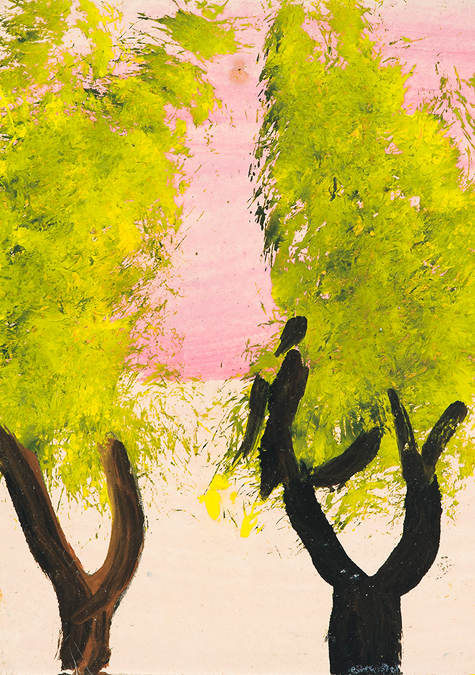

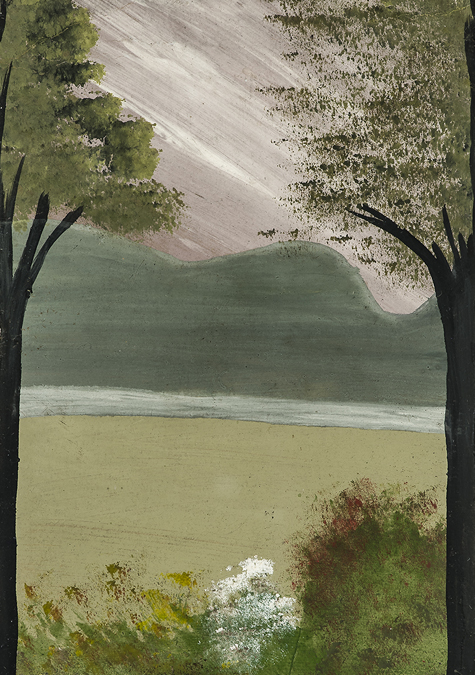

The late Antiguan painter Frank Walter, who lived his last 25 years as a recluse, is the subject of the moving exhibition “Lonely Bird” at New York’s Hirschl & Adler Gallery. Portrait © Sean Donnola; Above: A detail of Landscape with Fence and Red Sky. Unless otherwise noted, all photos by Eric W. Baumgartner, courtesy of Hirschl & Adler Modern, NY, © Estate of Frank Walter

January 25, 2016©

Frank Walter always knew he was special — the trouble was no one believed him. For much of his life, the self-styled Seventh Prince of the West Indies lived as a recluse in a dilapidated hut high above Antigua’s remote Ding-a-Ding Nook. No matter that the self-taught artist enjoyed a privileged upbringing and possessed a keen intellect that led him to manage a sugar plantation at age 22, becoming the youngest Antiguan of color to do so. Walter chose to live for the last 25 years of his life in that rudimentary structure without running water or electricity. And his paintings — raw miniature landscapes of his beloved island and Scotland, as well as portraits both real and imagined, including one of Charles and Diana as Adam and Eve — would remain mostly unseen until after his death, at 83, in 2009.

New York– and Maryland-based art historian and landscape architectural designer Barbara Paca had long been traveling to Antigua, both for work and pleasure, and was intrigued by tales she heard from Sir Selvyn Walter, the island’s former Minister of Economic Development and Tourism, of his “genius” cousin who lived alone on a hill. In 2004, Paca was escorted up to Frank Walter’s hut by members of his family and it was “love at first sight,” according to Paca. “Frank told me about his ardor for the Grampian ‘hills’ of Scotland and taught me many valuable lessons about botany and the craft of an Antiguan planter,” much of which she says she has applied to her work on projects there, including the current sustainable and historically appropriate landscape design for the grounds of Government House, the Governor-General’s official residence.

Following Walter’s death, Paca spent years working with his family to document his complex life story and organize the reams of writings — nearly 25,000 typed pages of autobiography, history and philosophy — as well as numerous paintings, carvings, photographs and handmade frames that filled his ruggedly austere home. It was that hut, ironically, that brought Walter to the attention of fairgoers at Art Basel Miami Beach in 2013. Scotland’s Ingleby Gallery (who had previously shown Walter’s paintings alongside those of Alfred Wallis and Forrest Bess) recreated it to dramatic effect with some of Walter’s actual possessions, including a bed made out of a door and many of the artifacts he’d collected or created himself. The ABMB exhibit was a hit with critics and collectors alike, and the artist’s heirs felt it was time to bring a carefully selected group of his works to New York. Hence “Frank Walter: Lonely Bird,” the sensitive and thoughtful exhibition on view at Hirschl & Adler Gallery now through February 13.

Curated by the gallery’s associate director Tom Parker, “Lonely Bird” skillfully brings visitors into Walter’s singular world. Atop a desk fashioned out of old cardboard boxes sits a battered typewriter, a strip of paper sticking out from behind the platen. “It was clear to all who had come to know me that I had become quite an invincible character,” Walter’s text reads. “Some attributed my strange powers as they had put it to darkness, others who were better informed had recognized the hand of God moving mysteriously to protect me and assist me in all my endeavors.” Here is the mind of Walter at work — fertile, visionary and deeply flawed by delusions of grandeur.

Walter’s astounding body of work reveals an epic commitment to creative output. He referred to himself as “Lord of Follies” and obsessed over his genealogy in text and home recordings. Of mixed heritage, he believed he was descended from some of the noble houses of Europe, ranging from Charles II to Franz Joseph of Austria. Walter moved to England in 1954, partly to research his imagined aristocratic roots, and toured Scotland in 1960. Disillusioned by the racism and lack of opportunity he found there, he returned to Antigua, but not to his career on the plantation. Instead he immersed himself in his art.

“Walter was well acquainted with ancient Arawak and Carib art, particularly from his years on the neighboring island of Dominica, where he spent time with the modern-day Carib people,” explains Parker. “The simplified, flattened forms and patterning no doubt informed Walter’s distinctive sense of abstraction. And the exaggerated human features and spiritual underpinnings of Arawak carvings found direct expression in Walter’s own haunting sculpture.” These influences can be seen in such beguiling images as a rose-pink sunset, painted on the blank side of a Polaroid film package and framed using the empty cartridge, and an unassuming house, reminiscent of the cookie-cutter structures found in California’s suburbs, simply titled Dream House. Walter yearned to be understood and for the world to see Antigua as he did: an island where lilac harbors were as still as the night sky, where fiery suns lit vast fields, and black men carried their heads as high as kings.

It’s fitting, therefore, that Walter’s work is going to be included in the next Venice Biennale as the anchor of the first-ever pavilion for Antigua and Barbuda. “Frank’s work as a planter, philosopher, writer and person who used artistic gifts as a form of therapy promises to be compellingly explored in Venice,” Paca says.

Even as outsider art gains critical attention, Walter’s work shows us that there’s still much to be discovered on the margins of the mainstream market. He may not have found success in his lifetime, but his striking images bring us that much closer to knowing Antigua — and the lonely recluse who called it his home.