October 16, 2022Talk admiringly these days about a “patriarch,” or even “tradition,” and chances are you will be met with a suspect look. These words, these notions have all but become anathema — and understandably so at this moment when all social givens are under interrogation.

But what if the patriarch in question was a bold and restless artistic innovator from a marginalized background who, in the late 19th century, altered the course of Western art through not only his revolutionary paintings but also his efforts to establish a forum for alternative artistic voices, including those of women?

That patriarch is none other than the groundbreaking Impressionist Camille Pissarro, who was born in the Danish West Indies to Jewish parents of Portuguese and French descent. Bridging tradition and revolt, he became a student of Corot and Courbet and, in his turn, generously mentored Cassatt, Cézanne, Gauguin and Van Gogh. It was “old father Pissarro,” as Matisse, another pupil, called him, who boldly organized the first independent painting exhibitions in late-19th-century Paris, so that he and his fellow renegades might have a forum for showing their then-shocking works.

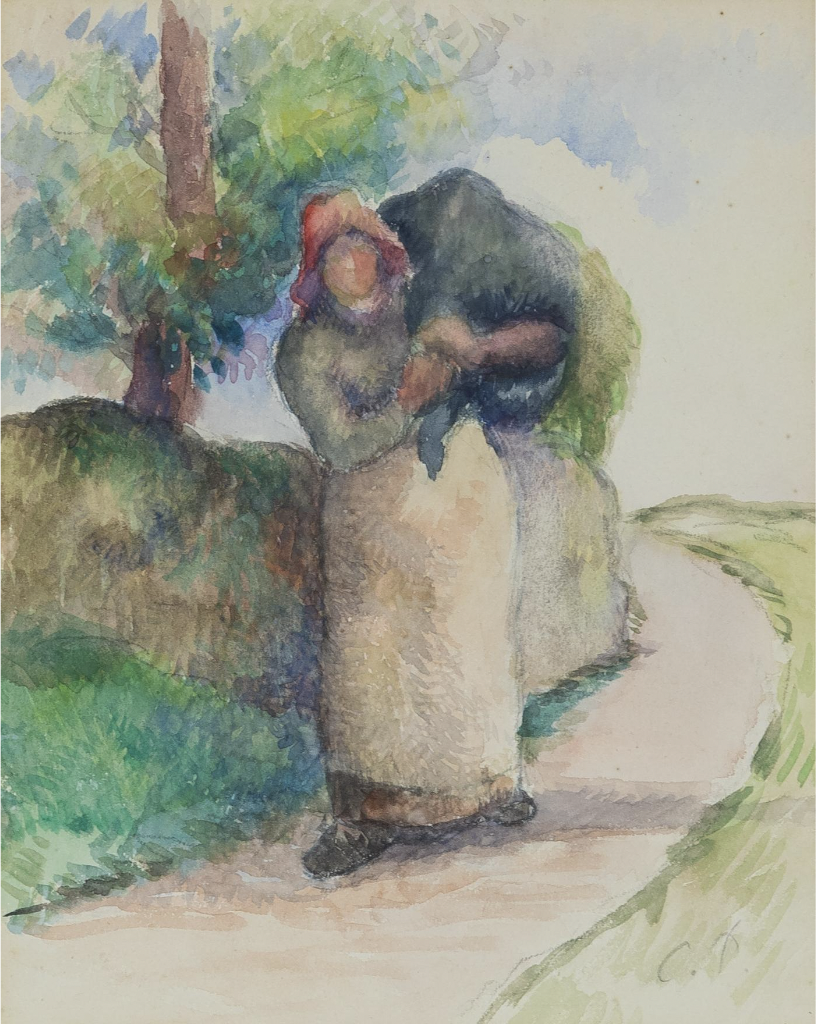

This was a patriarch who questioned institutions and embraced personal growth. Dissatisfied in his mid-50s with his ability to capture on canvas the ephemeral effects of light and color on a landscape, Pissarro schooled himself in the more “scientific” approach developed by two younger colleagues, Seurat and Signac. Eventually, finding their formulaic style stultifying, he returned to Impressionism, but with a new virtuosity.

