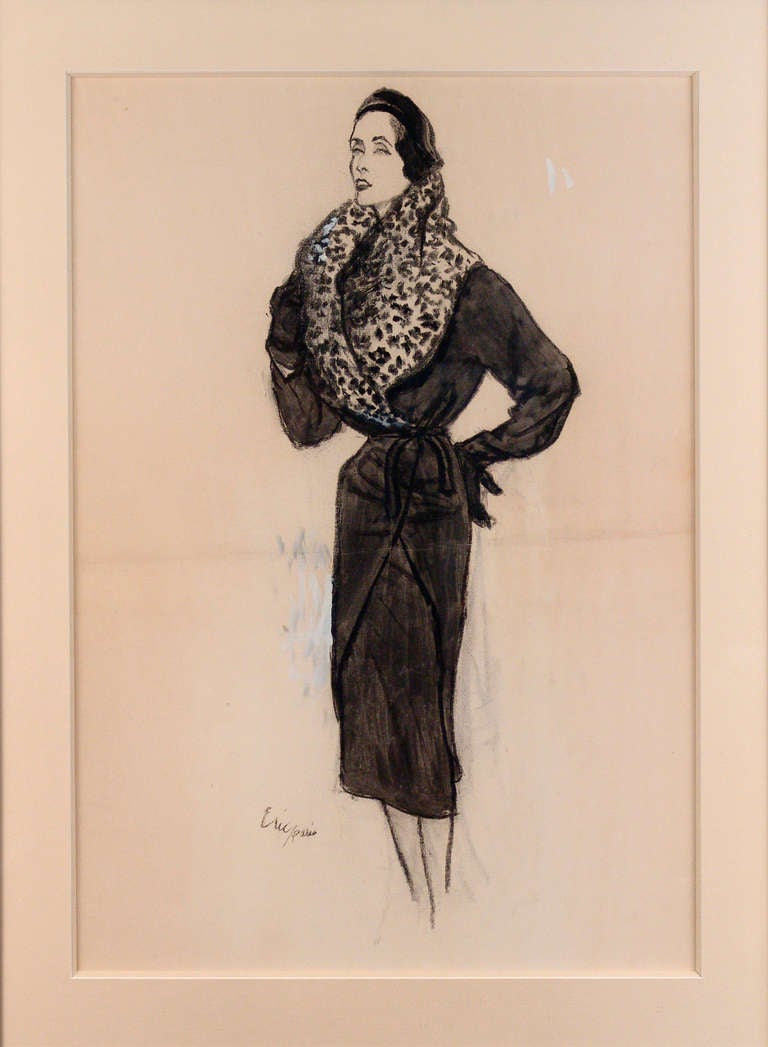

January 26, 2015Elsa Schiaparelli seen here in an undated photograph in her Paris library, which she adorned with tapestries by Boucher. Where the pieces weren’t wide enough to cover the wall, she convinced her friend Jean-Michel Frank to fill in the intervening wall space (photo courtesy of Meryle Secrest). Top: Two pieces designed by Jean Cocteau in collaboration with Schiaparelli (photo courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art).

Back at the start of the 1930s, when the New Yorker’s Paris correspondent, Janet Flanner, described Elsa Schiaparelli as the new “comet” zooming into the French fashion firmament, she might have been looking into a crystal ball. The wildly original and innovative clothes of the Italian-born couturier made her arguably the most influential Paris designer of the ensuing decade. Schiaparelli’s private clientele included such self-confident trendsetters as American heiresses Daisy Fellowes and Millicent Rogers, the Duchess of Windsor and a bold-faced slate of Hollywood names from Greta Garbo and Marlene Dietrich to Katharine Hepburn, Vivien Leigh and Lauren Bacall. Couture triumphs were accompanied by the unparalleled renown and exceptional financial rewards of her licensing agreements with American department stores — from sportswear to evening dresses to (yes, even) housewares. Her achievements propelled her onto the cover of Time magazine in 1934.

