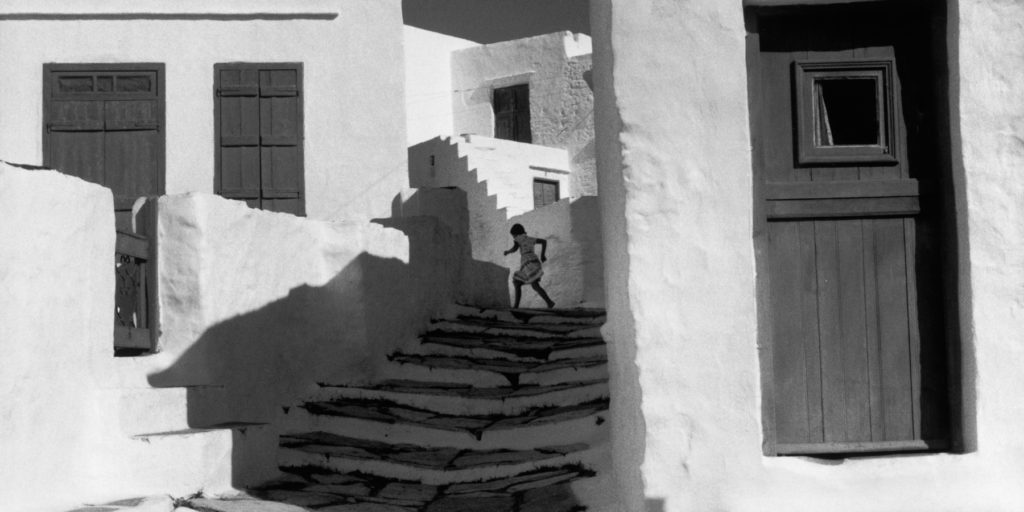

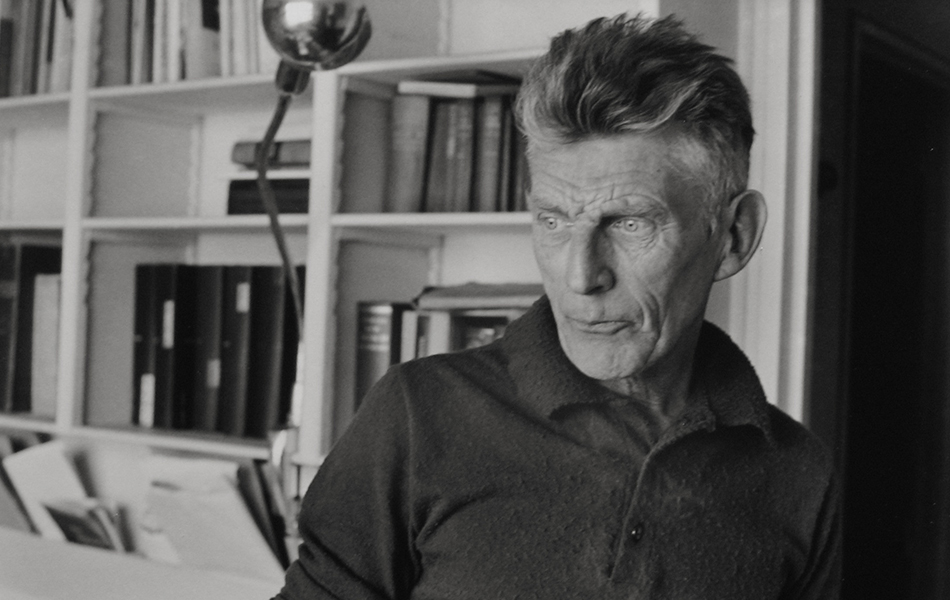

The late photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson spent his long and varied career traveling the world and capturing images of everyone from children to cultural icons (portrait © Estate of Sam Tata). A retrospective of Cartier-Bresson’s work at Peter Fetterman Gallery, in Santa Monica, California, contains a wide variety of images, some of which were printed at the gallery’s request. Above: a portrait of the photographer, ca. 1940, by Sam Tata. Top: Île de Sifnos, Grèce, 1961. All photos © Foundation Henri Cartier-Bresson / Magnum Photos, Courtesy Peter Fetterman Gallery, unless otherwise noted

Regardless of nationality, young children seem to enjoy many of the same pursuits: They like to run at full speed, pull toy trains along the ground so they make maximum noise, grasp the hands of friends. At least that’s true in the street photography of Henri Cartier-Bresson, in which he captures children from different countries and economic classes engaged in the same sorts of activities. Whether they are wearing torn clothes or new parkas, many of the kids in his pictures are busy playing to the point of being oblivious to the camera and photographer. Some are playing in the streets; others are playing at being adults. Beautiful but unsentimental photography of children is one of the surprises offered by the sweeping survey “The World of Henri Cartier-Bresson,” at Peter Fetterman Gallery, in Santa Monica, California, through December 3. The show contains more than 100 images from Fetterman’s own collection, all signed by the artist.