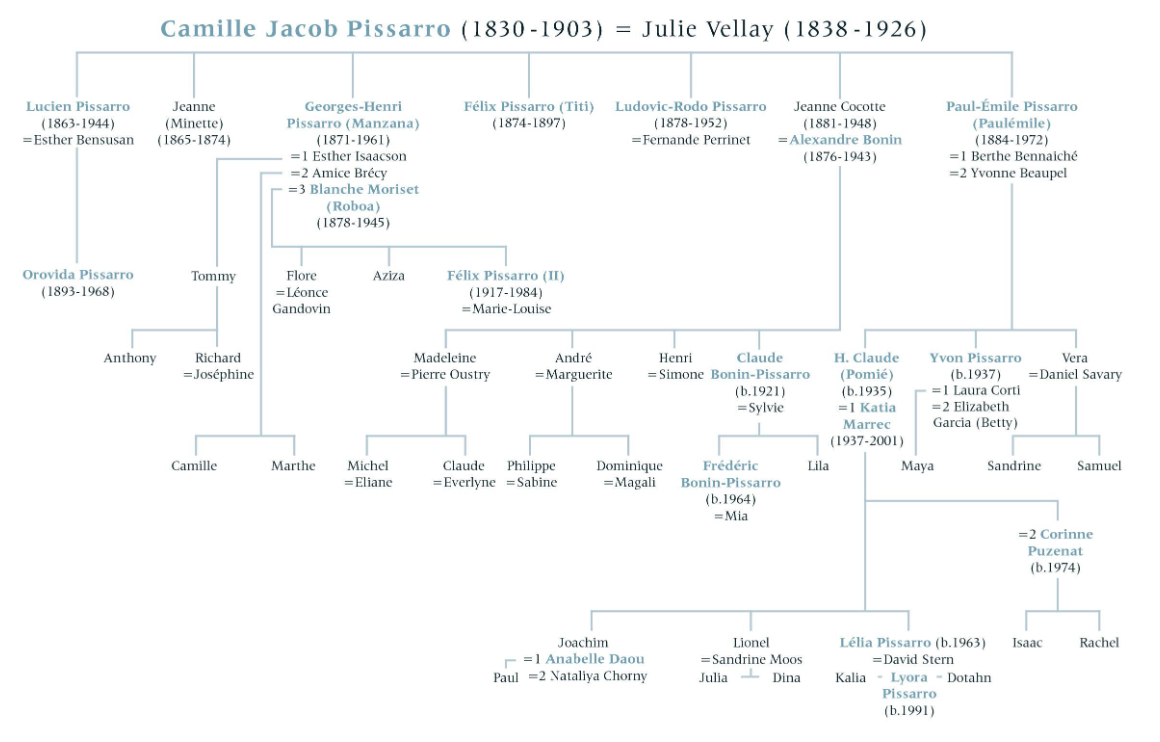

Even though he struggled financially for most of his career, Camille Pissarro’s enthusiasm for the magic of creation and the intellectual ferment of artistic camaraderie was so great that all five of his sons eventually became distinguished artists, much to the consternation of their long-suffering mother, Julie Vellay.

