Hayden Herrera’s latest biography is Listening to Stone: The Art and Life of Isamu Noguchi (photo © Blair Resika). Top: Herrera’s subject, seen in his studio in Gentilly, France, in 1928 (photo by Atelier Stone).

Back in the 1970s, when Hayden Herrera began researching a book on Frida Kahlo, she explains,“Kahlo was seen in Mexico as Diego Rivera’s sort-of-peculiar wife with the strange little paintings that most people really didn’t like very much. And in the United States, almost no one knew who she was.” Published in 1983, Herrera’s Frida, which was the basis of the 2002 Julie Taymor biopic starring Salma Hayek, is credited with helping to set in motion Fridamania, which has made the artist a household name and immortalized her as a feminist icon.

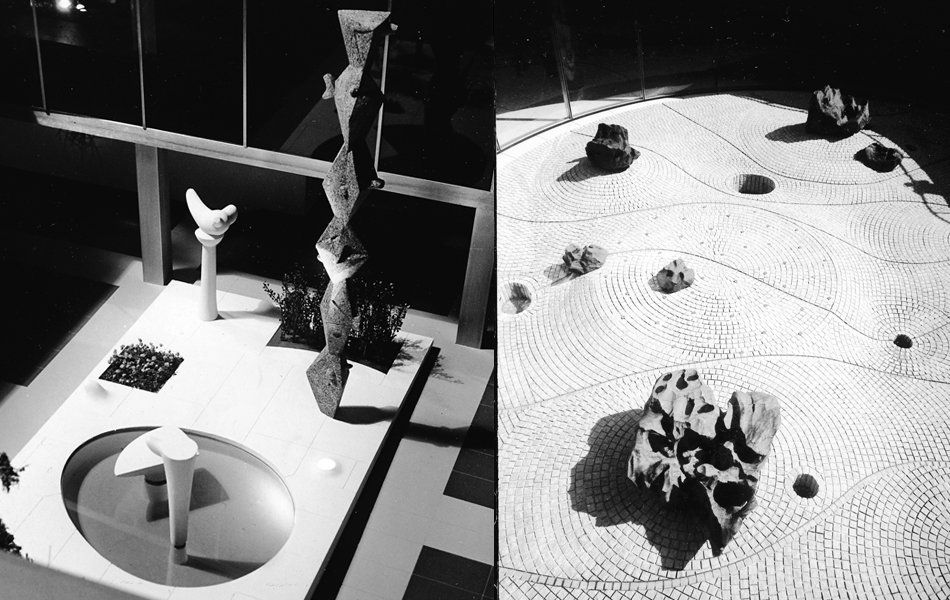

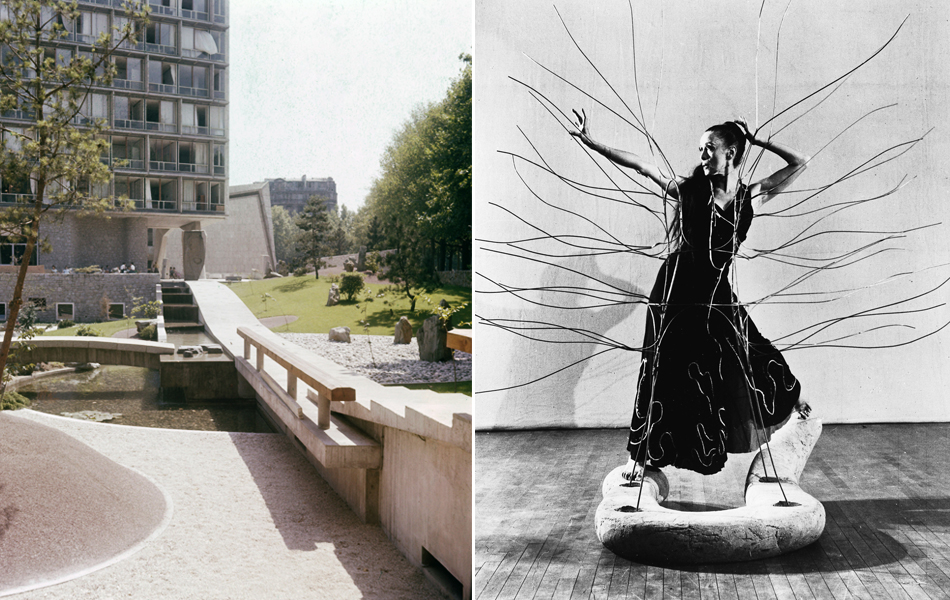

Frida was followed by biographies of Henri Matisse and Arshile Gorky (which was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize). Now, Herrera’s latest book could have the power to transform the reputation of another relatively under-appreciated artist: Isamu Noguchi. Listening to Stone: The Art and Life of Isamu Noguchi (Farrar, Straus and Giroux) has been welcomed as a much-needed portrait of one of the most inventive artists of the 20th century, one who has nonetheless remained an elusive figure, surprisingly little known. Perhaps because this Japanese-American artist worked prodigiously in so many fields, he’s particularly difficult to pin down: a talented sculptor known for his biomorphic forms in stone and wood, he also designed landscapes (among them gardens and playgrounds), theater sets, costumes and, notably, furniture — creating iconic tables for both Herman Miller and Knoll, as well as his perennially popular paper-shaded Akari lighting.

