January 31, 2021In 1985, when contemporary art dealer Ivy Brown moved into the live-work loft space in Manhattan’s Meatpacking District that now houses her eponymous gallery, slaughterhouses and refrigerated trucks lined the cobblestone streets. “It was a very different place,” Brown recalls. “We had three S and M clubs in the building and the largest transvestite supply shop across the street.”

Brown watched the blocks around her transform through the many windows of her triangular loft, which occupies the third floor of an 1880s flatiron-shaped structure just below 14th Street. Chic boutiques and world-class restaurants sprang up, eventually followed by the High Line, one of the city’s most popular parks, and the Whitney Museum of American Art.

Born in New York City, Brown moved to London with her family at the age of 12 and took classes at the Camden Art Centre before returning to Manhattan in the early 1980s to study art therapy at the School of Visual Art. After taking a detour as a makeup artist, she landed in New York’s vibrant downtown fashion scene, producing fashion shows at the city’s most happening nightclubs and working in television (one particularly memorable project was a Ramones video for Andy Warhol’s TV production company).

Before long, Brown had launched an agency representing the stylists, photographers and other creatives she had worked with, and in 2001, she turned part of her vast loft into an anything-goes collaborative space for them. It was a prelude to her art gallery. Around the same time, she decided to also use her production skills for the civic good, joining forces with the neighborhood’s few other full-time residents to persuade the city to landmark the neighborhood as a historic district, which it did in 2003.

“We stopped developers from building skyscrapers above the old meatpacking houses — they can only build four stories, not twenty,” she says. But Brown is not entirely against the changes in the district. “I think people should be able to sit outside at cafés and bars and have a drink if they want to. And it’s phenomenal to have the Whitney Museum in your backyard!”

Today, Ivy Brown Gallery still emits an aura of authentic, historical New York City cool. But Brown, who shares the loft’s living space with her husband, is noticeably forward-thinking when it comes to contemporary art. She experiments freely with exhibition formats, and her stable of artists reflects a commitment to fostering innovative work.

Brown spoke with Introspective about her unconventional path to becoming a gallerist, her love of carefully made objects and the joy of sharing art with people.

You took a different path to dealing art than many others do. Can you tell me about the evolution of your gallery?

