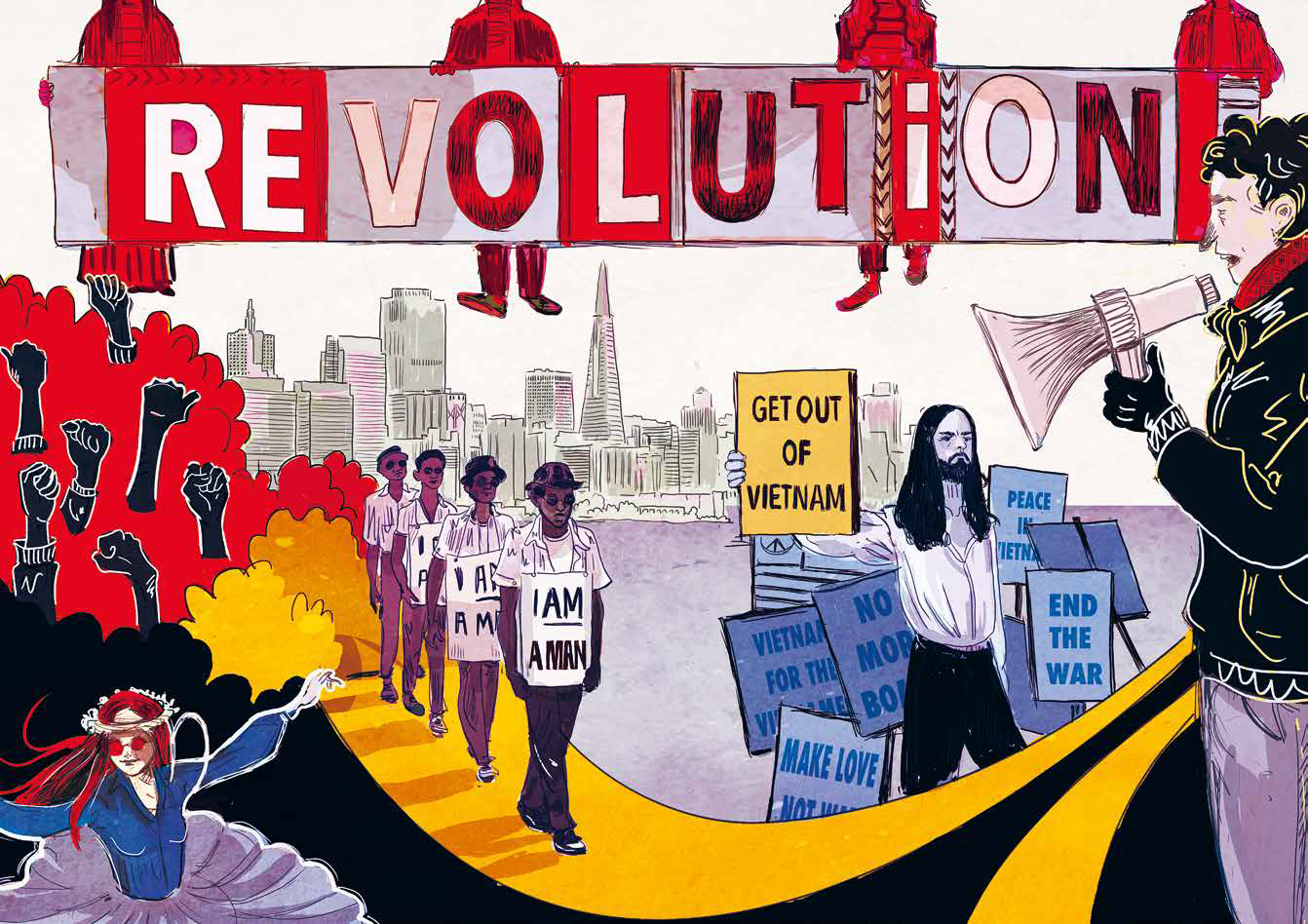

September 26, 2021In The Women Who Changed Art Forever (Laurence King Publishing), two Italian and, notably, female professionals — Valentina Grande, a writer, and Eva Rossetti, an illustrator and graphic designer — deploy the graphic novel to new ends. Rather than weave an illustrated tale of intergalactic or mutant supermen fighting dark lords, Grande and Rosetti portray very real super-heroines, retelling in each frame the recent history of feminism and reminding us of women artists who have defied the forces of patriarchal tyranny from the 1960s to the present.