Some of the images are iconic, like Cartier-Bresson’s historic 1950s photographs for Life magazine of a newly Communist China and his portraits of cultural lions like Henri Matisse, Alberto Giacometti and Samuel Beckett. But nearly half the images, Fetterman says, were printed specifically at the gallery’s request and have not been widely exhibited or published. One of the most striking discoveries is a 1954 image of five Russian girls standing in second position at a wrought-iron-and-wood ballet barre. The coolly elegant blond girl closest to the camera looks no more than 10 or 12 years old, but her calf muscles are as defined as those of an adult track star.

Rue Mouffetard, Paris, 1954, Cartier-Bresson’s famous photo of a boy proudly strutting with a bottle of wine under each arm, is an example of capturing “the decisive moment,” a term he coined.

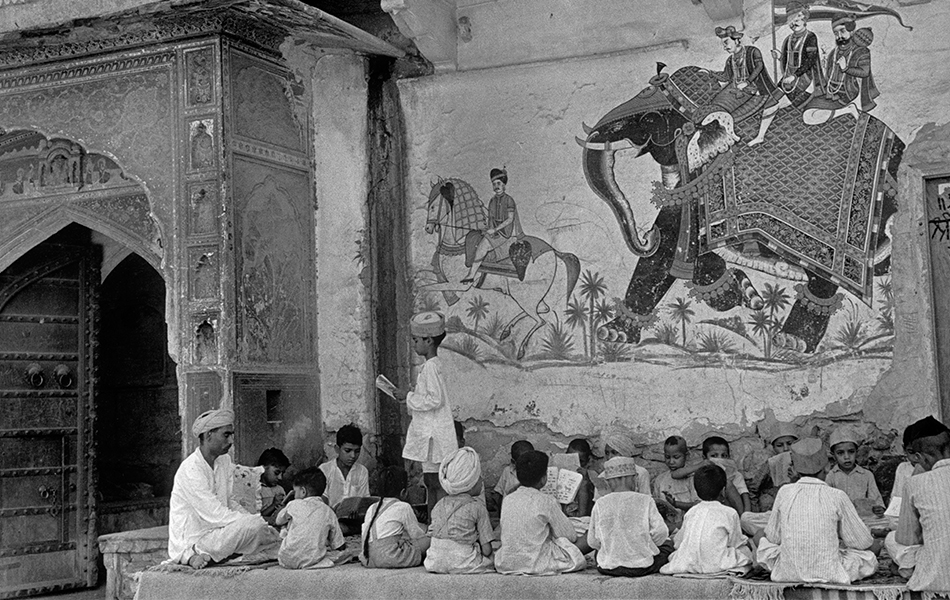

The show also contains the powerful and little-seen Pavement School, Jaipur, India, from 1948, showing schoolboys crowded together on the pavement underneath a large crumbling mural of a regal elephant: Most of the boys look soberly at their books, as they were evidently instructed to do; one is caught boldly peering over the top of his at the camera. Shot in the photographer’s home country, site of his legendary views of formal gardens, Lorraine, France, 1959, shows two boys flying through the air in the jet-like car of a carnival ride. Their stern, bracing expressions manage to say both “I’m not scared” and “I’m terrified.”

Among the more celebrated pictures, Rue Mouffetard, Paris, from 1954, captures a boy grinning from ear to ear as he walks along a city street toward the lens — and presumably toward home — carrying with chin jutted out and visible pride a wine bottle under each arm. This picture, in which all elements conspire to highlight the boy’s swagger (notice the girls noticing the boy), is an illustration of capturing “the decisive moment,” which Cartier-Bresson famously defined and which modernists took as the ultimate goal of photography, although others later were more skeptical.

Cartier-Bresson took this image, Marilyn Monroe, 1960, while the actress was filming The Misfits in Nevada.

In an essay for his 1952 book The Decisive Moment, which was beautifully reprinted in facsimile form by Steidl last year, Cartier-Bresson wrote that the essence of photography is “the simultaneous recognition, in a fraction of a second, of the significance of an event as well as of a precise organization of forms which give that event its proper expression.” Others might call this poetry, under the definition of a poem as prose in which a single word cannot be altered.