Little more than a decade later, when fashion moved on with Dior’s New Look in 1947, Schiaparelli’s once instinctive grasp of the American market faltered. Her business crashed in 1954 (just as Coco Chanel, her archrival in the early days, who’d then fallen by the wayside, began her comeback). Schiaparelli vanished, leaving only the lingering fragrance of her famous perfume, Shocking, in her wake. Now Elsa Schiaparelli, a revealing biography by Meryle Secrest, looks meticulously at this onetime empress of French fashion and makes a compelling case for reassessing not only Schiaparelli’s place in fashion history but her influence as an artist.

The American socialite Wallis Simpson included the designer’s white silk organdy evening gown, complete with lobster, in her trousseau for her marriage to the Duke of Windsor in 1937. Photo courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art

Dazzle and daring were bywords of Schiap (her self-annointed nickname). She combined such singular hues as her signature “shocking pink” with purple; red with hyacinth; or deep blue with orange in a tweed number deemed “thrilling” by Harper’s Bazaar in 1932. The designer introduced such firsts as the trompe-l’oeil sweater (where a white bow-knot neck was knitted into the otherwise black pattern). It became a hit in America and led the way for other stateside successes: the patented swimsuit with built-in bra, the culotte skirt, the wrap dress (long before DVF) and evening jackets to match gowns or team with palazzo pants. Schiap also trailblazed the use of avant-garde fabrics, made detachable ornaments such as pockets that looked like purses and purses that looked like pockets, and designed reversible coats.

In her new book, Secrest offers insights aplenty into the strategist that lay behind the “madcap” Schiap façade. Invited to a smart ladies’ luncheon that included some important American department-store buyers, the designer wore the bow-knot sweater. “One can imagine her plotting her debut with all the surprise and cunning of Napoleon,” Secrest writes. “Perhaps, she waited to arrive until everyone was seated, for maximum effect. She was a sensation…After the lunch, Schiaparelli was besieged with guests who wanted a sweater just like hers. But she was saving that information for the New York buyer of Abraham & Straus…who wanted forty sweaters exactly like that one.”