The Women Who Changed Art Forever includes four vignettes presenting the imagined ruminations and factual careers of famous feminist creators: the radical 1980s art collective Guerrilla Girls; the very public icon Judy Chicago; Faith Ringgold, one of the earliest Black Lives activists; and Ana Mendieta, a Cuban émigré painter, sculpture and performance artist whose art star spouse, Carl Andre, was tried not once but twice for her 1985 death in a fall from their 34th-floor New York City apartment.

Loosely defined, graphic novels are stories, either fictive or true but usually complex, with lush illustrations, text and dialogue bubbles driving the narrative.

It’s not a new idea; the format existed long before the term was popularized in the 1980s. Medieval illuminated manuscripts, William Blake’s 1794 Europe a Prophecy and Richard Outcault’s 1897 collected comic-strip series The Yellow Kid are just a few of the precursors to today’s ultra-hip, critically acclaimed graphic novels, like Watchmen, The Dark Knight Returns and the brilliant, dark historical Maus.

Not incidental to the conception of The Women Who Changed Art Forever is the dominance of male creators in this genre and dude-dominated yarns. In a conversation with Introspective from her home in Rome, Rossetti echoes Grande’s statement in the foreword: Although the four heroines of the chapters that form the backbone of the book were carefully selected as exemplary, she notes, “thousands of women across the world are the protagonists. We wanted this to be an illustrated story of the culture-altering role of feminist artists in reshaping attitudes not just about gender but also about equity for all kinds of difference.”

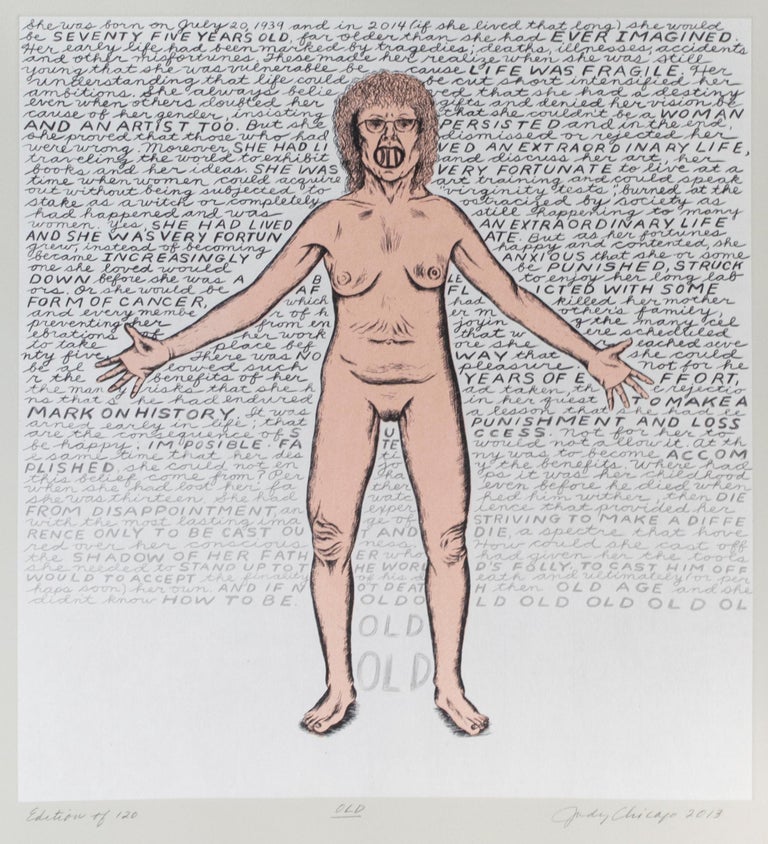

Illustrations move from skilled liming to fast comic-book caricatures. We watch an already famous Judy Chicago taking a 1985 walk and reminiscing about her youthful arc into feminism. We meet Chicago in 1971 as the frizzy-haired founder of the first feminist studies program at Fresno State, telling a gaggle of coeds she finds banter about boyfriends, hairdos and fashion boring and betraying a lack of curiosity.