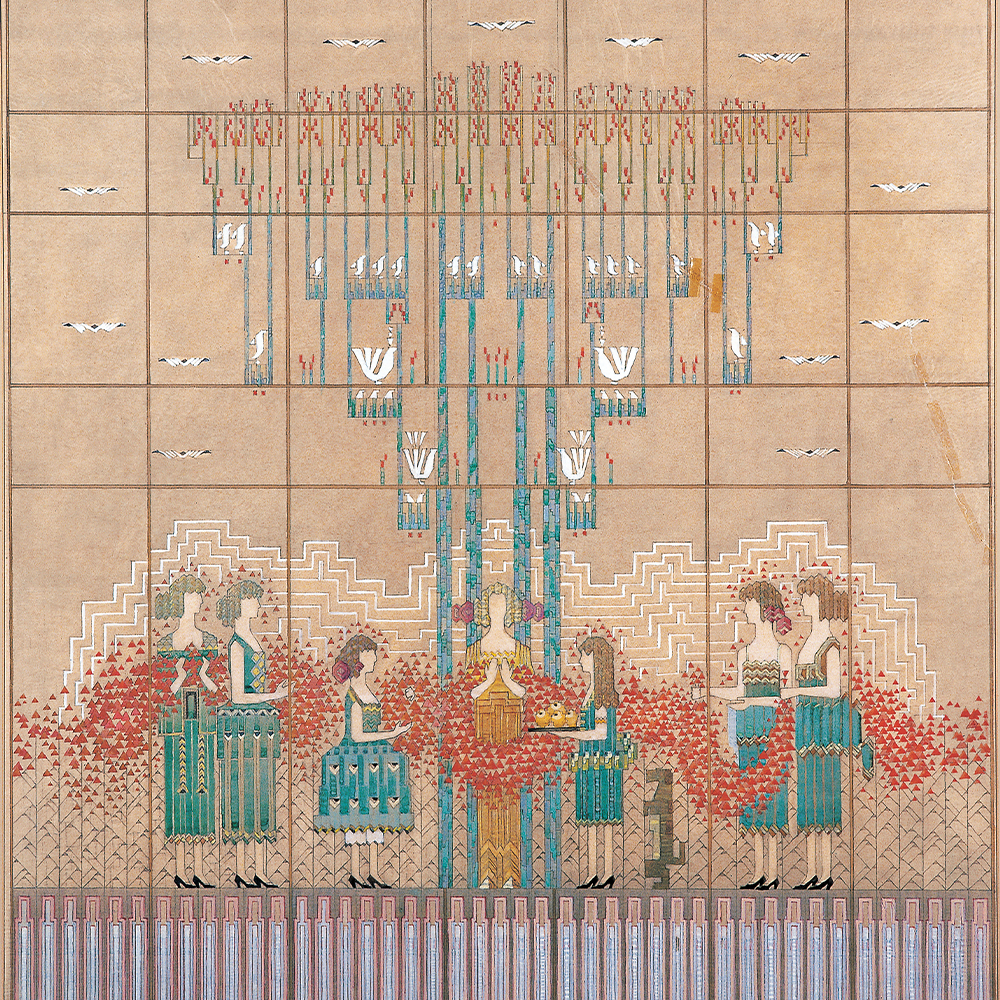

Born in 1908 in Chanteloup-en-Brie, France, the oldest of five children, Cartier-Bresson studied art and literature in school, refusing to join his father’s prosperous textile business. In 1931, he traveled to Africa to hunt wild game and found that he preferred a different kind of shoot: taking pictures with a small box camera. On his return to France, he bought a Leica with a 50mm lens — the camera he called the “extension of my eye” and used for decades. He soon began working as a photojournalist, traveling the globe to capture everyday moments as well as some of the defining political events of the 20th century, from Gandhi’s funeral in 1948 and the fall of the Kuomintang in China in 1949 to the student uprising in Paris in 1968.

Cartier-Bresson was himself caught up in conflict. A French army officer during World War II, he was detained as a prisoner of war by the Nazis, prompting rumors he’d been killed. His photography was taken seriously enough at this time that the Museum of Modern Art in New York began preparing what it believed would be a posthumous retrospective of his work. The show took place in 1947, when the photographer was abundantly alive and well, and busy cofounding the great photo agency Magnum. MoMA has been a guardian and champion of his work ever since.

Fetterman says Cartier-Bresson was the reason he began collecting seriously before he opened his gallery: His initial purchase was the photographer’s stark 1948 image of Muslim women praying in Srinagar. Fetterman first met Cartier-Bresson when visiting Paris in 1993 on gallery business. “He was notoriously difficult with dealers, not giving them a discount,” Fetterman says. “He just didn’t need fame or money. But I found him charming. He was so well-read, so erudite. You would visit his apartment, and he would be listening to Bach.” Fetterman found the courage to ask Cartier-Bresson about images that weren’t yet printed for sale, pointing, for example, to a tiny image of the young ballerinas at the barre in the photographer’s 1955 book The People of Moscow.

“I would say: ‘Why haven’t you made a print of this? It’s such a beautiful, lyrical image,’ ” the dealer relays. “He would say: ‘Peter, nobody’s ever asked.’ ” Fetterman says this kind of exchange took place repeatedly over the following decade before the artist’s death at age 95 in 2004. “I would ask him kindly to make three images, two for me to sell and one for me to keep for myself,” he notes. So why is he parting with the prints he once reserved for himself? Fetterman describes it as a case of the dealer in him winning out over the collector: “You come to a certain point, or maybe a certain age, when you cannot hold onto works like these anymore. I felt it was time to find new homes for them. And I wanted to make a statement by bringing them all together — a sort of swan song to a bygone era.”