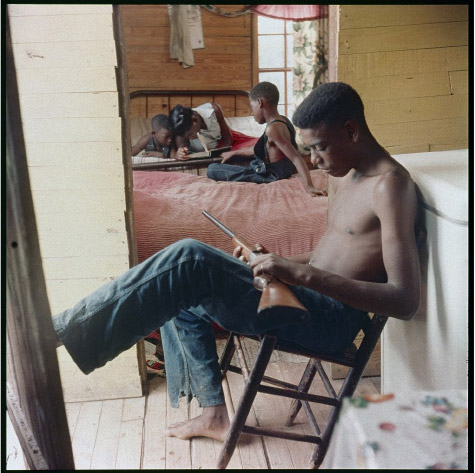

December 7, 2015Gordon Parks became famous for his work with Life, where he was the first African-American photographer on staff. Images from his 1956 “Segregation Story” photo shoot for Life are now on view at Salon 94 Freemans in New York, including Untitled, Shady Grove, Alabama, 1956 (top). All photos by Gordon Parks © The Gordon Parks Foundation.

We revere historical photographs for what they tell us about their place and time. But over the years, they can accrue new significance. That’s so for the pictures in Gordon Parks’ “Segregation Story,” on display at Salon 94 Freemans, on New York’s Lower East Side, through December 20.

The 23 works on view were culled from a larger group Parks shot in 1956 for a photo essay about the Jim Crow South for Life magazine. They depict several branches of an African-American family going about their daily lives in and around Mobile, Alabama, facing grinding poverty and “colored only” drinking fountains with forbearance and grace. When these pictures arrived in American living rooms, the civil rights struggle had just begun, and the fact that they were in color — rare for the subject matter and the time — must have given them an extra jolt of intimacy.

“We’re used to seeing images from the civil rights era in black and white,” says Fabienne Stephan, one of the gallery’s directors, “but when you see them in color, it brings them closer. It’s like a movie unrolling in front of you.”

Today, although outright segregation is behind us, a struggle for racial justice is still being waged, often aided by camera shots of all sorts, from smartphone footage to security videos. Yet the role played by photography seems quite different. Haphazardly made photos now function as evidence as well as news, whether they’re capturing the events surrounding the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, or the arrest of Freddie Gray in Baltimore. Back then, they were aesthetic objects, too, and Parks was a specialist who risked his life to bring back news from the front.

He was also a celebrity. Although his origins gave him some common ground with these particular subjects, his career took him far beyond them. Born in 1912 to a farming family in Fort Scott, Kansas, he became famous for his work with Life, from 1948 to ’72, where he was the magazine’s first African-American staff photographer, according to his 2006 New York Times obituary. He produced photo essays on such subjects as Harlem gang wars, the Black Panther party and the life of a boy in a Rio de Janeiro slum, as well as fashion spreads and portraits of celebrities like Barbra Streisand and Alberto Giacometti. Parks made his mark on American culture in other ways, too: He was the first African-American to produce and direct a major Hollywood film, The Learning Tree (1969), and helped birth the blaxploitation movie genre with Shaft (1971) and Shaft’s Big Score (1972), both of which he directed. He also helped found Essence magazine, where he was editorial director from 1970 to ’73.

By his death, in 2006, Parks, who never finished high school, had written several books, orchestral scores and a ballet and received multiple honorary doctorates. “Gordon was legendary for many reasons,” says the New York photography dealer Howard Greenberg, who works with the Gordon Parks Foundation, “but certainly for his personality. People loved Gordon.”

Parks and his local guide were constantly followed, once barely escaping a truckful of white men who’d planned to tar, feather and incinerate them.

In Department Store, Mobile, Alabama, 1956, Joanne Wilson and her niece stand in elegant attire underneath a segregationist sign.

These pictures — which despite their power languished in storage for years — weren’t made with Parks’ usual joie de vivre. The original photo essay, accompanied by text by Robert Wallace, a senior writer at Life, comprised 26 photographs and was published under the headline “The Restraints: Open and Hidden.” While capturing the photos, Parks operated under restraints, too. As he recounts in several memoirs, he and his local guide were constantly followed, once barely escaping a truckful of white men who’d planned to tar, feather and incinerate them.

“The one thing I remember Gordon saying to me about the project is how afraid he felt the whole time,” says Philip Brookman, consulting curator at the National Gallery of Art, in Washington, D.C., who organized “Half Past Autumn,” Parks’ 1997–98 Corcoran Gallery retrospective, which toured American museums until 2004.

Most of his carefully composed photographs were made with a medium-format camera inside private homes, like the gripping portrait of the patriarch and matriarch Mr. and Mrs. Albert Thornton, seated beneath their wedding picture and surrounded by photos of their ancestors. An enigmatic scene shows three children studying on a bed, guarded by an older boy with a shotgun. “Gordon told me that the family felt afraid all the time,” Brookman says.

Left: Untitled, Shady Grove, Alabama. Right: Outside Looking In, Mobile, Alabama, both 1956

Brookman also notes that many of the street scenes, likely made with a 35mm camera, were captured covertly from behind car windows. One shows an elegantly dressed woman and her niece waiting under a “colored entrance” sign. In another, a black child stares yearningly into a store window filled with white mannequins. If the photographic expedition was uncomfortable for Parks, it was even worse for his subjects. After the story appeared, the family with the studious children was stripped of their possessions and run out of town; Life later resettled them with $25,000.

Despite its importance at the time, the series slid into obscurity. Parks showed a few pictures from it, but just in black and white. Only years later, while preparing the retrospective, did he and Brookman discover a box of color transparencies. “It was a revelation,” Brookman says. For years, he added, “I never even knew they’d been published in color.” He included several in the Corcoran exhibition.

The foundation uncovered dozens more in 2011 while cataloguing Parks’ archives; eight were shown at Howard Greenberg Gallery that year. And on November 15, 2014, as a grand jury deliberated over whether or not to indict the Ferguson policeman who’d killed Michael Brown, the High Museum of Art in Atlanta opened the exhibition “Segregation Story,” comprising more than 40 pictures, some shown for the first time, accompanied by a catalogue from Steidl.

That’s where the photographer Marilyn Minter, who shows at Salon 94 and grew up in the South, happened upon the work while visiting relatives in Atlanta last Thanksgiving. And that’s how they came to Freeman Alley. “Marilyn kept texting me these images from the show,” Stephan says. “Then she called and said, ‘This really blew my mind,’ because she was as old as the kids in the pictures and she remembered those drinking fountains.” As new protests erupted in Ferguson, the gallery decided it made sense to present the work in a contemporary-art setting.

“It’s important to keep Gordon’s work alive in the eyes of a young audience,” Stephan says. “In this era of everyone being able to snap a quick picture wherever they are, his photographs take on a whole new meaning.”