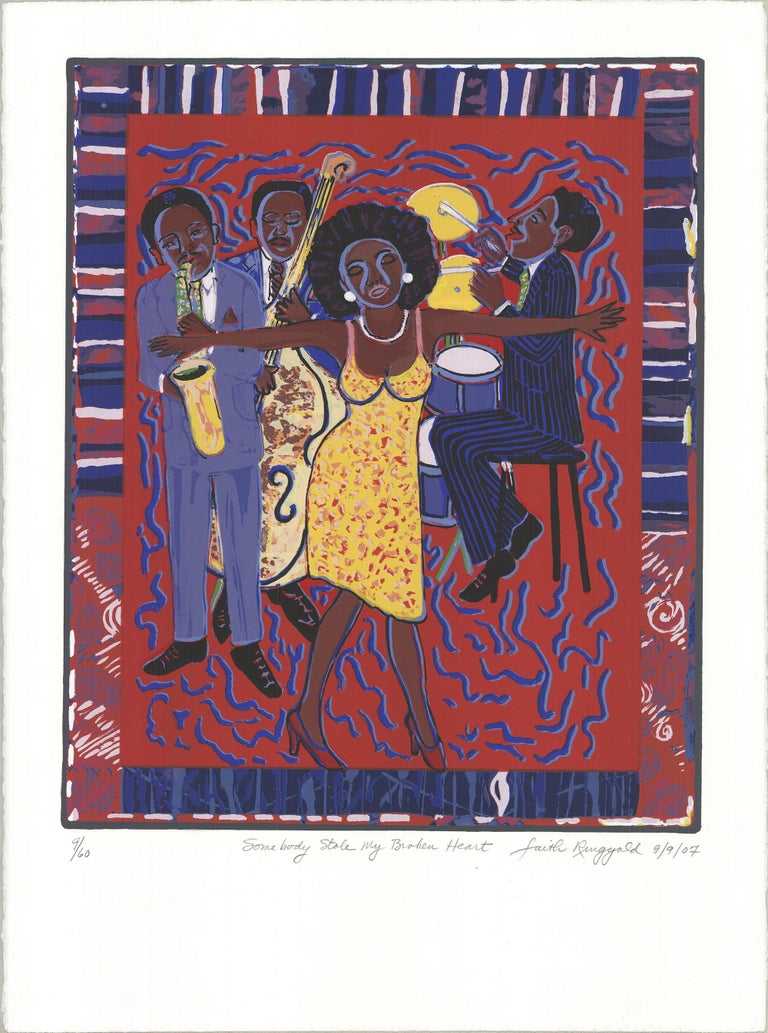

We see African American artist Faith Ringgold (now in her 90s) grow into self-awareness, founding the 1970 Women, Students and Artists for Black Art Liberation collective and recalling her epiphanic entry into Black and feminist activism. Ringgold is depicted in front of a generic museum (likely a reference to 1968 demonstrations outside the Whitney Museum of American Art protesting its overly white offerings), as the institution bigwigs finally agree to hear the Black male protestors.

The focus of Ana Mendieta’s chapter is not her tragic death. Rather, we see her as a child, airlifted out of Cuba as part of the Peter Pan project after Castro’s takeover, and later watch her artistic and political identity evolve as she reconnects with her body and explores its ties to the earth.

