February 2, 2020A Greek red jasper scaraboid depicting Perseus, Classical Period, 4th century B.C. Top: A Roman carnelian ring stone bearing a portrait of Octavian, mid-1st century B.C. (left), and the “Marlborough Antinous,” a Roman black chalcedony intaglio portrait of Antinous, A.D. 130–38. Images courtesy of the Getty Museum

Ancient engraved gems are among the most visually compelling cultural artifacts, because of their minute size, the precision of their execution, their aesthetic allure and the fascinating, typically elite patrons for whom they were made.

Seventeen extremely rare and precious examples of this art were recently acquired by the Getty Museum, in Malibu. The cache — comprising rings, single gems, a signature cylinder, scarabs and other works — are of Minoan and archaic and classical Greek origin, as well as from Etruria and Rome. As an indication of the trove’s caliber, the museum paid well over a million dollars for a single object.

Gems like these — intimate and revealing — are not simply ancient status symbols or fab antique bling. They are tiny Rosetta stones, providing a way to “read” the past, speaking to us about trade between civilizations, about a culture’s myths and archetypes and about an era’s influencers, values and power struggles. Not least, they provide insight into the technological advances of their day.

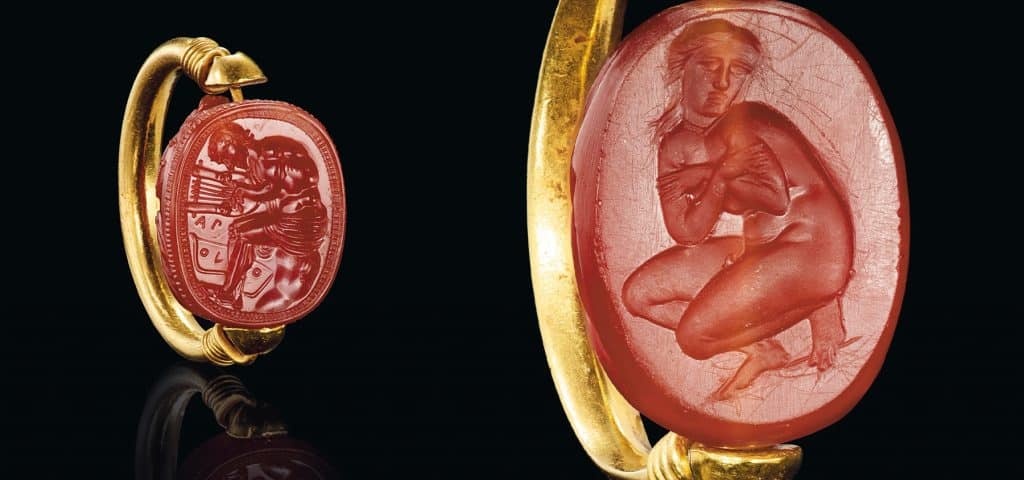

Left: Etruscan gold finger ring holding a carnelian scarab carved with a figure of Aplu/Apollo, 4th century B.C. Right: Greek gold swivel ring with a carnelian scarab depicting Aphrodite, Classical Period, 4th century B.C.

Many of the Getty acquisitions have never been seen outside their previous aristocratic owners’ private circles; they were only recently illustrated for the first time in Masterpieces in Miniature: Engraved Gems from Prehistory to the Present (Philip Wilson Publishers) by Claudia Wagner and Sir John Boardman.

Etruscan carnelian scarab depicting the rape of Cassandra, mid-5th century B.C.

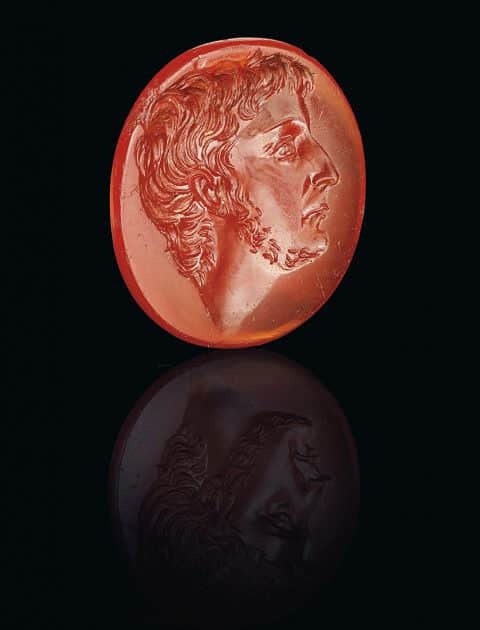

Among the gems are showstoppers you won’t want to miss seeing in person, or IRL as we say, because photographs simply cannot do them justice. There is an exquisite portrait of the Roman emperor Hadrian’s young lover, Antinous, detailed to the last sensuous strands of hair. A beautiful carnelian ring-stone portrait of Julius Caesar’s nephew and adopted heir, Octavian, exemplifies the insights these personal gems can offer into both aesthetics and history: Octavian’s portrait here, austere and life-like, with aquiline Roman features, contrasts with his idealized and Hellenized depictions after he became Emperor Augustus.

