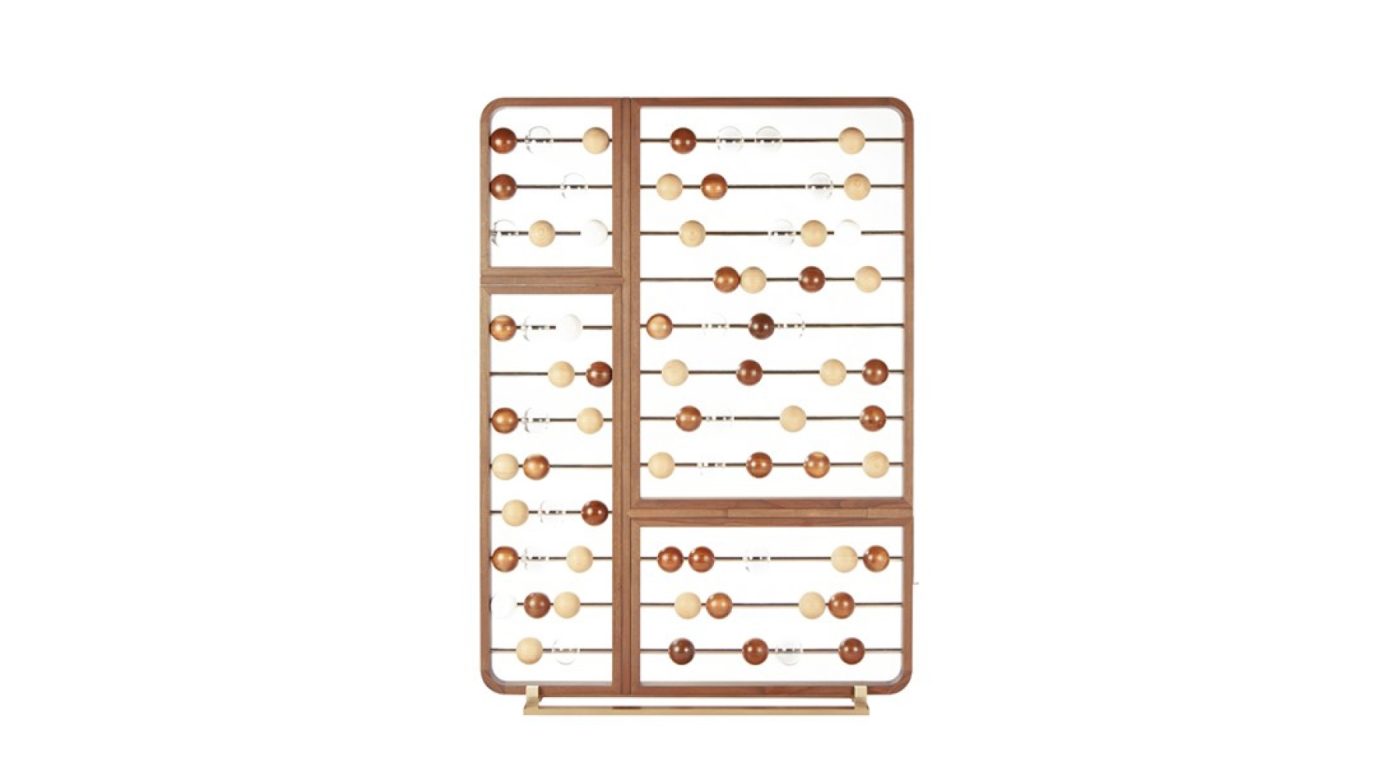

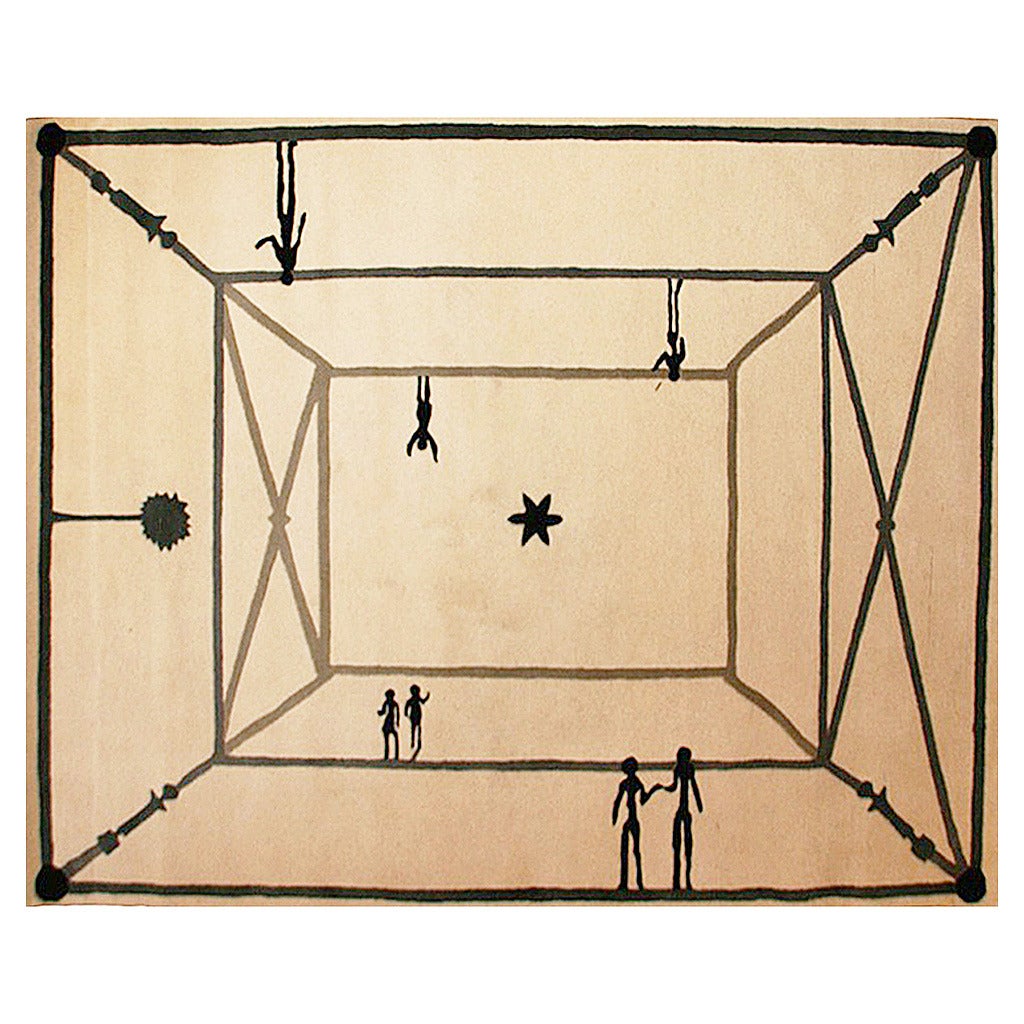

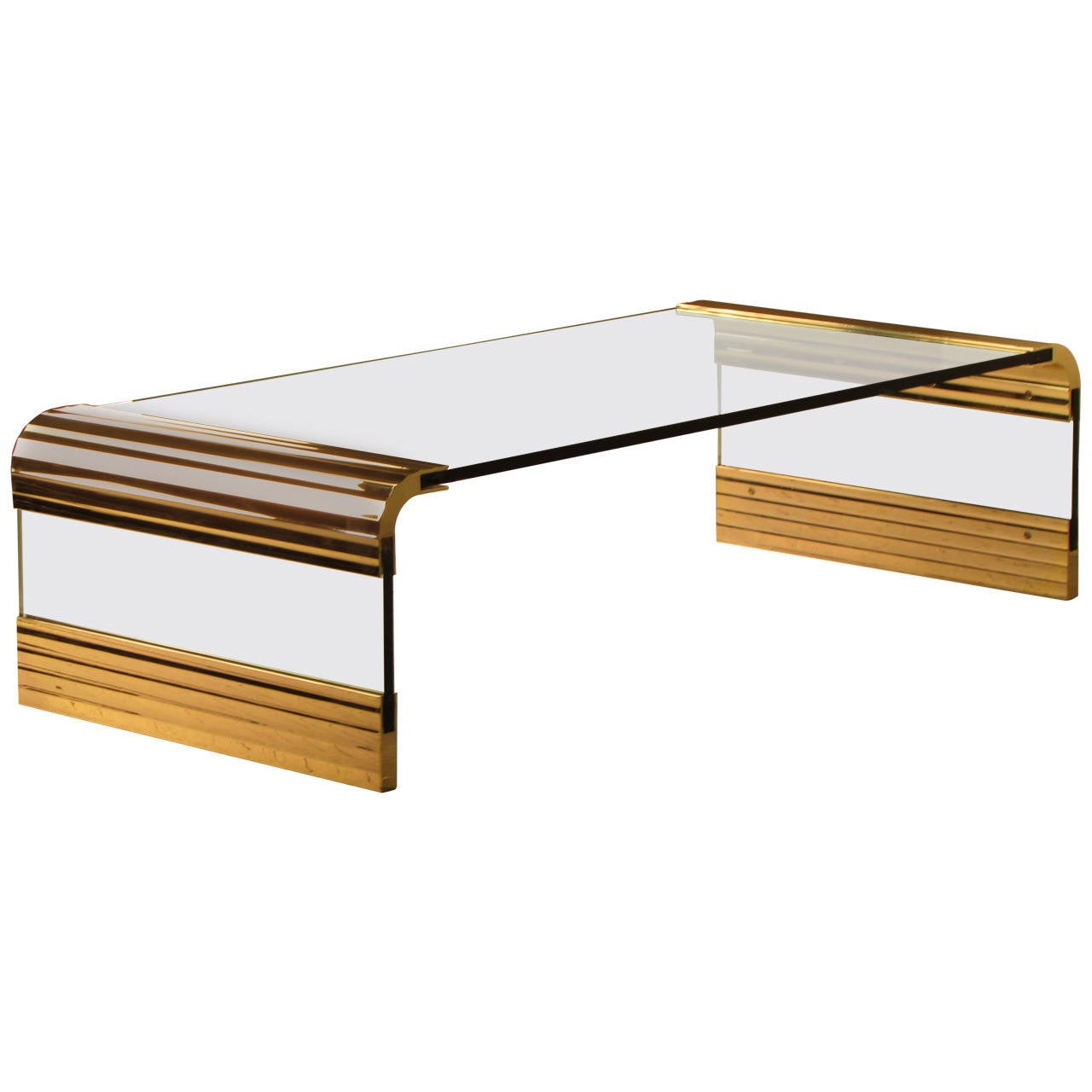

Barnes’s furniture designs include seating for Écart (now owned by Ralph Pucci) as well as a recent collaboration with manufacturer Philippe Hurel. Titled “Une Après-midi de Paresse” (“A Lazy Afternoon”), the collection plays on themes of relaxation, the passage of time and pleasure. Pieces include an hourglass-shaped stool, a standing mirror triptych, an abacus-inspired screen and an oversized daybed in oak with hidden drawers, covered in leather, that slide open to reveal cases in pear burlwood. The upholstery is a mixture of velour and cotton with an abundance of pillows in satin, wool and cotton.

“I think what I took away from my experience with Andrée is that there is always a solution,” says Barnes, whose talent has been lauded by AD France, among other publications. “A small detail can make a huge difference. And when you know that you are never stuck.”

“Every project always begins with free-association ideas,” he continues, “and it can be totally off the wall.”

One example is his design for the Ruinart Champagne headquarters in Reims, northeast of Paris. He incorporated materials found on the site, including local stone, wood from wine cases and glass from wine bottles, which he turned into a terrazzo floor. “We even managed to make wallpaper from grape peels,” says Barnes. “What I really enjoy is connecting a project to the place.”