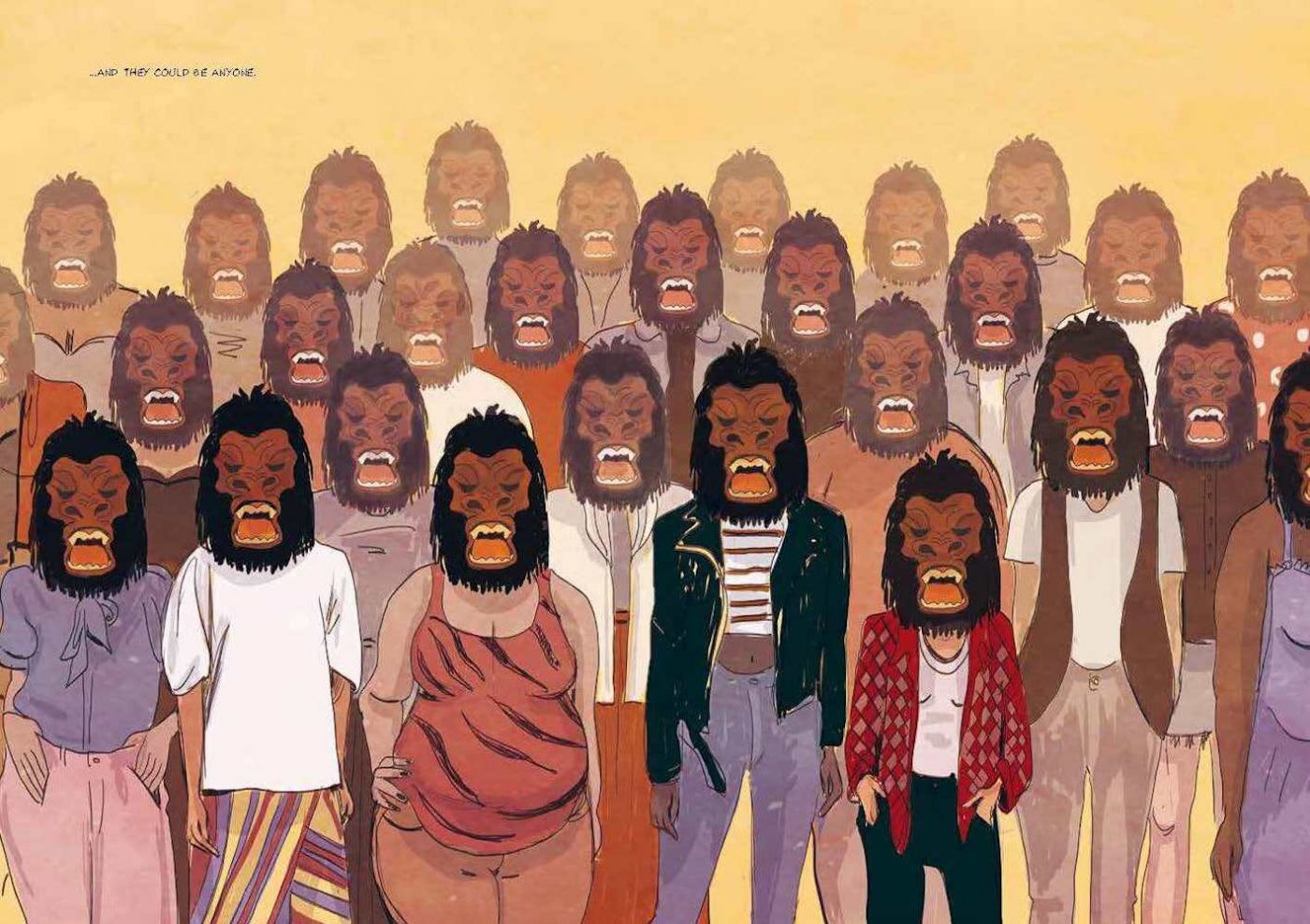

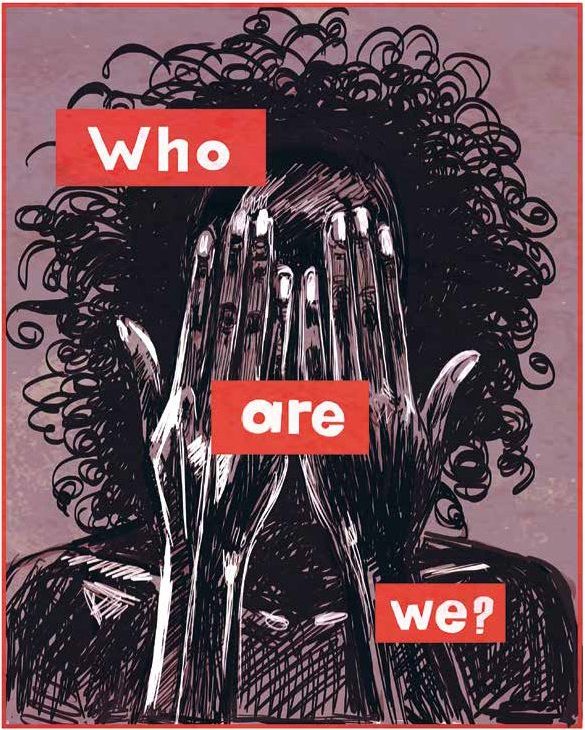

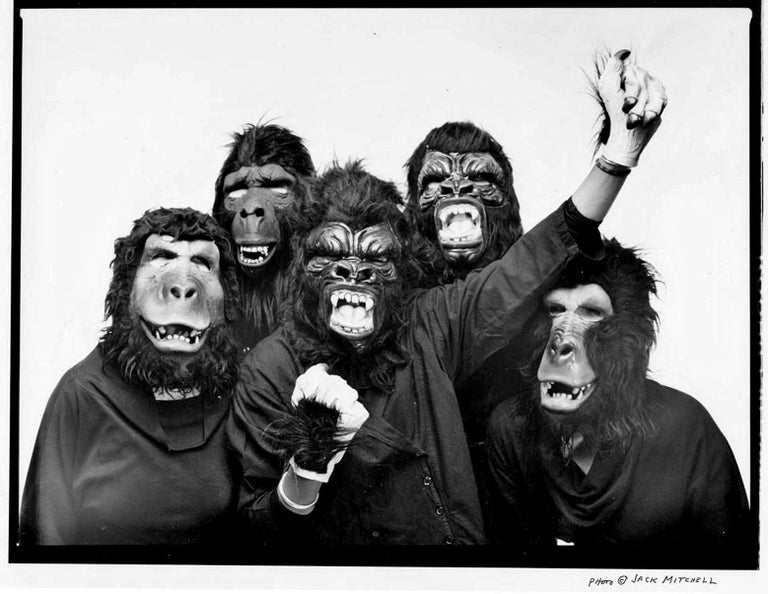

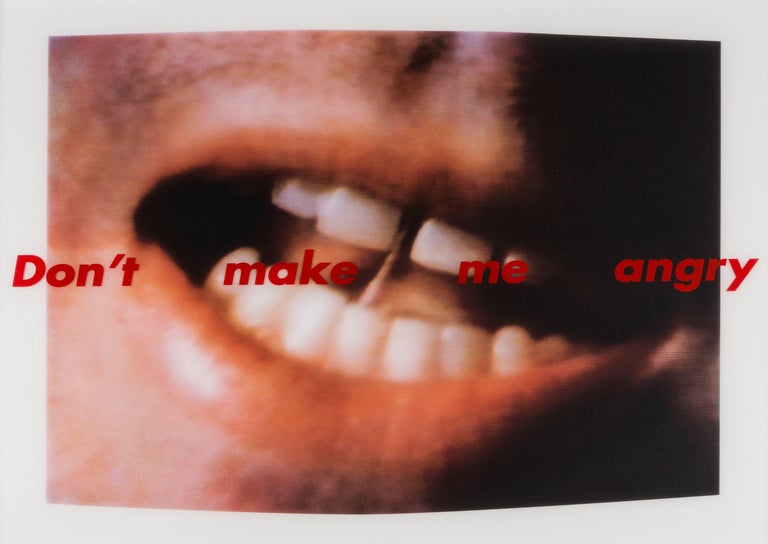

We learn that the Guerrilla Girls opted for anonymity in rebelling against art history’s singular male focus, and we see them don increasingly fierce primate masks while covering New York streets with artfully designed paste-up posters detailing museums’ and galleries’ biases against women.