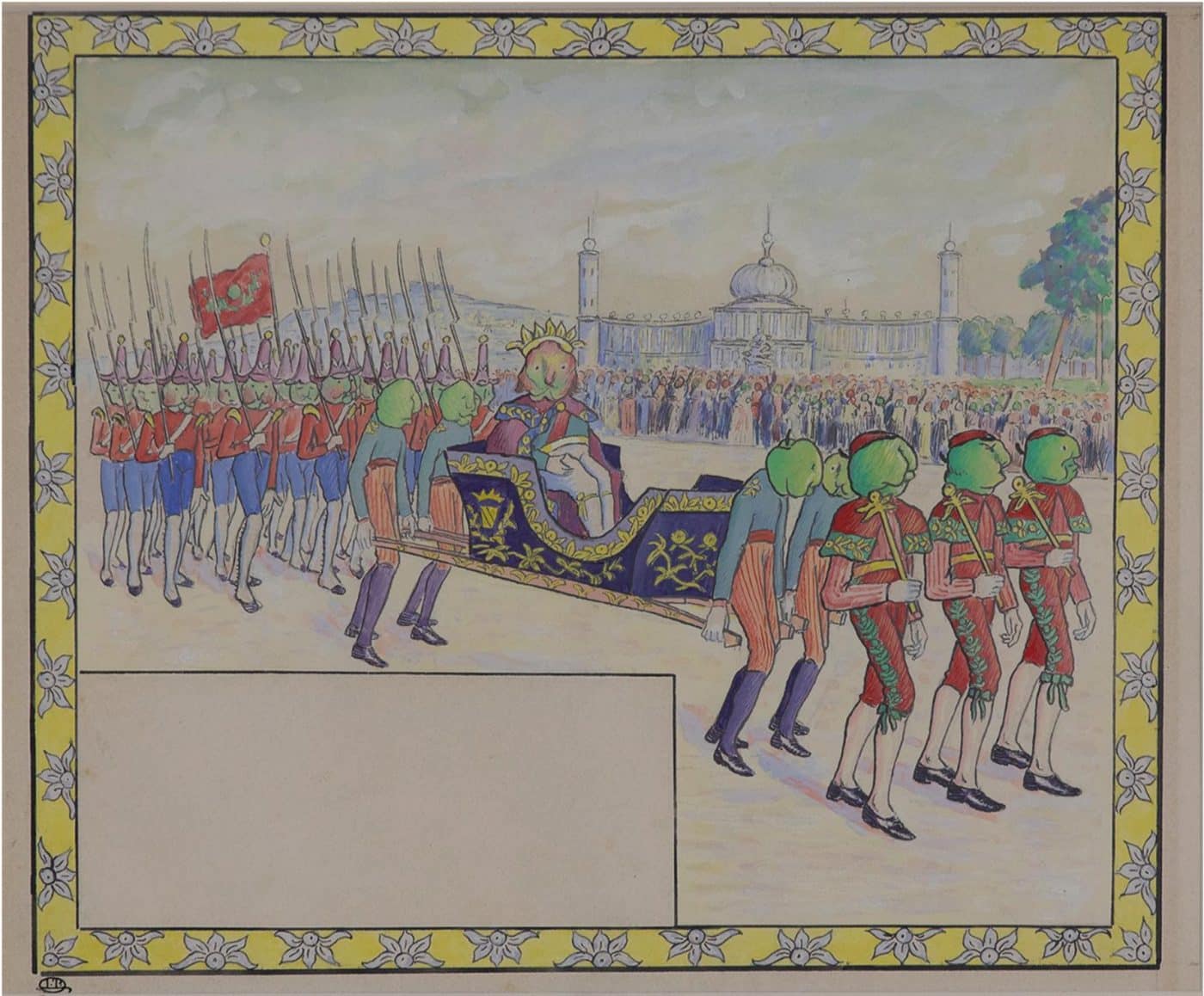

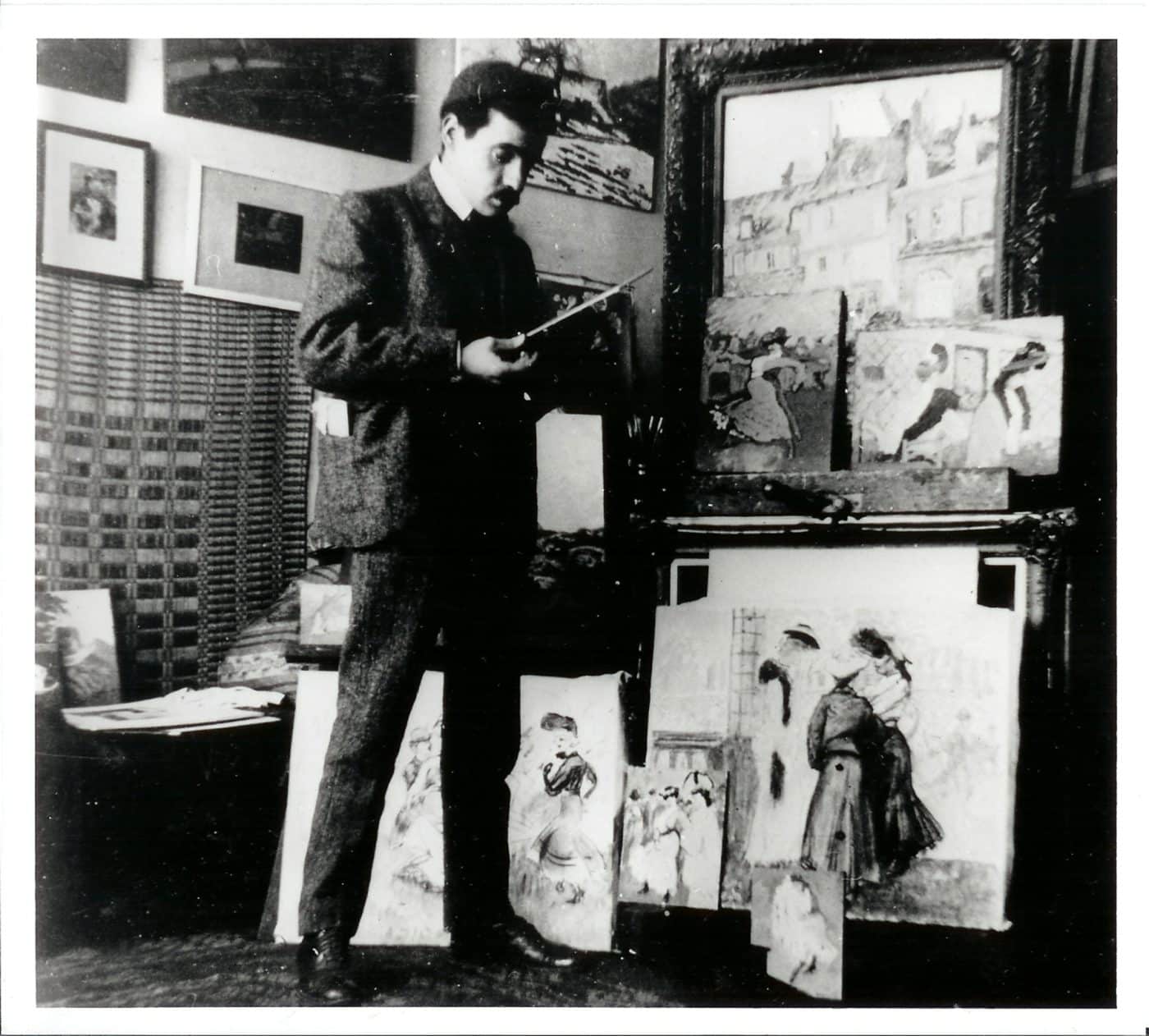

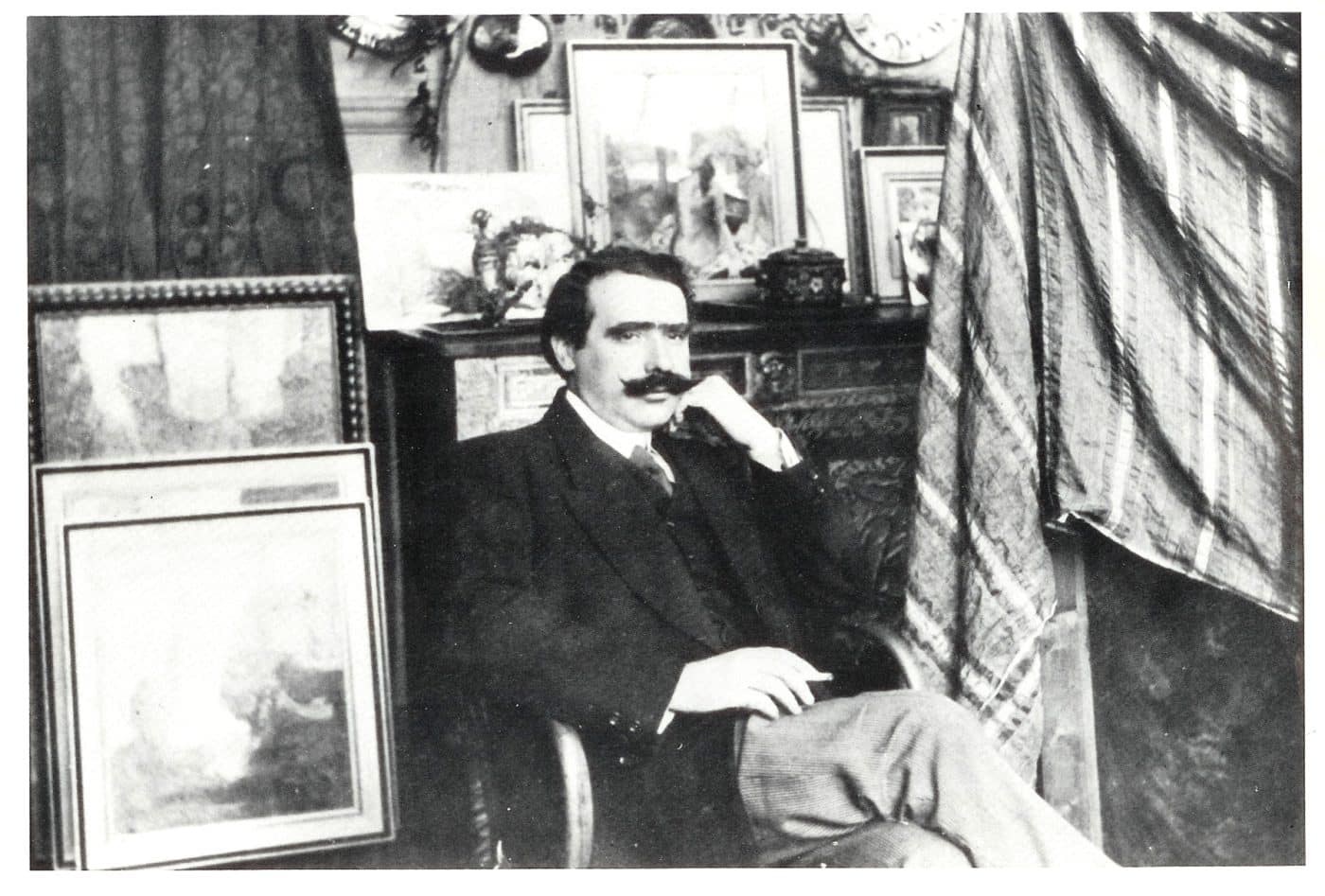

While all painted landscapes, the enterprising brothers took different paths. Lucien Pissarro, the eldest, settled in London and supported himself as a book illustrator and printer. Georges Manzana Pissarro, the second eldest, put his energies into the decorative arts, creating works with Orientalist themes.