For a Paris loft-style apartment spread across the top three floors of a Right Bank building overlooking the Seine, meanwhile, both the views and the client’s frequent travels to the Far East informed the design, which abandoned completely the traditional Parisian apartment footprint. “We created a layout where there is no real destination space,” explains Barnes. The elegant, almost empty interiors create a harmonious flow from one room to the next. “You can sleep wherever you want, eat where you want. What is important are the perspectives, light and volumes,” explains Barnes. “I think that corresponds to our lives today.”

Another high-end Paris residence was conceived for clients with an important art collection — and three small children. Barnes maximized light by replacing dividing walls with glass partitions. The subtle gray-white palette throughout leaves nothing to distract from the art, which he integrated into the scheme so that it lives seamlessly amongst the activities of the family. He then punctuated the three-floor space with a sculptural staircase made of twisting blackened steel that is, itself, as dramatic as a piece of art.

“You’ve got to let your project be what it wants to be — push things around a little bit to see where it wants to go,” explains Barnes. “Projects have lives, they have their own dynamic, I see my role as helping these things push themselves along.”

That the American-born designer would end up living and working abroad makes perfect sense. When Barnes was a child, his father, a doctor, served as the head of the Los Angeles County Public Health Department. He landed a job in the Middle East when Barnes was four – and, anticipating that they would send their son to a Swiss boarding school, Barnes’s parents enrolled him at the Lycée Français de Los Angeles. Ultimately, his father did not go abroad, but Barnes remained at the French school for 10 years. “From a young age, I was comfortable in an international context because my friends were Swiss, Italian, Iranian, Iraqi, African,” he recalls. “Even as a kid, I always wanted to move to Europe.”

Now a Paris resident for nearly 30 years, Barnes says he is newly fascinated with his hometown. “I’ve got my eyes on L.A.,” he explains. “I find there is a really interesting energy there right now.”

Going from his Paris offices on the Right Bank and walking over the Seine to the Left, Barnes says he feels an unlikely connection between his adopted city and hometown.

“As you come out of the Louvre crossing the Pont des Arts footbridge — if you look to the left and then right — you suddenly have this huge expansion of space. It’s that same notion of space that I love so much about L.A.”