The Brooklyn Botanic Garden is currently presenting a garden-wide exhibition of Noguchi sculptures. In conjunction with the installation, which can be seen until December 13, the BBG has scheduled special programming, including a public talk on Sunday, November 8, with Herrera and Dakin Hart, senior curator of the Noguchi Museum, in Long Island City, Queens, which has collaborated on the show. Here Herrera speaks with Introspective about the man, the mythology and the making of her latest book, for which James Paterno, writing in the New York Times, thanks Herrera for “helping all of us walk beside this ‘nomad’ who ‘sought and found, by making sculpture, a way to embed himself in the earth, in nature, in the world.’ ”

Noguchi at work in 1950 on the plaster original of Mu, a seven-foot-tall sculpture whose name is the Zen term for “nothingness” or “emptiness.”A later version, carved in stone, was installed in a garden at Tokyo’s Keio University.

What made you want to write about Noguchi?

Interestingly, he was one of Gorky’s closest friends, and he and Frida had a love affair in the 1930s and remained good friends until the end of her life. I liked that triangulation among the three artists, and it made me feel in some way connected to him. I was also drawn to Noguchi because all his life he felt an outsider — Japanese when in America and American when in Japan. Growing up, I spent a lot of my childhood being shuttled between Mexico and America and experienced a very real sense of never quite belonging.

How long did it take you to write this book?

Believe it or not, almost ten years, although I have to admit that all my books have taken me that long. I am a slow reader and an even slower writer! It also takes a lot of time to understand an artist. At first, I found the notion of writing Noguchi’s biography to be quite daunting. Even though he wanted his life to be recorded, Noguchi was a man who did not seem to want to be known. In that way he was so unlike Frida, whose art is so autobiographical and passionate, and Gorky, whose paintings are so emotionally charged. Noguchi was famous for his charm, physical beauty, brilliance and powers of seduction, but friends always said he was exceedingly private, even remote. And his work, however beautiful, does not give much away.

Noguchi’s Energy Void, photographed in 1971 at the Noguchi Museum in Japan, was originally commissioned for the famed sculpture garden at PepsiCo’s corporate headquarters in Purchase, New York. Herrera writes that Noguchi thought “it was possibly the best sculpture he had ever made,” so he kept it and created a different version for PepsiCo. Photo by Michio Noguchi

Did you ever meet Noguchi?

Yes, in 1978, I interviewed him about his relationship with Frida Kahlo, and he took great delight in telling me one of his favorite stories — how he had once been in bed with Kahlo when her houseboy warned them that her husband, Diego Riviera, was on his way. Noguchi threw on his clothes, ran into the garden, climbed a tree and escaped over a roof. But Kahlo’s dog had made off with one of his socks and when next he saw him, Rivera, who had discovered the incriminating evidence, threatened to shoot Noguchi. Years later, when I was told that Noguchi had said he wanted me to write his biography, I guessed that maybe this was because he liked my retelling of that story.

Many people know more about Noguchi’s furniture and Akari lamps than about his sculpture. What does this tell us about the artist?

Noguchi always said that he hoped to be remembered not for a particular body of work but for contributing “something to an awareness of living.” He believed strongly in the Japanese tradition of not making any division or distinction between art and craft and saw his lamps and tables as an integral part of his work, growing defensive if accused, as he sometimes was, of being too commercial. He also crossed other disciplines — making sets for Martha Graham and designing gardens. Noguchi felt that if he lost a child’s sense of wonder, he would stop being an artist, and a huge disappointment was that none of his five designs for playgrounds — one of them a collaboration with Louis Kahn — was ever realized.

Noguchi, in his Queens, New York, studio in the 1960s, sits among his paper-and-bamboo Akari lamps. The space is now a museum.

Where do you see his place in the world of 20th-century art?

I think Noguchi and David Smith were the greatest sculptors of their generation, but Noguchi remains outside the mythology of the New York art world, and as a result he has been dreadfully neglected. In spite of being friends with many of the artists then working in New York, he was always picking up and leaving to go live in Paris or Mexico or Japan. The quietness of Noguchi’s art is quite different from the work of most of his contemporaries, and his sense of not belonging, which drove his art and was with him all his life, also sets him apart and makes his work hard to categorize.