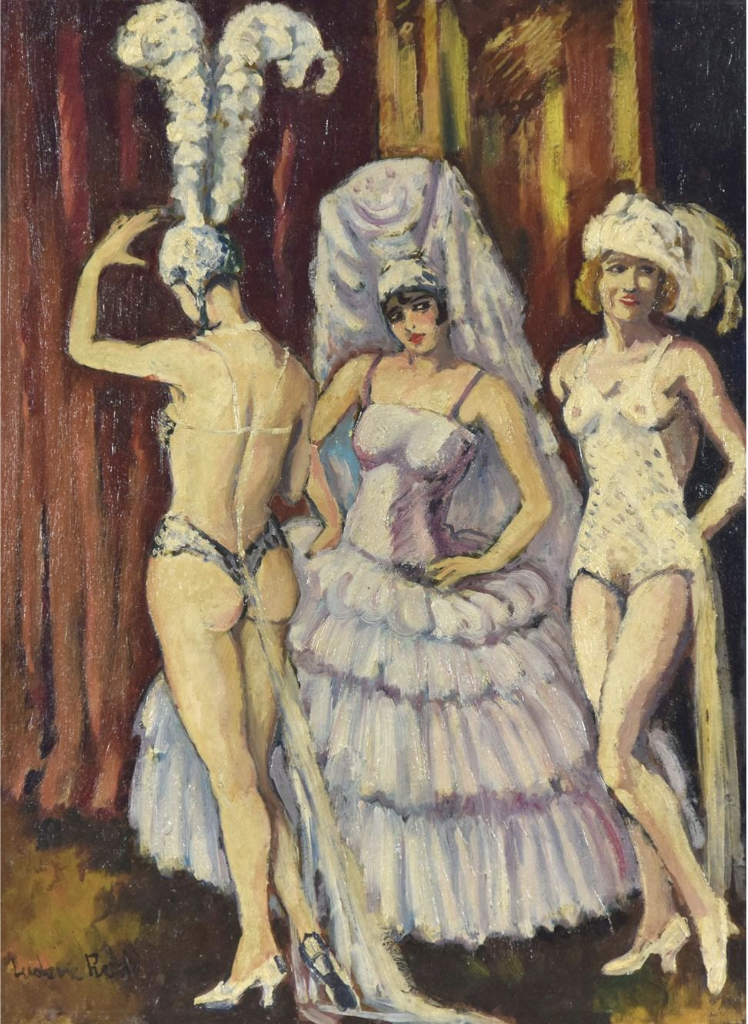

Félix, the third son, whom his father thought the most talented, was an expert draftsman and etcher with a special love of horses, as well as a a gifted caricaturist, but he died at 23 before he could make his mark. Ludovic-Rodo Pissarro, the fourth son, joined the Fauves and turned his artistic eye to Parisian nightlife.

