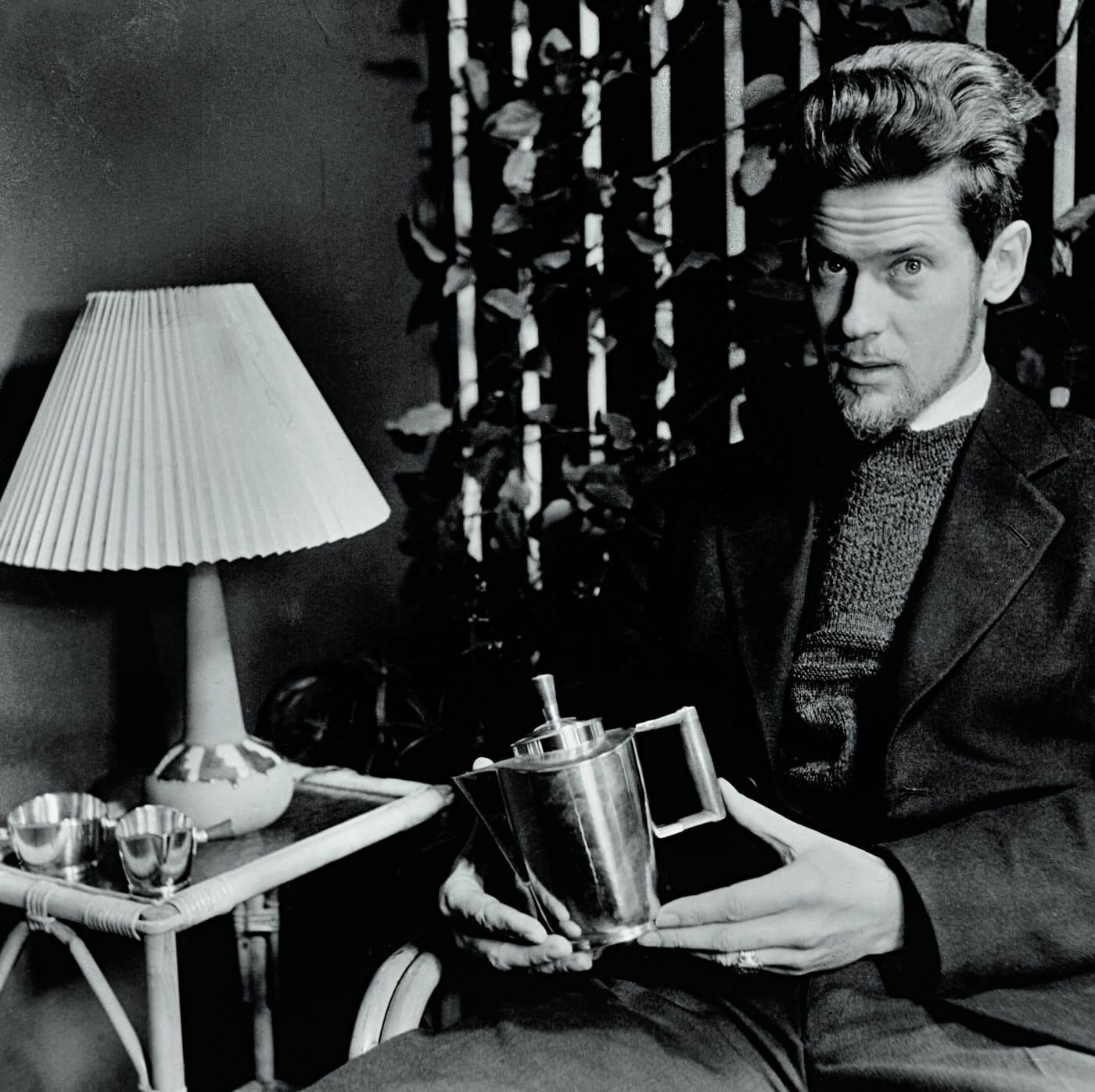

May 28, 2023Ironically, Dansk DEsigns, the tableware company practically synonymous with Danish design (“Dansk,” in fact, translates to “Danish”), was the brainchild of an American couple, Ted and Martha Nierenberg. The Nierenbergs, who founded the business in 1954, initially worked out of the garage of their Great Neck, Long Island, home and marketed their products largely in the United States. But they had a secret weapon: Jens Quistgaard.

