The late Iranian artist Farideh Lashai‘s ethereal yet provocative works are the subject of a new retrospective at Sharjah Art Foundation (portrait by Estate of Farideh Lashai). Top: The show is installed in a repurposed 19th-century home in the city’s heritage district. Photos courtesy of Sharjah Art Foundation, unless otherwise noted

Last November, the art world buzzed with news of a tantalizing exhibition at the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art. Called “Farideh Lashai: Towards the Ineffable,” it juxtaposed works by one of Iran’s most highly regarded female artists with largely unseen pieces by some of the predominantly Western artists who’d influenced and inspired her, from Impressionists like Monet and Pissarro to modern masters like Pollock, Giacometti and Rothko. Curated by Germano Celant, director of Milan’s Prada Foundation, and the Iranian architect and curator Faryar Javaherian, the show excited tremendous curiosity, mostly because of those mysterious masterworks. Part of the country’s legendary state collection, valued by some at $3 billion, they had been acquired by Iran under the guidance of Empress Farah Diba Pahlavi, who was forced into exile by the 1979 Iranian Revolution.

The exhibition’s real purpose, though, was to offer an overdue assessment of Lashai’s oeuvre. Before her death from cancer in 2013, at 68, she lived between Europe and Tehran. She is best known in New York for multimedia installations made in the last decade or so of her life — video projections on painted canvases rich with allusions to Persian folklore, literature, Western art history, pop culture and political conflict. Also on view in the TMOCA show were her lush, gestural landscape paintings and portraits, as well as glass and bronze sculptures and vases carved with plant forms. The latter were made in the 1960s, when Lashai was a crystal designer at Austria’s Riedel. Showing these pieces alongside paintings by other artists, which included works by the great Iranian abstractionist Sohrab Sepehri (1928–80), the display offered a key to Lashai’s aesthetic development over the years.

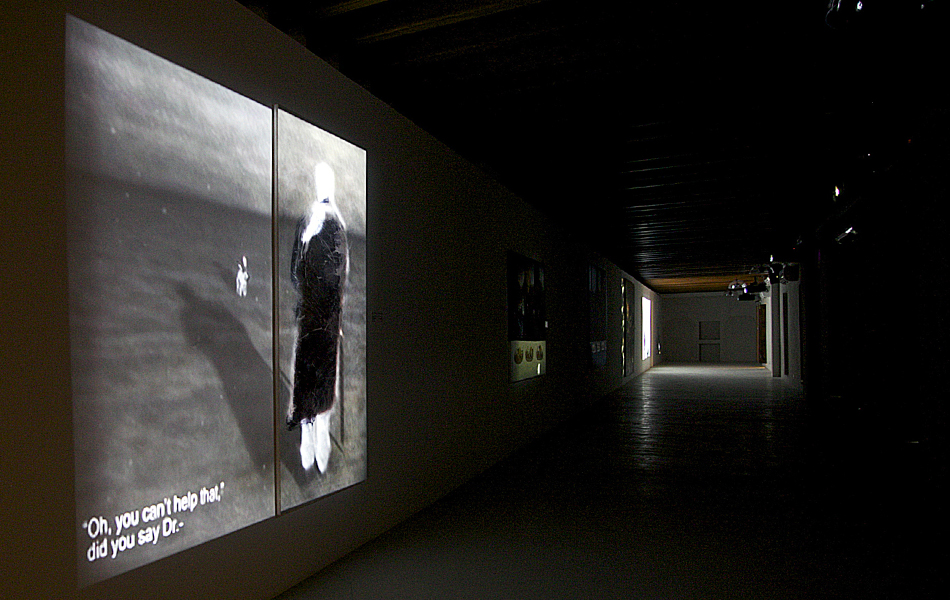

A visitor to the Sharjah Art Foundation takes in one of Lashai’s multimedia works, which often incorporate video projections on painted canvases.

“This was the first solo show for a woman in this museum,” says the Tehran-born, New York– and Dubai-based gallerist Leila Heller, who first showed Lashai in New York in 2008. “And in this male-dominated regime, it shows her importance.”