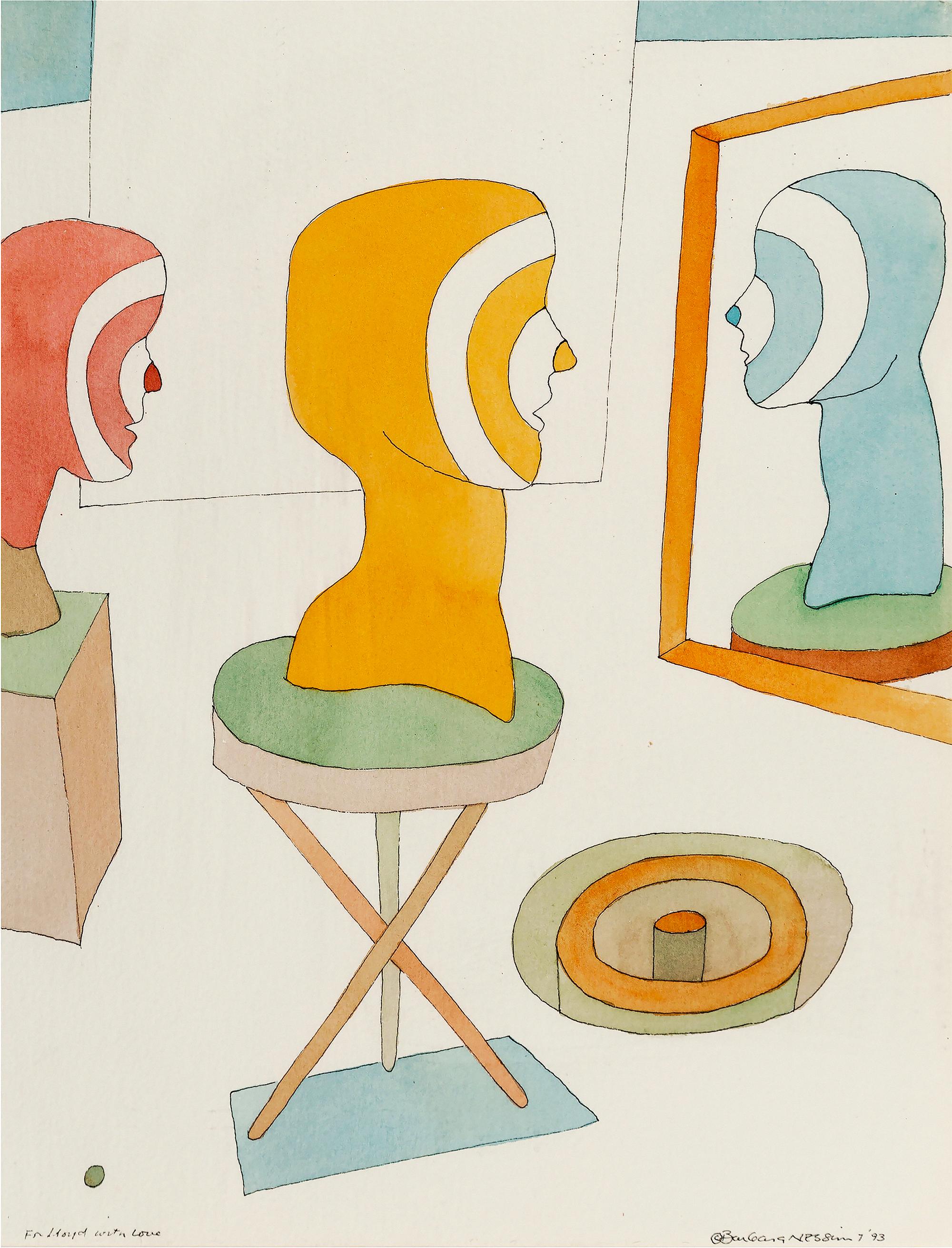

Color photographs and drawings illustrate Schiap’s “lobster” gown (a collaboration with Salvador Dalí), her “insect” necklace and her evening coats and jackets — one featuring Jean Cocteau’s optical illusions, others bejeweled, Lesage-embroidered or gold-braided. More photos show us Schiap wistful at age 4; alone in her Place Vendome boutique at the peak of her success; with Dalí at a smart outdoor gathering; and, later in life, with her beautiful granddaughters Berry and Marisa Berenson.

“I think she was a genius,” contends Secrest, who knows a thing or two about the subject, having penned biographies of such legendary figures as Amedeo Modigliani, Frank Lloyd Wright, Joseph Duveen, Stephen Sondheim, Bernard Berenson and Salvador Dalí. In an interview squeezed in between a series of enthusiastically attended lectures in the U.S. and England, Secrest tells 1stdibs’ Jean Bond Rafferty why she chose the fashion designer as a subject and why she thinks the time is ripe for a Schiaparelli revival.

“The success of the Schiaparelli-Dalí collaboration,” writes Secrest of the duo, seen here in 1949, “hinged upon Schiaparelli’s ability to transform what were bizarre, even macabre, ideas into wearable, flattering garments.” Photo courtesy of Meryle Secrest

1. Beginning with American portraitist Romaine Brooks, you have written 11 successful biographies, mainly on art-world personalities. This is your first on a fashion designer. What is the secret of finding the right biographical subject, and what made you choose Schiaparelli?

To do a biography, there has to be a connection to the subject. Some fashion writers don’t understand why I should be writing about fashion at all. But I’ve always been intensely interested in it, designing clothes at age 12 and making my own at 14. Yes, the work is essential, but you can’t look at the work without knowing who the person is and showing how the work relates to the life. I was interested in Schiaparelli as a Surrealist dress designer. In my view, there is a direct link between fashion and art, so close as to be indistinguishable. Fashion relates to sculpture, and Vogue made references to Schiaparelli’s sculptural sense in the 1930s. Incidentally, she thought of herself as a sculptor.

2. Schiaparelli worked with Jean Cocteau, Alberto Giacometti and Man Ray, but Dalí stands out as her most influential collaborator. His Surrealist spirit seems to romp through her collections called Music, Zodiac, Circus and Commedia d’Arte. How important was he?