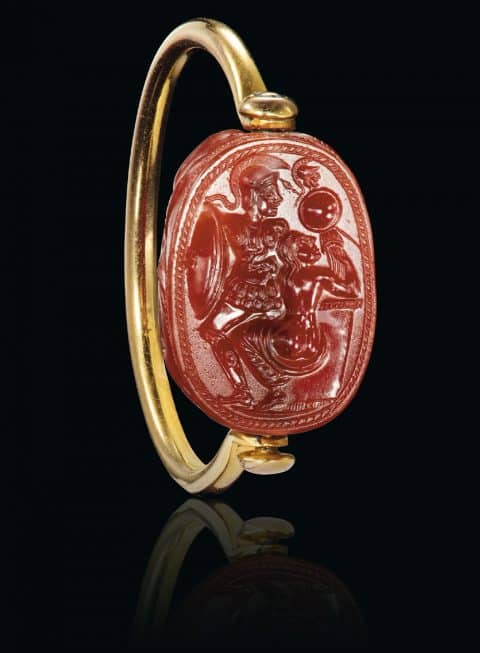

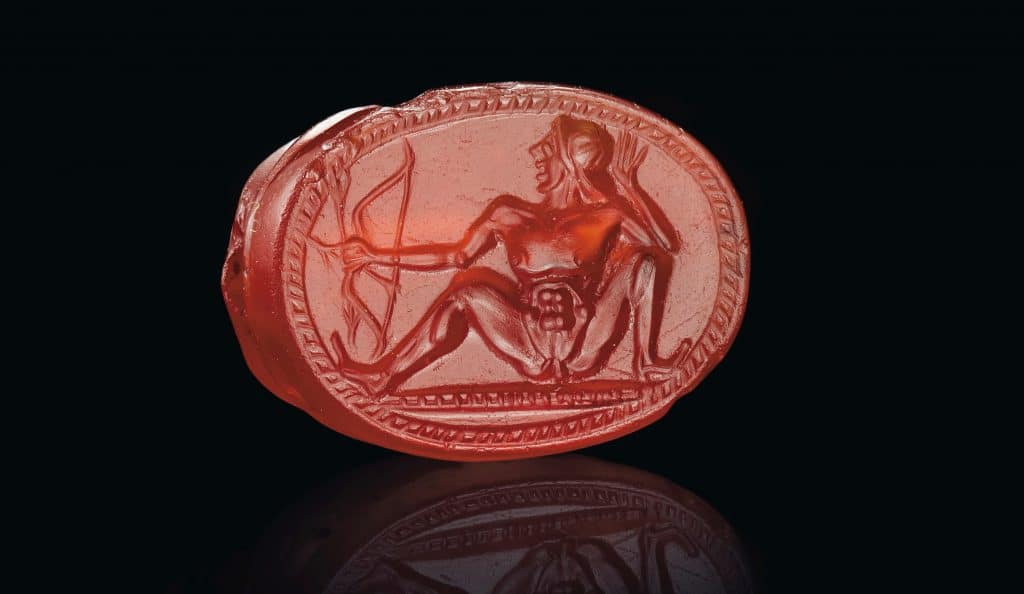

Other captivating pieces include a scarab from around 400 B.C. carved with a tiny nude archer, smiling broadly, legs splayed and pecs exaggerated, reflecting the classical concern with the body and its geometry. A gold and banded-agate ring from the same period shows Herakles carrying the remarkably articulated skin of the Nemean lion he slew — all this, mind you, on a surface that is about the size of a fingertip.

Greek carnelian scarab carved with a nude archer, Archaic Period, early 5th century B.C.

Introspective spoke with Jeffrey Spier, the senior curator of antiquities at the Getty, about the purchase of these gems and the exhibition that is giving them their first-ever public showing. The gems will be on display at the Getty Center until March 1 in an exhibition on recent acquisitions. After that they will go on display at the Getty Villa in the permanent collection galleries.

Carving precious and semi-precious stones is very delicate work, isn’t it?