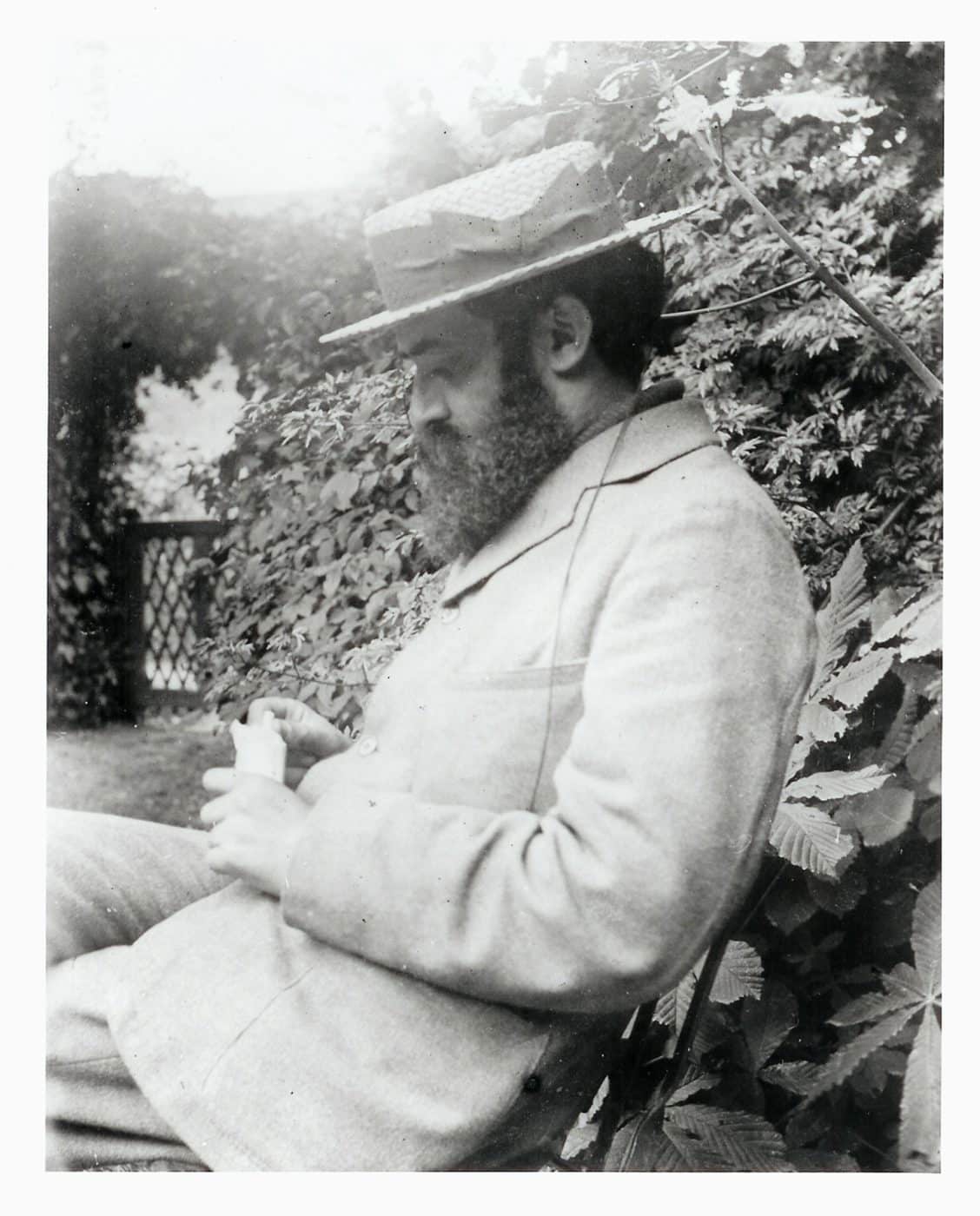

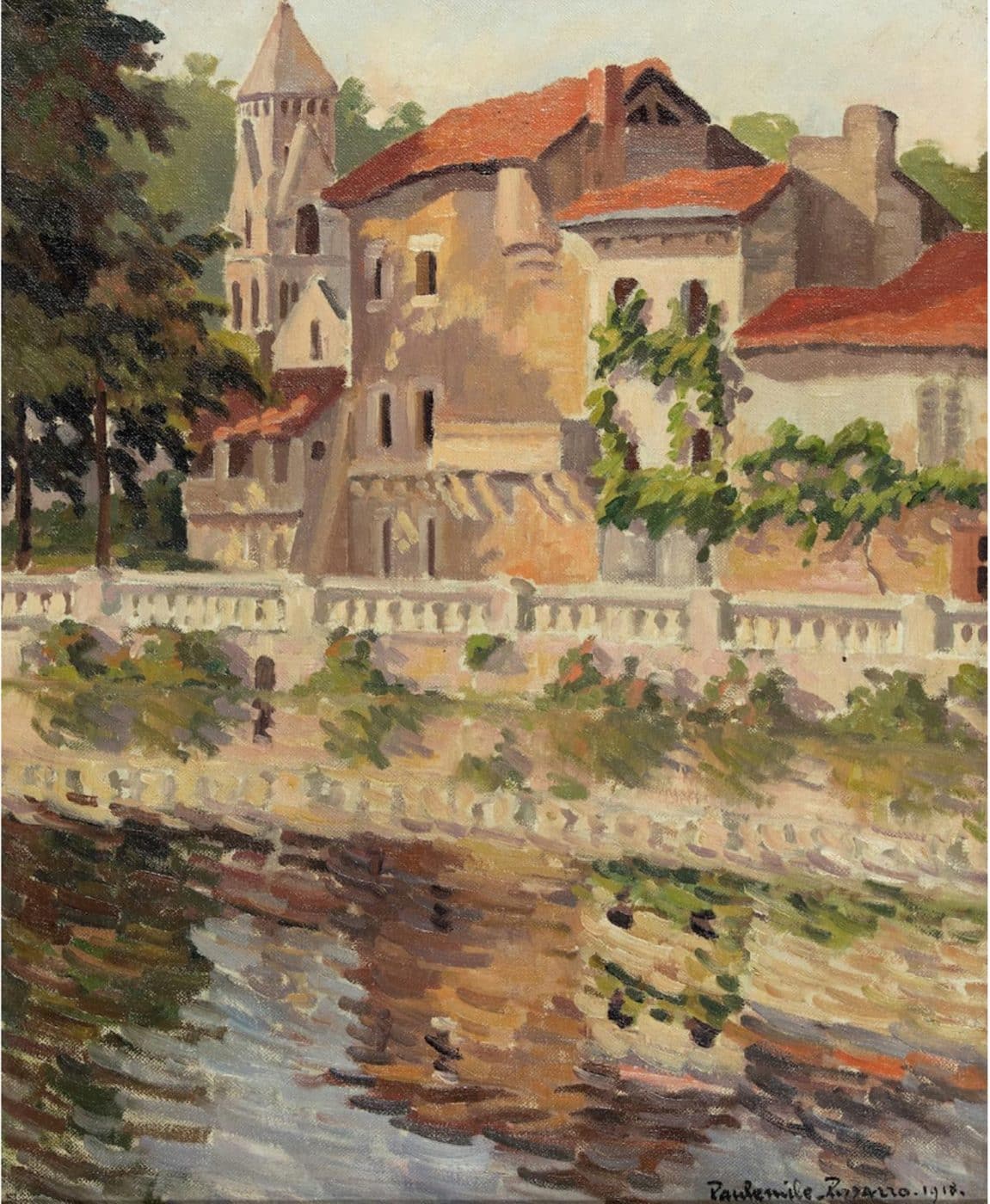

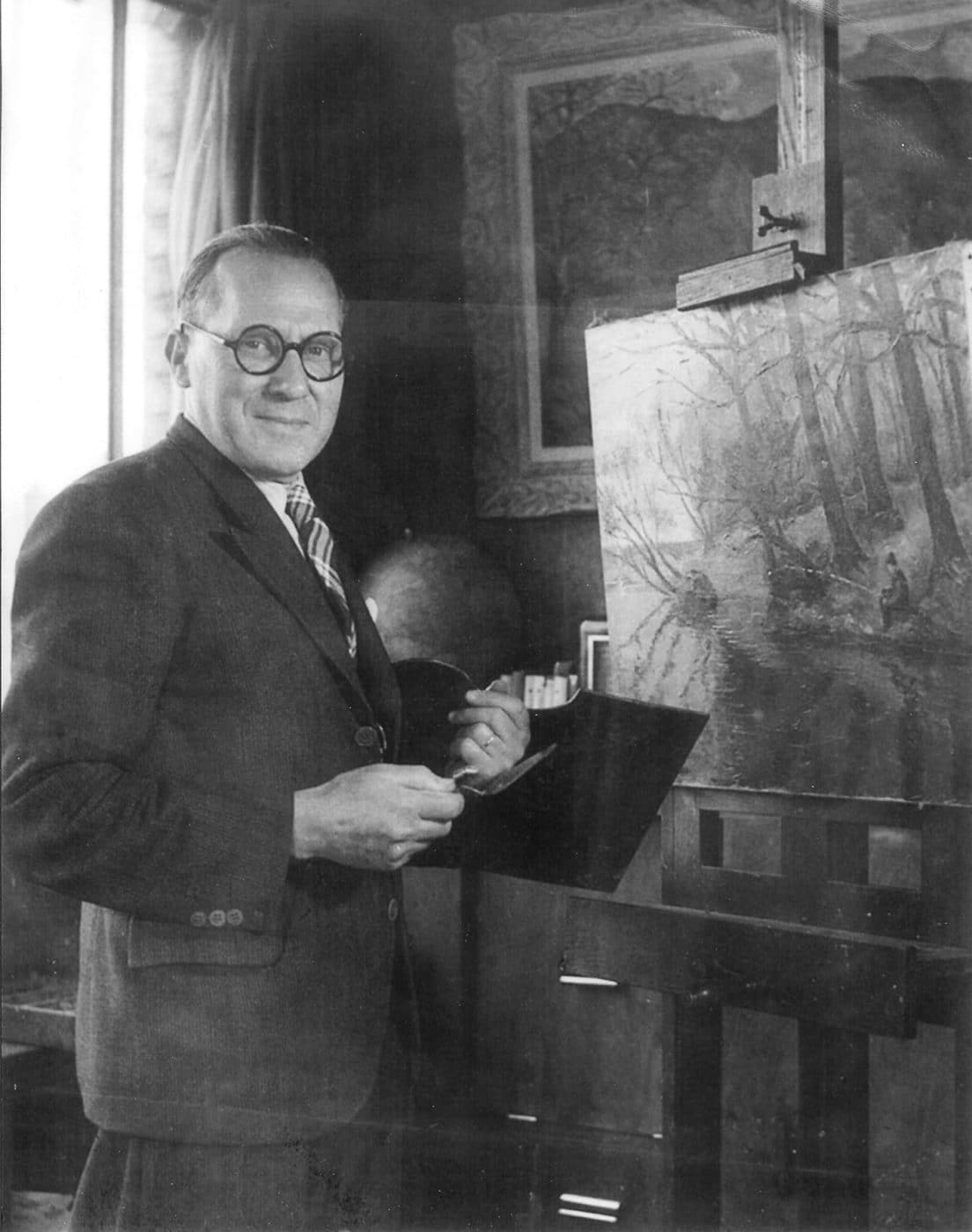

The youngest, Paul-émile Pissarro, only 19 when his father died, became the ward of Claude Monet. But bowing to his widowed mother’s wishes, he worked as an auto mechanic and test driver to earn a steady paycheck, and then as a lace and textile designer. Only after selling some watercolors in a show organized by Lucien did he dedicate himself full-time to painting, eventually gaining international renown.