Now Lashai’s work, with additional loans from Paris’s Centre Pompidou, is the focus of “Farideh Lashai,” a new exhibition on view through May 14 in Sharjah, in the United Arab Emirates, where it’s displayed quite differently, in a 19th-century house in the capital city’s heritage district. Many of the video works are installed in rooms with wood-slat ceilings, among them Prelude to Alice in Wonderland (2011–12), which is drawn from a series based on Lewis Carroll’s tale and depicts animated rabbits, representing the Iranian people, both plucky and meek, gamboling through an abstract jungle to the heartrending strains of a Chopin Nocturne. Another multimedia work, Tyranny of Autumn, Not Every Tree Can Bear (2004), stands in a darkened courtyard; comprising cyprus leaves painted on Plexiglas and shimmering within wire-mesh cylinders, it suggests trees in a futuristic Persian garden.

“The context here is beautiful,” says the New York dealer Edward Tyler Nahem, whose gallery, like Heller’s, works with Lashai’s estate. “The art and the space are so compatible, like they’re hand in glove.”

The show was curated by Sharjah Art Foundation director Sheikha Hoor Al Qasimi, who explains that Lashai’s body of work is unusual because it evolved from pure painting to multimedia, and because she used “popular stories to subtly talk about politics.” After Lashai’s death, al Qasimi adds, she felt “it was important to have a retrospective that would show its diversity.”

Lashai’s canvases line a hallway of Bait Al Serkal, once the residence of the British Commissioner for the Arabian Gulf and now a crucial venue for the city’s burgeoning arts scene.

Born in 1944 to a political family in Rasht, on the Caspian Sea, Lashai painted avidly as a child. She studied literature in Germany, becoming enthralled with Bertholt Brecht (whose plays she later translated into Farsi), and worked at Riedel and Germany’s Rosenthal Studios before returning in the early 1970s to Tehran, then a cosmopolitan capital. She had several painting shows before tragedy struck: Although she wasn’t especially political, her older brother was active against the shah. Found guilty by association, she was imprisoned for two years.

After her 1976 release, Lashai continued living primarily in Iran. Yet the experience stayed with her, even after the Revolution. “She was not a communist or socialist — she was a humanist,” says Maneli Keykavoussi, her daughter, who runs the Farideh Lashai Foundation. “But once you have a past, they can always bring it up.”

Lashai’s work expresses that permanent cloud. Hedayat (2008), a portrait of the modernist writer Sadegh Hedayat (whose work was banned in Iran and who killed himself in 1951), bears bloody streaks. And her masterwork — and final piece — When I Count, There Are Only You . . . But When I Look, There Is Only a Shadow (2012-13), is based on Goya‘s print series “Disasters of War” (1810–20). When I Count comprises 80 photo-intaglio prints with Goya’s tortured figures stripped out; as a floating ball of light passes over them, suggesting both an ominous searchlight and a Weimar cabaret, they reappear, as if in a surrealistic nightmare.

“The figures are already brutal in what they depict,” says Lisa Fischman, director of the Davis Museum at Wellesley College, which showed the piece last fall, “but with the grace and mastery of Goya’s hand replaced, they become even more brutal.”

Hedayat, 2008, portrays the Iranian poet Sadegh Hedayat, whose work was banned in the country and who later committed suicide, covered with bloody streaks.

Heller first met Lashai in Tehran, just before her imprisonment, when the dealer’s parents commissioned a massive landscape painting for their living room. After the revolution, Heller’s family lost that work, along with everything else, and she and Lashai fell out of touch. They reconnected years later, at Art Dubai. Heller included Lashai in a 2008 group show and secured her participation in the Chelsea Museum of Art’s “Iran Inside Out” exhibition in June 2009. (The work Lashai contributed, a three-part 2007 projected animation titled I don’t want to be a tree, I want to be its meaning, was based on Edouard Manet’s Luncheon on the Grass (1864–64) and the tale of Layla and Majnun, the Persian Romeo and Juliet.) The show’s opening coincided with Iran’s disputed national elections, in which reform candidates failed to win the presidency from Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in a vote widely suspected of being rigged, leading to demonstrations, the birth of the Iranian Green Party and a huge government crackdown — all events that brought Iranian art into the spotlight.

In April 2013, just weeks after her death, Lashai finally had her long-awaited New York solo debut, at Leila Heller Gallery in Chelsea and Edward Tyler Nahem Fine Art on the Upper East Side.

“She was going to do the show much earlier,” Heller says, “but she got sick, and she kept delaying it so she could do something really mesmerizing. All she wanted to do was to paint and create and produce. She was a very real artist on every level.”

Lashai’s video piece Keep Your Interior Empty of Food (Crows), 2010–12