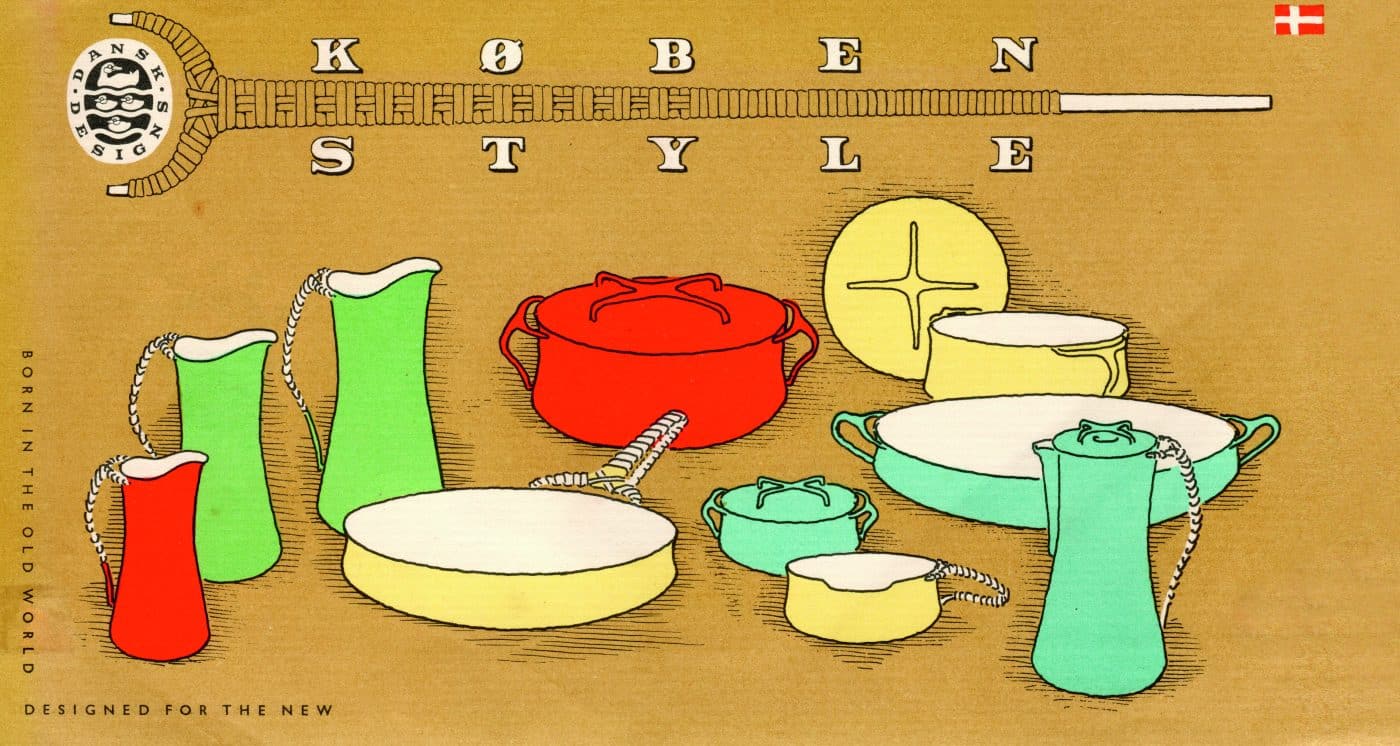

They’d discovered the Copenhagen designer on their honeymoon, which they’d spent traveling through Europe searching for top-quality goods that might form the basis of a business. After they hired Quistgaard and launched Dansk, their products swiftly came to epitomize the best of accessible Scandinavian design for mid-century American consumers, who fell for the firm’s staved-teak salad bowls, colorful casseroles and stainless-steel flatware, all of which managed to look handmade despite being mass-produced.