It was a two-way street. There are things that happened in Dalí ’s life that show up in her clothes, and things that happened in her life that show up in Dalí’s ideas. She tells one story in her memoir, Shocking Life, published in 1954, about how when she was a little girl she had the feeling that she was ugly so she planted seeds in her ears, nose and mouth to grow beautiful flowers that would hide her face. I looked at that anecdote for a long time before I decided that it probably did happen. When the first Surrealist exhibition was held in London in 1936, the papers grabbed onto Dalí’s promotion and guess what? It was a woman walking around Trafalgar Square with a face full of flowers. He inspired the Lobster and Skeleton dresses and the difficult-to-carry-off Shoe Hat — only Gala Dalí, Daisy Fellowes and Schiaparelli wore it. She was so much cleverer than the other couturiers with her Surrealist buttons, which she invented with Dalí. “OK, let’s have acrobats, butterflies, radishes, carrots, dollar signs and seashells,” she decided. Dalí’s fascination with Mae West — he painted her face like a living room [Face of Mae West Which May Be Used as an Apartment, 1935] — showed up when Schiaparelli launched her Shocking perfume in 1937. The bottle was modeled on Mae West’s nude torso. And the top was covered with porcelain flowers.

When she was a little girl she had the feeling that she was ugly so she planted seeds in her ears, nose and mouth to grow beautiful flowers that would hide her face.

Gala Dalí, wife of the artist, wore this magenta velvet evening jacket embroidered with metal threads to the opening of New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1939. Photo courtesy of Meryle Secrest

3. Her husband, William de Wendt de Kerlor, proved to be more charlatan than count, and you unmask the identity of her Scottish beau, hitherto only known as “Peter,” who underwrote her London successes. How did you track down new truths about her private life?

When I began to investigate her life, I realized no one had actually studied it. She went from a very strange, doomed marriage and poverty in Greenwich Village to fame and fortune, wild London adventures and dark suspicions vis-à-vis her movements during World War II. It has been repeated ad nauseam that her husband was a Polish count and that she was a countess. All that comes from her daughter, Gogo, and nobody bothered to check it out. You know, people don’t dig. In her memoir, which is very unreliable, she doesn’t even mention his name. Along with his identity, government reports show that he was convicted of illegal fortune-telling, and she and her husband were deported from England in 1915.

Finding “Peter” was a riot. I looked at every single name I could find in her business and private worlds and there was no Peter! We finally figured out it was Henry Horne, whose nephew, Sir Alistair Horne, wrote a book called A Bundle from Britain, in which he talked about Schiaparelli. He told me Henry Horne was known as “Wicked Uncle Henry” because he made fortunes, then lost them and had to be bailed out. This was the guy that Schiaparelli chose not only to love but to put in charge of all her money! He had a controlling interest in her perfume, used it as collateral for something else, and it crashed.

Schiap arrives on the Pan Am Clipper in New York, in 1941. Her unusual freedom of movement during the first two years of World War II has prompted speculation that she was a spy for the German government. Photo courtesy of Meryle Secrest

4. In the chapter, “The Collabo,” you raise questions about Schiaparelli’s wartime activities. Some reviewers take this to mean she was a German spy. But Paris fashion designers who were trying to keep their businesses going were all more or less deemed to be “collaborating.” Few were prosecuted. What was the evidence?

She was supposedly working for the Red Cross in New York, but she was actually going back and forth in and out of France for two years after the German takeover. How did she do it? That is the biggest issue. A real dossier that I got through the Freedom of Information Act showed that the FBI followed her month by month for three or four years. In 1945, France was bankrupt and needed exports. Luxury couture was readily exportable. Schiap was one of the designers of Christian Bérard’s Théâtre de la Mode that traveled across the United States to promote French fashion. The French turned a blind eye to her, and others’, collaboration.

5. There has been a hiccup in the relaunch of Schiaparelli couture with the dismissal of designer Marco Zanini. But the search for his replacement continues. Is Schiaparelli too madcap for the 21st century, or is it time for a revival?

Even the Dalí designs were beautifully made, wearable and flattering. Take one special outfit of wide-legged pants in brown corduroy velvet and a short, pastel leaf-green tweed jacket with marvelous gold braid. You could wear it tomorrow. And its date? 1935. From my daughter and daughter-in-law, who are in their 40s, to the reaction at my lectures at the Fashion Institute of Technology, in New York, and the V&A, in London, nobody is saying her clothes look dated. I am on not exactly a crusade, but an endeavor, to re-establish her reputation. Since Schiaparelli was more famous than Chanel before World War II, it seems odd that we know Chanel’s life almost by heart and so little about hers. I have never felt that Chanel was as original or as adventurous. Schiaparelli isn’t just a dress designer; her work goes past that into art itself.