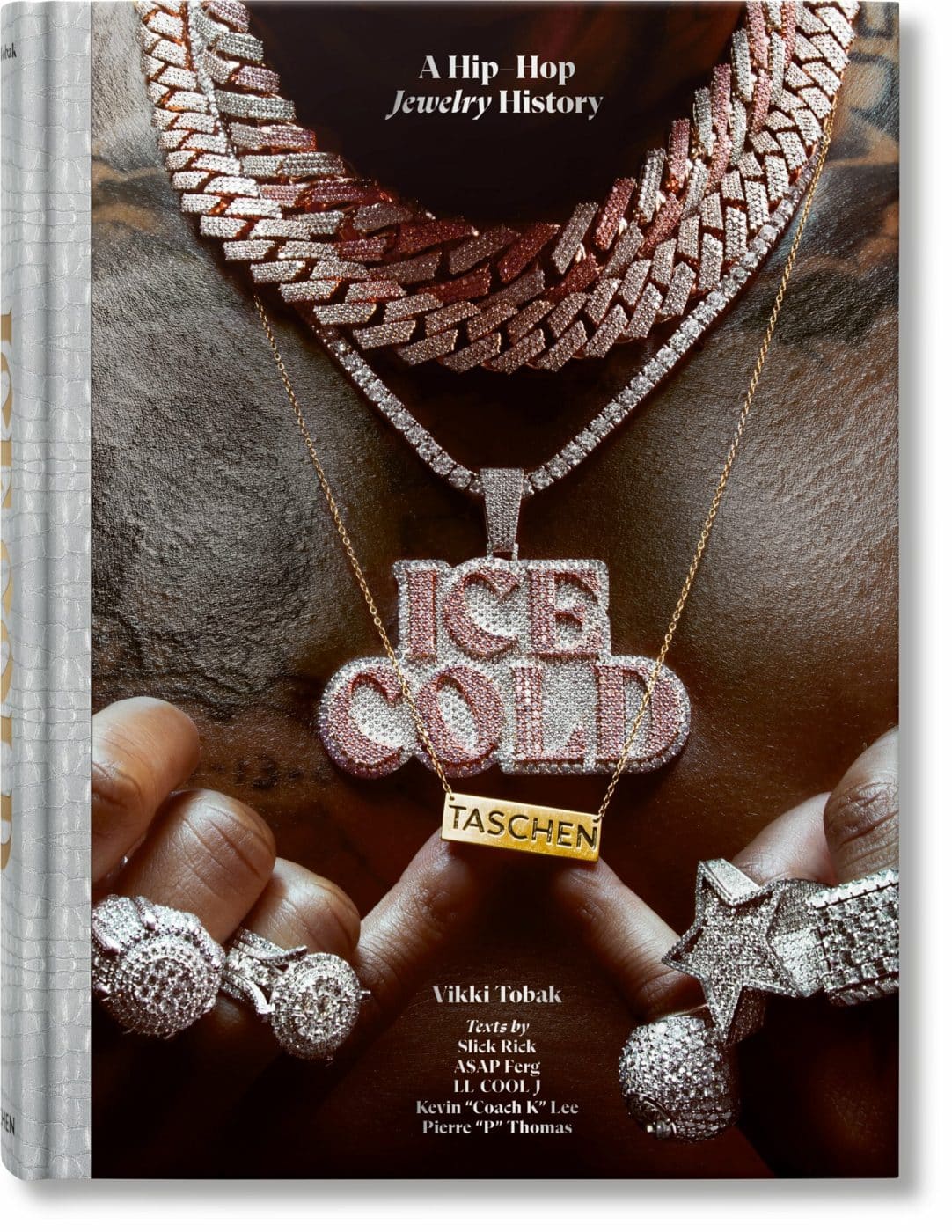

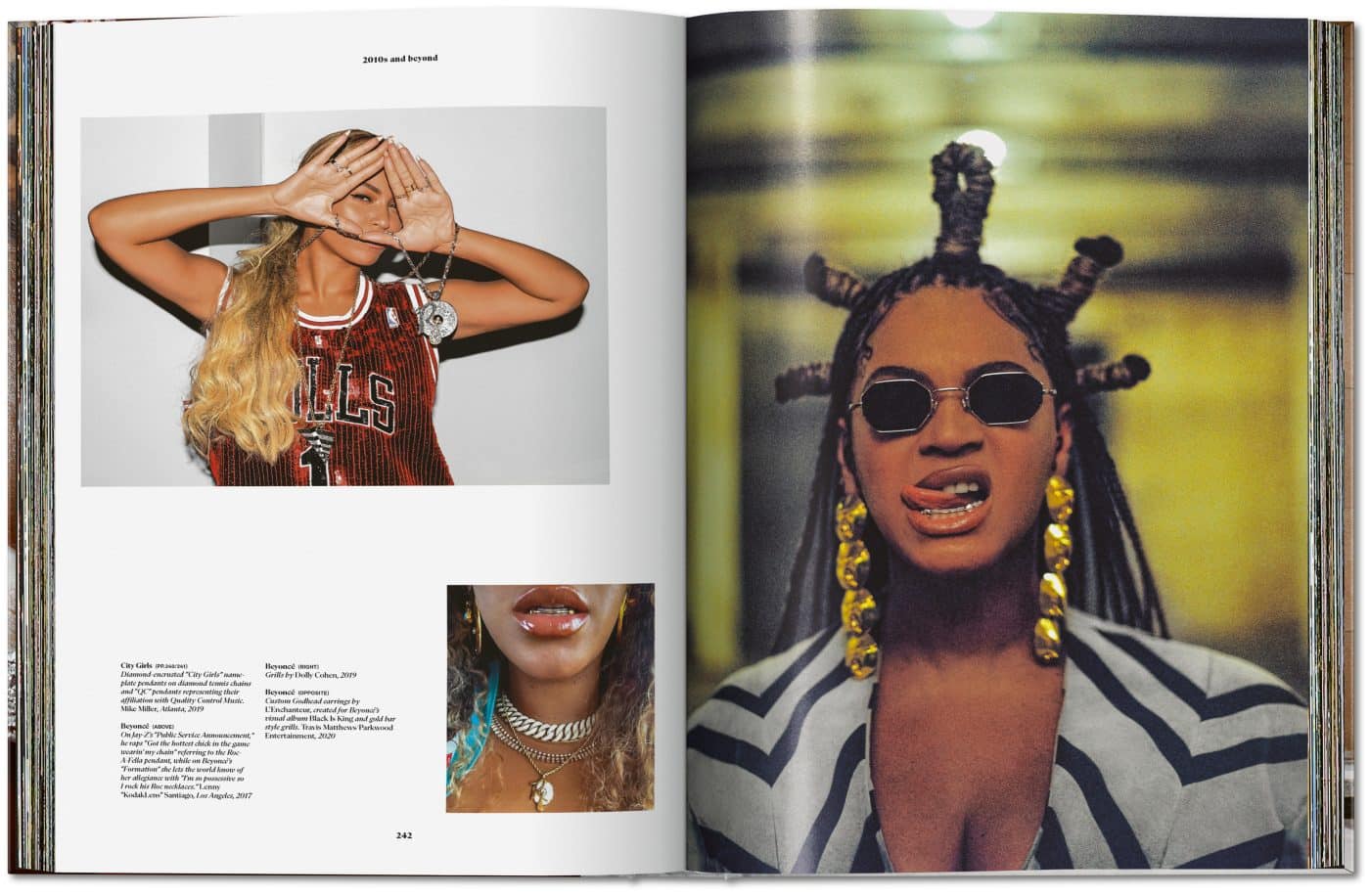

October 23, 2022Without hip-hop, there would be no bling. That’s the thesis journalist Vikki Tobak sets out to explore in Taschen’s new Ice Cold: A Hip-Hop Jewelry History. And explore it she does. Through 40 years’ worth of portraits, plus accompanying text, the lavish volume paints a dazzling picture of the style of greats from Jay-Z and Beyoncé to Lil’ Kim, Rihanna and A$AP Ferg, as well as those of the jewelers who outfitted them — Jacob Arabo, Tito, Greg Yuna and more — for whom success can be measured in carats and commissions.

The jewels worn by hip-hop artists has the ability to tell stories about Black life in America — ones in which “the industry’s aristocracy . . . of rappers, label heads, entrepreneurs, and street hustlers alike reimagined the age-old cycle of power with jewelry as their mode of communication,” Tobak writes. “Like the music, the hip-hop jewelry game has always been competitive, bigger and bigger until you reign supreme.”

Think of LL Cool J — who penned an essay for the book — known for his layered gold rope chains and nameplate ring spelling out “James” (his first name). Or consider Biggie Smalls, with his iconic Jesus pendant. And let’s not forget Jay-Z, known to err on the low-key side with a white tee and a platinum Rolex — a subtle flex if ever there was one.

Then there are the ladies: Today, just look at Nicki Minaj and her custom “Barbie” pendant on a diamond tennis chain, or Megan Thee Stallion, whose “Hot Girl” pendant and diamond-encrusted flames-link chain were made with a cool 155 carats of diamonds and a kilo of gold.

Divided into decades — and available in three versions, two accompanied by fine-art portraits of artists signed by the photographers — Ice Cold charts jewelry’s rich role in hip-hop, starting in the 1980s with the emergence of “truck” jewelry (gold pieces in astonishing weights) and logos hanging from chains. The ’90s saw more ostentation: diamond-and-platinum three-finger rings, as well as crosses, an enduring symbol of the genre.

Hip-hop’s next wave was emboldened to think bigger and flashier. And thanks to the 1998 hit “Bling, Bling” by the Cash Money Millionaires (“Everytime I come around yo city / Bling bling / Pinky ring worth about fifty / Bling bling”), the phrase infiltrated pop culture — it was officially added to the Oxford Dictionary in 2003. Bling’s where the jewelers come in.