If all that weren’t extraordinary enough, the offspring of these brothers, through four generations, have continued to influence the course of art history as artists, academics, curators and dealers. One of the most intriguing is Lélia Pissarro. Trained in the fundamentals of painting by her grandfather Paul-Émile, she is an adept Impressionist but has also developed her own abstract style.

Indeed, this dual commitment, to the traditions of her family and to her own original expression, has defined her life. She spends her days either making art or researching, authenticating and promoting the works of other Pissarros at the Stern Pissarro Gallery, in London, which she co-owns with her husband, David Stern. An art historian, Stern comes from a family of dealers specializing in 19th-century works.

With such backgrounds, it was all but inevitable that the couple, who married in 1988, would join forces in the art trade. Still, building their business wasn’t easy.

Lélia owned a trove of paintings by family members, but she says “there was not a question of selling them. While we were happy to show them to the public, those we wanted to keep in the family for future generations. So, we had to buy work. But we didn’t have the money to buy paintings, only works on paper.”

The pair’s first Pissarro family show, in a gallery in the picturesque town of Goring-on-Thames, featured some watercolors, etchings and crayon drawings belonging to Lélia and others specially acquired for the sale. They had so little extra cash that they couldn’t afford insurance for the art. “Every night, we would dismantle the exhibition, take all the artworks and put them in the hotel room, sleep, get up early, put all the artworks back in the car, and put the works back on the walls before the gallery opened,” Lélia recalls. Happily, the show sold out, and she and Stern were officially in the art business.

Today, in addition to representing various Pissarros in their posh duplex space in Mayfair, the couple show works by other Impressionists and members of the School of Paris, along with postwar abstractionists and contemporary artists.

In fact, they are as apt to put on a retrospective like the 2018 “Christo and Jean-Claude: A Life in Projects” as they are a survey like their most recent show, “Exploring Color in the Gallery Collection,” with works by artists ranging from the pioneering abstractionist Auguste Herbin to the Color Field master Paul Jenkins to the famed Op artist Yayoi Kusama. There are also, of course, more scholarly exhibitions, like last year’s “The Pissarros in England.”

The gradual expansion of the gallery’s focus has been a response to collecting trends. “We find today that there is a lot of cross-period collecting. There are people who collect Impressionists, modern and contemporary,” says Lélia. “And we have collectors who started in one area and evolved into another.”

Nevertheless, personal taste guides the gallery’s holdings. “David only buys works he feels passionate about. And we don’t always agree,” Lélia notes. “But he has a great eye for buying art . . . and will not put the stamp of our gallery on the back of a painting if it doesn’t represent the best possible work of an artist.”

Among the most recent artists to join the Stern Pissarro stable is the couple’s 31-year-old daughter, Lyora Pissarro, who, as tradition would have it, trained at her mother’s side. But rather than typical landscapes, Lyora paints deconstructed “mindscapes” on circular canvases (sometimes haloed in LEDs), which evoke both the mystical terrains of Agnes Pelton and the spellbinding geometries of Victor Vasarely.

Yet she is as much a vanguardist as her great-great-grandfather in her willingness to probe science and technology for fresh ways to capture inner visions that, as she puts it, “blend the imagined and the real.” She sketches her compositions on an iPad before painting, which allows her to also develop the color scheme. For her latest series, she teamed up with the digital-wizard Allaux Brothers, Alex and Oliver, to project imagery over her canvases, so that the scenes constantly morph, for an effect as meditative as contemplating a mandala.

Very much an artist of the 21st century, Lyora displays her latest works on Instagram and has created immersive experiences in the desert landscapes of the Amangiri Resort, in Canyon Point, Utah, and Cielos Crazy Diamond, in Cuyama, California. (In the latter venue, her sculptural piece was created in collaboration with artists David Cocciante and Fantin Guilloteau.) Her work can also be seen in the solo show “Mindscapes,” opening October 20 at the Tuleste Factory gallery in New York’s Chelsea neighborhood.

Is Lélia proud of her daughter? “Not at all,” she replies. “ ‘Proud,’ for me, means taking some of her success on my shoulders. Instead, I am humbled, speechless with admiration. She has managed to achieve something completely different, completely new.”

And what could be more in keeping with the precedent set by Camille Pissarro? Except that now, the tradition is in the matrilineal line.