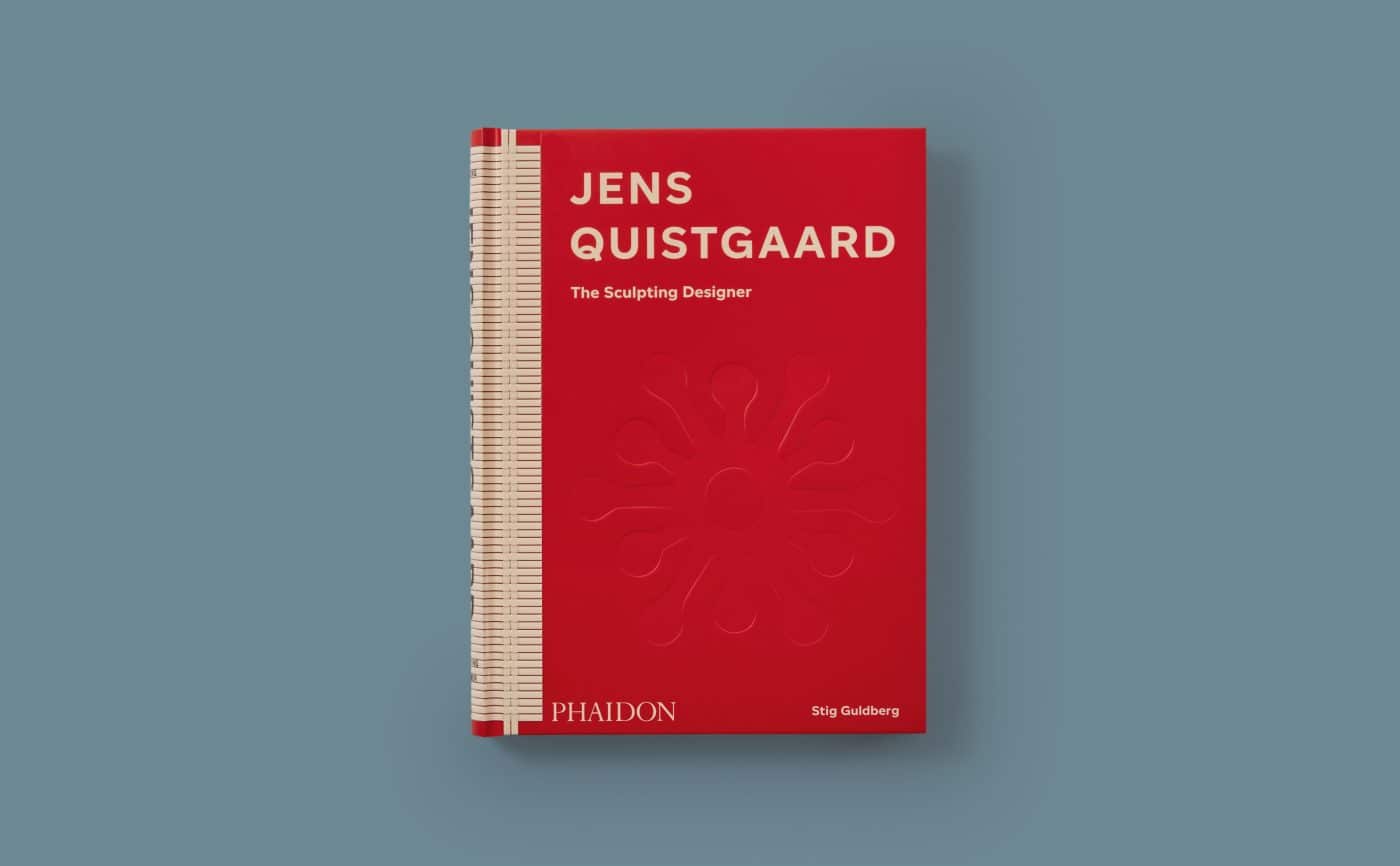

A new monograph, Jens Quistgaard: The Sculpting Designer (Phaidon), tells the story of the man whose innovations made Dansk products essential to so many American homes. Quistgaard, who was born in Copenhagen in 1919 and died in 2008, worked for the company for the better part of three decades.