Indeed. The engravers who made the most important pieces in this acquisition certainly were the best. They most likely worked in royally sponsored workshops, and their work was seen as art rather than just craft.

Is a sale of this stature rare?

Thousands of rare gems survive in aristocratic collections in places like London and Paris, and gems per se are seen at auction. But we almost never see pieces of this quality that are not fragments but are spectacularly well preserved and authenticated by having a long and illustrious provenance.

Left: The “Marlborough Antinous,” a Roman black chalcedony intaglio portraying Antinous, A.D. 130–38. Right: Greek gold finger ring depicting Herakles, Classical Period, late 5th–early 4th century B.C.

Meaning a lineage of people who owned and carefully preserved them?

Yes. This group of gems was in the collection of Roman art dealer and collector Giorgio Sangiorgi, who died in 1965. Most were acquired by him before the Second World War. For the famous stone depicting the Roman orator Demosthenes, there are extant documents that trace it back to sixteenth-century collector Lelio Pasqualini and the famous Boncompagni Ludovisi family, which includes Renaissance popes and Italian nobility. Just by virtue of who collected and admired them, we have a sense of their authenticity and quality.

Roman carnelian ring stone carved with a portrait of Octavian, mid-1st century B.C.

Which of the gems did the Duke of Marlborough own?

The Roman black chalcedony intaglio portrait of Antinous was in the Marlborough collection in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. It sold at Christie’s in London in 1875. Antinous was the favored lover of Hadrian. When he drowned at a young age, the emperor deified him, and a cult grew around his image and person. Because of its quality, this stone is often thought to be one of the most sensitive images of Antinous we have. It was likely made at the imperial court, perhaps as a gift.

Why would gems this rare and fine be offered at auction?

I cannot say exactly. The gems were brought by Sangiorgi to Switzerland in the nineteen fifties and remained there with his heirs until now.

Many engraved gems were portable seals used to imprint the owner’s chosen design into wax or clay to ratify documents and objects in a time before what we know as signatures existed. In ancient society, one of the primary objectives of engraved gems and ring stones was to serve as personal signatures or seals of identification.

Left: Roman carnelian ring stone depicting Aeneas and Anchises escaping from Troy, late 1st century B.C. Right: Greek carnelian scaraboid showing Protesilaos on the prow of a ship, Classical Period, 4th century B.C

The tradition of incising surfaces with images that would be impressed onto other surfaces is older than Greece, extending at least as far back as the cylinder seals of ancient Ur.

The idea goes all the way back to ancient Mesopotamia, some five thousand years ago, when stamp seals and cylinder seals were pressed and rolled into moist clay to sign or record something. From there, it gradually spread throughout the classical world, to Persia and Egypt, as a very specific skill of incised intaglio and raised cameo work done on gemstones used for a variety of purposes.

Etruscan gold and banded-agate scarab finger ring engraved with a figure of Herakles, early 4th century B.C.

Can you give us an example?

The rounded cylindrical seal from Bronze Age Crete, which dates to about 1600 B.C., is made from beautiful blue chalcedony and is decorated with three stunning swans — that was likely a kind of signature.

What about the gems that seem clearly intended to be worn?

Eventually, finely incised gems became objects of fashion, worn to signify class or to show the interests or allegiances of the owner.

Not to be facetious, but are you saying that gemstones bore images of ancient pop stars, like designer T-shirts today?

Quite a bit more sophisticated, but maybe remotely the same concept. Elite members of society possessed multiple gems for a variety of purposes. For example, the Roman amethyst intaglio portrait of the greatly admired Greek orator Demosthenes, depicting him balding and quite serious, that was an image people wore because they admired him or his speeches.

Left: Roman sardonyx cameo of Isis, 1st century B.C.– A.D. 1st century. Right: Roman amethyst ring stone with a portrait of Demosthenes, signed by Dioskourides, late 1st century B.C.

Demosthenes famously spoke brilliantly urging the Greeks to oppose Phillip of Macedon and his son Alexander. He was a sort of icon of national pride.

For a variety of reasons, he was very popular, and persons wore his image. Even more startling is that, at the right of the minute mustached bust, which is remarkably rendered, there is the inscription “of Dioskourides,” the artist’s signature. Today, we believe that Dioskourides was the chief gem engraver for Emperor Augustus. Dioskourides was recognized through the Renaissance and into the modern era as the greatest gem engraver of the Roman world. Peter Paul Rubens, around 1600, while visiting Rome, mentions this piece in his notes. This particular object is one of the most important gems to survive from antiquity, and now it will be at the Getty for everyone to enjoy.