March 27, 2017A new show at Chicago’s Driehaus Museum — which is housed in the impressive Gilded Age mansion above — celebrates French posters from the decades around the turn of the 20th century. Top: Folies-Bergère, La Loïe Fuller, 1893, by Jules Chéret. All images © Driehaus Museum, 2015, unless otherwise noted

When the view is right and the light is kind, Paris is a city in which time seems to stand still. So seductive are its historical charms that it is easy to forget that the French capital was once a matrix of modernity. From the hovel-leveling avenues of Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann to the sky-piercing tip of the Eiffel Tower to the daring depictions of the everyday created by Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Edgar Degas, Paris in the 19th century epitomized the new.

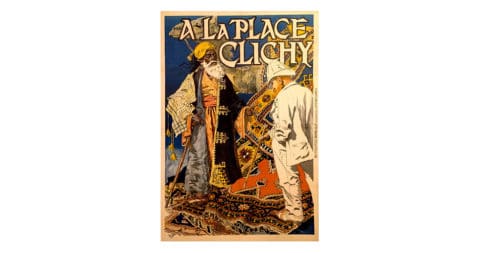

The city street — the artery of commerce and the venue of the promenade — was central to this ever-accelerating sense of contemporary life. And posters were key to the fabric of the cosmopolitan thoroughfare. Whether advertising the latest tobacco product or a must-see cabaret star, the poster communicated the richness of the urban experience. Chicago’s Driehaus Museum — housed in a Gilded Age mansion steps from Michigan Avenue — is currently celebrating the art and artists of those days with “L’Affichomania: The Passion for French Posters,” on view through January 7, 2018.

The exhibition draws from the collection of the museum’s philanthropic founder, Richard H. Driehaus, which focuses on European and American fine and decorative art from the decades around the turn of the 20th century. Organized by independent curator Jeannine Falino, the show comprises significant work by Jules Chéret, Eugène Grasset, Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Alphonse Mucha (the last is also the subject of a comprehensive new study published by Skira). In an interview with Introspective, Falino shared some insights into what’s on display at the Driehaus.

Posters — especially in our digital age — don’t seem all that remarkable. But in the Paris of the 1880s and ’90s, they were a phenomenon.

Yes. Before this, posters were black and white, densely lettered and didn’t read very well. Then, suddenly, with Jules Chéret, there were big, bright, colorful drawings, and the words were beautifully set to complement the image, which was first and foremost. This marked a major shift, the beginning of the first truly visual advertising: a big exciting image, a couple of bold words, and you immediately absorb the subject matter.

Chéret’s Théâtrophone, 1890

Posters are quite often dismissed as ephemera, but even as these works were being produced, they were esteemed as collectible.

People responded immediately to the excitement of these images — and, of course, they were free for the taking, as they were on the street. But also, printers actually set some aside and sold them to collectors or dealers. Edmond Sagot became the first to sell posters in a gallery, in 1886, and the Salon des Cent [a commercial exhibition begun in 1894] was all about posters.

Did the public ever rebel, as we sometimes do today, against the blight of incessant advertising?

With so many posters appearing, the city created specific areas where they could be displayed, long walls called hoardings and, of course, kiosks. But there were people who got tired of them. One journalist wrote, “Nothing dates so insolently from today as the illustrated poster, with its combative color, its mad drawing,” complaining that everywhere, posters announced “an oil, a bouillon, a fuel, a polish or a new chocolate.”

And there’s a wonderful, kind of hyperbolic story by Émile Zola [“Une victime de la réclame”], about a guy who goes out and decides to act on every poster he sees and essentially kills himself in the process. So people understood very early on that they did have a downside. But some people felt that for those who didn’t have much, seeing these beautiful images, these lighthearted forms, might alleviate the grimness of their day-to-day lives.

Grasset’s Cycles & Automobiles, Marque Georges Richard (Cycles & Automobiles), 1899

Motocycles Comiot, 1899, by Théophile-Alexandre Steinlen.

The show includes Toulouse-Lautrec’s iconic images of dancer Jane Avril and La Goulue of the Moulin Rouge.

Yes, and there’s a really very wonderful one by Chéret of Loïe Fuller, the American dancer who went to Paris and performed in long, flowing gowns lit with colored lights. The poster shows her twirling, her arms out, her red hair flying to one side. It looks like the whole poster is spinning, and I think it’s very successful in conveying the excitement of the dance.

Posters were used to sell everything under the sun. What is one of your favorite product-driven examples?

I love Steinlen’s Motocycles Comiot [1899], which shows a woman on a bicycle. She represents what was known at the time as “the new woman.” In the late 19th century, women really couldn’t leave the house without being in the company of their husbands. It wasn’t seemly. But bit by bit, women broke out of the house, propelling themselves under their own power.

I love how this poster shows a woman pedaling away, startling the geese in the road and probably everyone else as she sails along. And I love the two peasants in the background. They remind me of the field workers in Jean-François Millet’s L’Angélus [1857–59], who stop to pray as they hear the bells tolling. In the poster, the couple is bent over in mid-labor — and there she goes!

Some Covetable French Posters on 1stdibs