Author Stig Guldberg came across Quistgaard’s work while trawling flea markets in the early 1990s. He eventually became a good friend of the designer’s and an authority on his work.

The book covers Quistgaard’s origins as a sculptor, portraitist and decorative artist and his transition to industrial design. It also includes an analysis of his most important pieces, like his steel Fjord flatware, and examines his many projects beyond his work for Dansk — including his silver Champagne flatware, in continuous production since 1947, and Ankerline enameled cast-iron casseroles — not to mention his forays into architecture, such as the small cottage he designed for himself on the remote Danish island of Vigø and the palatial, airy wood-and-glass home he created for the Nierenbergs in Armonk, New York.

Below, Guldberg shares with Introspective his recollections of Quistgaard — his personality, his creative approach and some of the reasons for his below-the-radar status in his native land.

Drinking glasses for Dansk, early 1970s

In the book, you describe happening upon one of Quistgaard’s Odin knives in a Copenhagen flea market in the early nineteen nineties and being fascinated by it. What was special about it?

First, I noticed the weight and that it was handmade of solid steel — unusual for flatware from that period. The form reminded me of the oars on Viking ships, and the blade was double-edged. I found all that very interesting and attractive.

You say you had barely heard of Quistgaard then. Why wasn’t he a household name in Denmark?

Many of his designs were very well known — for instance, his Kobenstyle cookware and his stoneware. But only a few knew the man behind the designs. First, he avoided publicity, especially journalists, in Denmark. He said he had had his share of fame in the U.S.

Second, he didn’t belong to the inner circle of Danish designers, who paid tribute to cool functionalism. He paid tribute to the sculptured form. He didn’t want to belong to a group. He always followed his own way.

Do you see his origins as an artist reflected in his products?

I think it can be seen in his sculpting approach and in his superb feel for materials. He always started by making a model by hand. He would say that’s because you’re not able to draw design — you have to see and feel it in three dimensions. Only then would he make drawings.

Meeting the Nierenbergs changed his life. What made the partnership work?

Ted Nierenberg took care of strategy and finance. He gave Quistgaard the support he needed for his creative work. For many years, it was a happy partnership. Later, disagreements arose between them — for instance, regarding whether more designers should be included in Dansk.

Quistgaard accused Nierenberg of being disloyal. Nierenberg answered that if he was seeking loyalty, he should go get himself a Labrador. People used to say that when they had these conflicts, they didn’t need a phone. The other party could be heard across the ocean.

You tell a fascinating story about Quistgaard’s first trip to New York, which prompted the designs for his Variation flatware and his first set of tableware, Fluted Flamestone.

Quistgaard found most of his inspiration in Denmark, primarily in simple tools for everyday use or in the ancient rural societies and the Vikings. He rarely mentioned how his trips to America directly inspired him.

The exception was his fascination with the New York skyline. The Variation flatware came to him when he and Nierenberg were walking along Fifth Avenue. And he said that when you were setting a table, it was very important to combine low pieces with high pieces. His inspiration for the high pieces were skyscrapers and the skyline.

What about the pepper mills, which are also wildly varied in height and style?

Quistgaard explained that working with them gave him an opportunity to let loose his imagination. He thought of them as small sculptures. But he also insisted that they are not sculptures, they are pepper mills. He said they remind you of something, but you’re not able to tell what it is.

Was he at peace with not being famous in Denmark? Or did he wish to be better known?

I think he enjoyed living on an island. I think he enjoyed the freedom and the silence and being away from publicity. Once, when I visited him there, a journalist from an important Danish newspaper had also come, to talk with him about a boat he’d made [a dinghy based on a Viking longship].

I helped his daughter get it into the water, and the journalist followed Quistgaard down to the boat, and they set off. When they came back, the journalist said that she was so surprised that Quistgaard was deaf, because he hadn’t answered one single question she had asked him.