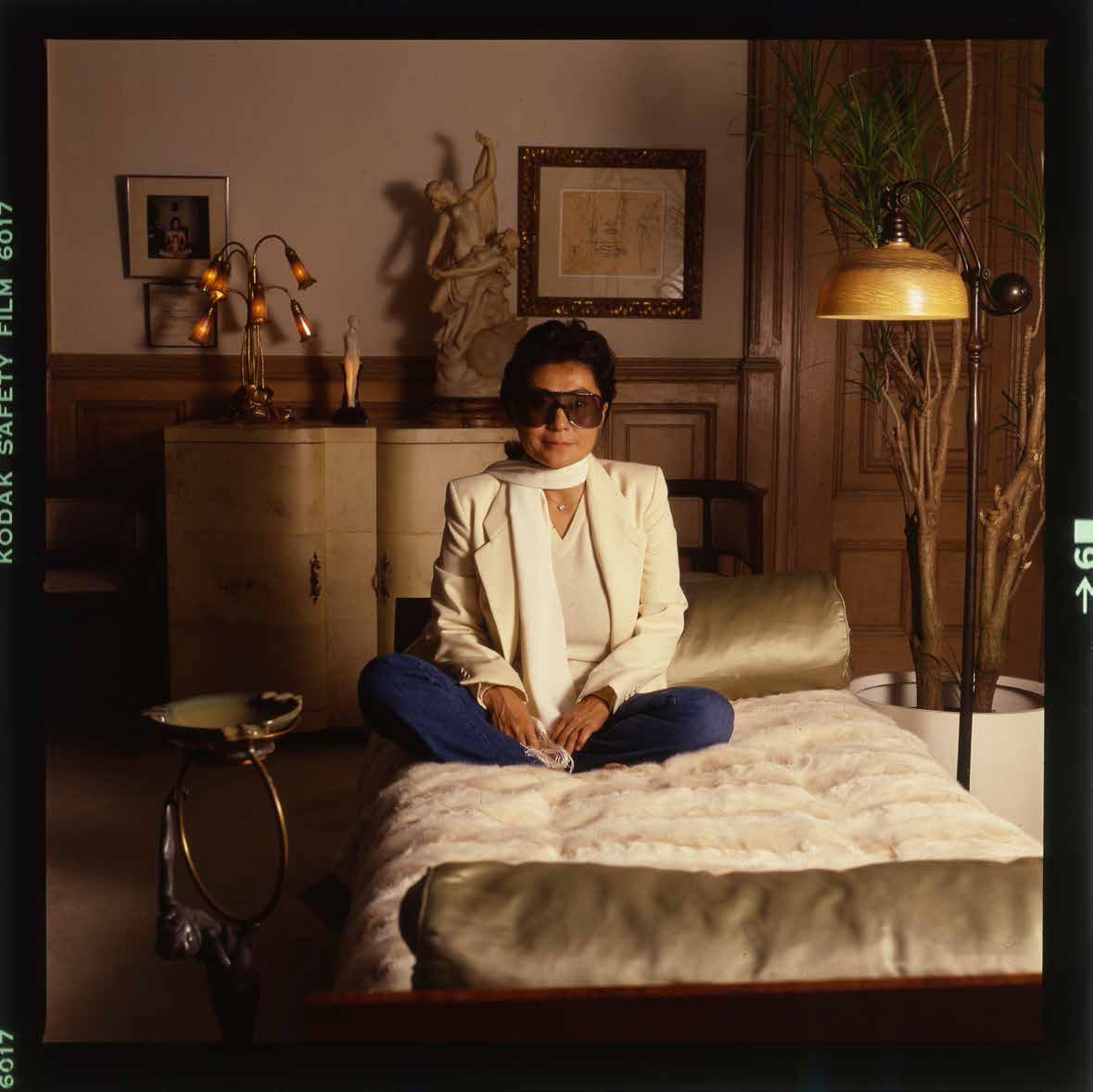

Drawings and text pay tribute to other movement notables, as well, including Yoko Ono, depicted in her 1964 performance work Cut Piece, and radical Black lesbian poet and theorist AUDRE LORDE.

You could, of course, read articles on the impact of feminist art and action, heavily footnoted and surgically parsing the issues in peer-reviewed journals, as this writer often does. But here is a graphic novel that relates its complex heroines’ tales accurately, charmingly and accessibly.