In 1999, the New York Times dubbed “Jacob the Jeweler” Arabo, of Jacob & Co., the “Harry Winston of the hip-hop world.” He was swiftly joined by the likes of Iceman Nick, Avianne & Co. and Icebox — all of whom, Tobak writes, “started laying the foundation for a new generation of jewelers with a vision to match hip-hop’s ‘sky’s the limit’ outlook.”

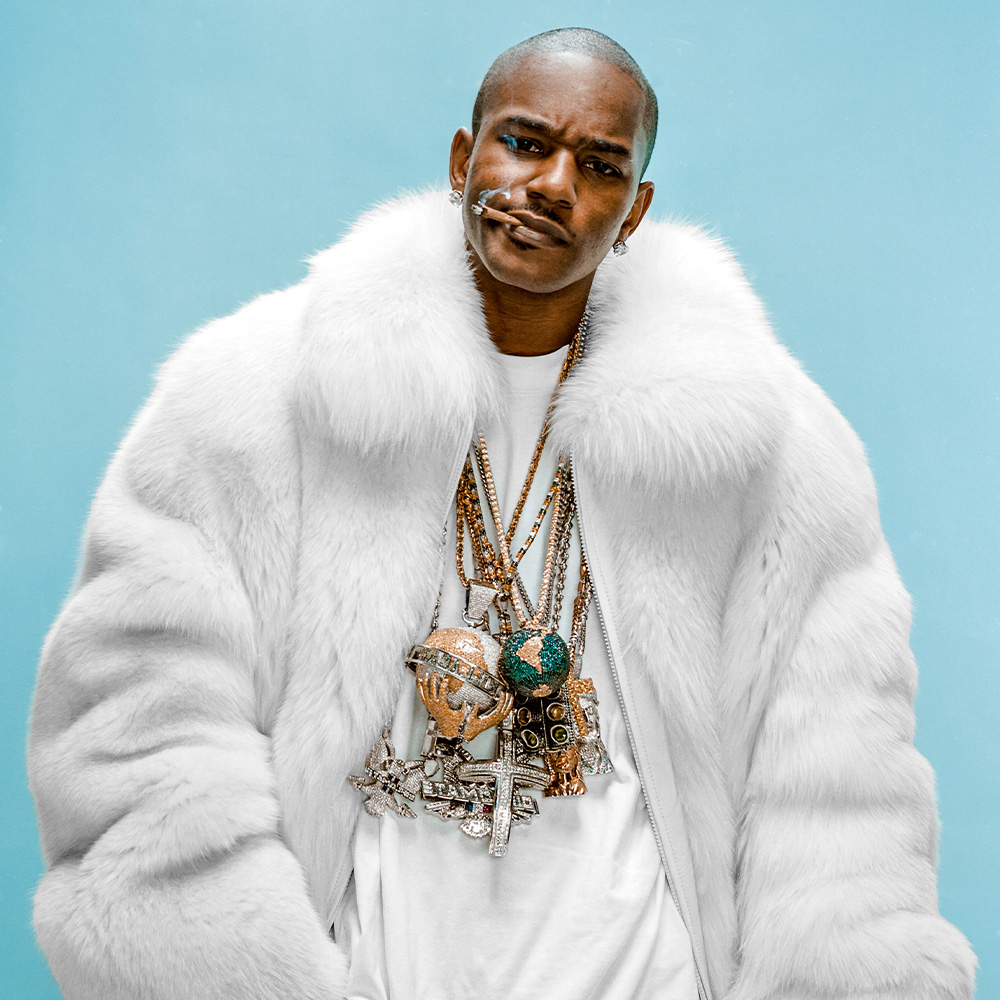

The artists themselves began bringing a more distinct point of view, with bespoke commissions that shifted gender norms well before Timothée Chalamet and Harry Styles came along. In the 2000s, Pharrell Williams‘s playful aesthetic ushered in a vogue for multicolored-gemstone designs by Jacob & Co., among others, and in the late 2010s, A$AP Rocky broke out beyond traditional gold, platinum and diamonds to wear pearls — a nod to the royal dress of the maharajas.

As for where that all leaves us today, Tobak concludes that “[b]ling still denotes status in hip-hop, but now it’s about a more expansive view of what hip-hop is.”

In other words, bling — like hip-hop itself — has cemented its crossover appeal, even if it hasn’t gone entirely mainstream. Tiffany & Co. tapped A$AP Ferg, who also wrote one of the book’s essays, as the brand’s first hip-hop ambassador in 2018. (Jay-Z and Beyoncé came later.) And Wolfgang Tillmans photographed Frank Ocean shirtless in the shower wearing a stud in one ear and a pair of rings on his pinky. That portrait is now on view at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Tobak suggests that even as the culture shifts, bling is here to stay. “The art of adornment is part of our shared human history,” she writes. “[It] taps into our deep psychological need to show up and show out.”