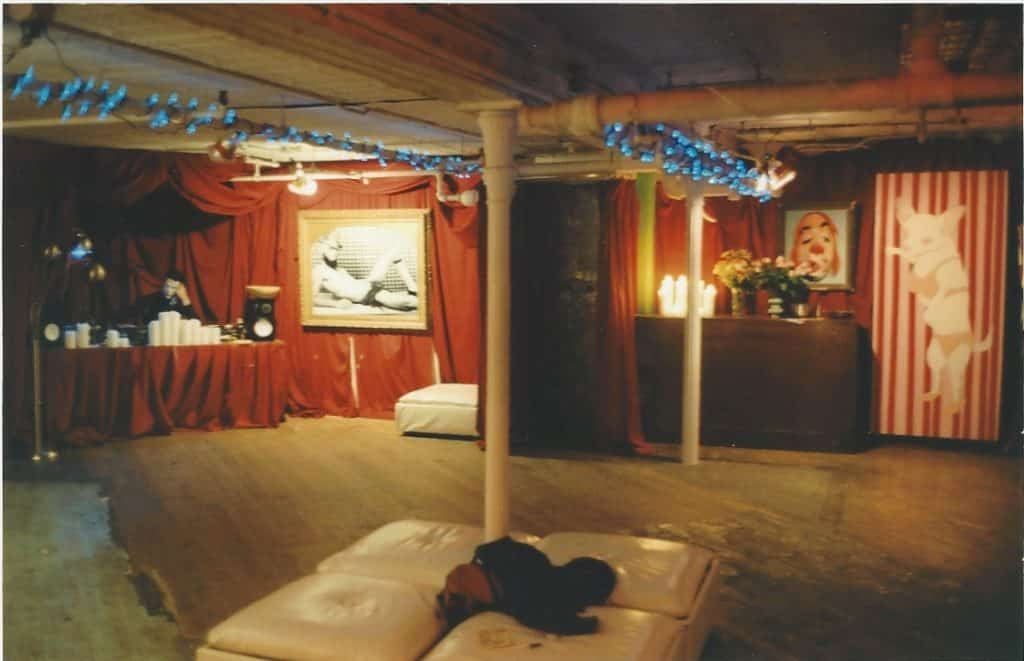

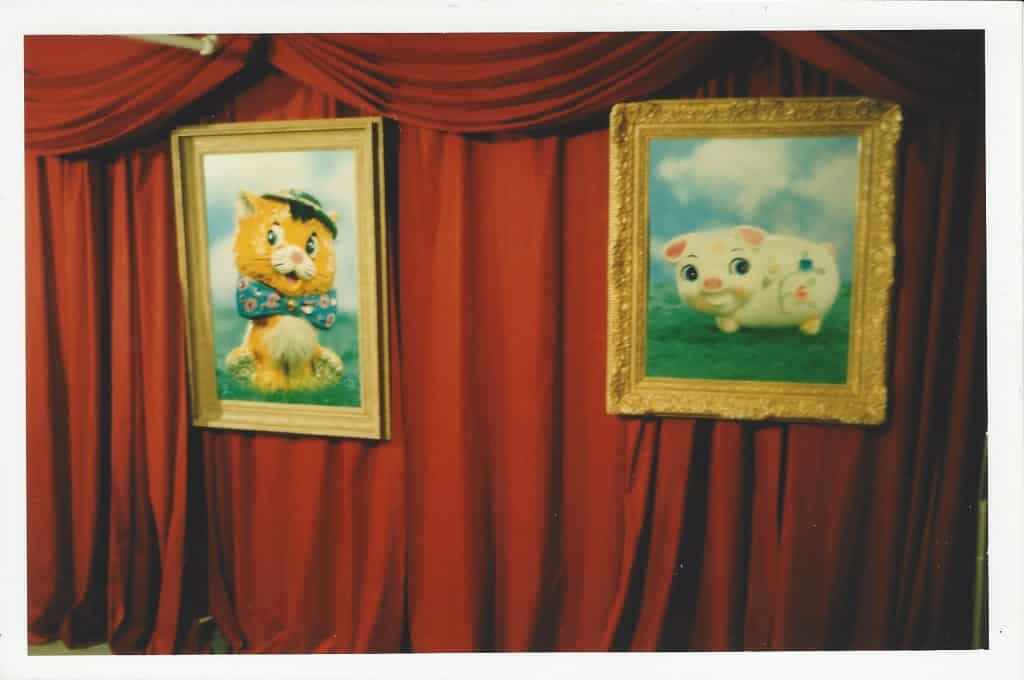

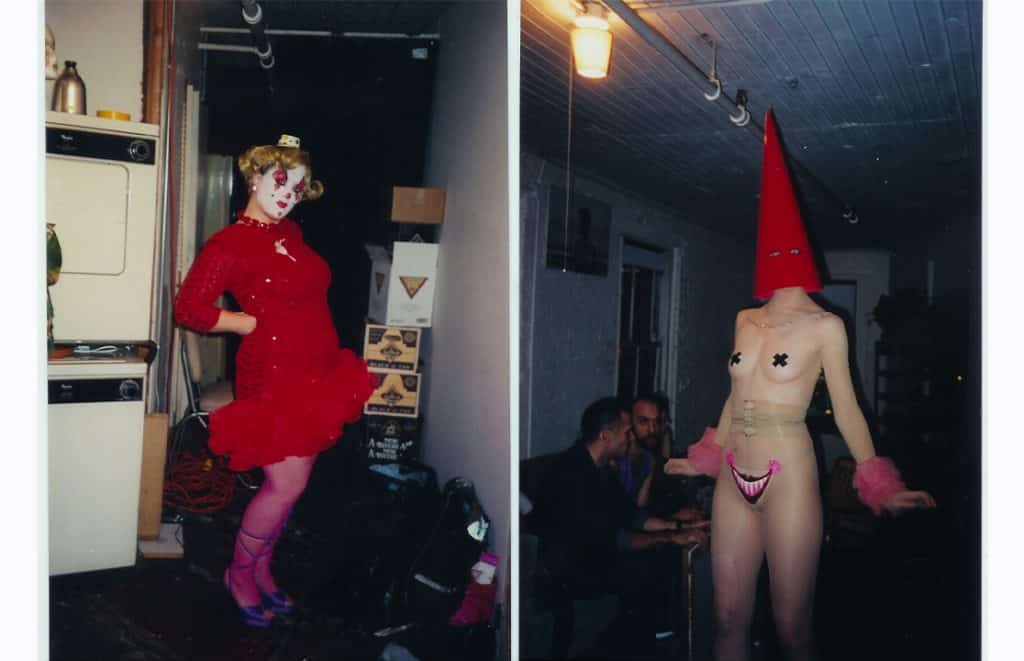

The gallery was first meant to be a creative playground. I used to represent photographers and set stylists commercially in fashion and advertising, and they’d create these phenomenal environments. It was so much fun. There was so much space in the loft, so I decided to set up a place with them where we could be creative, where we didn’t have clients to answer to.

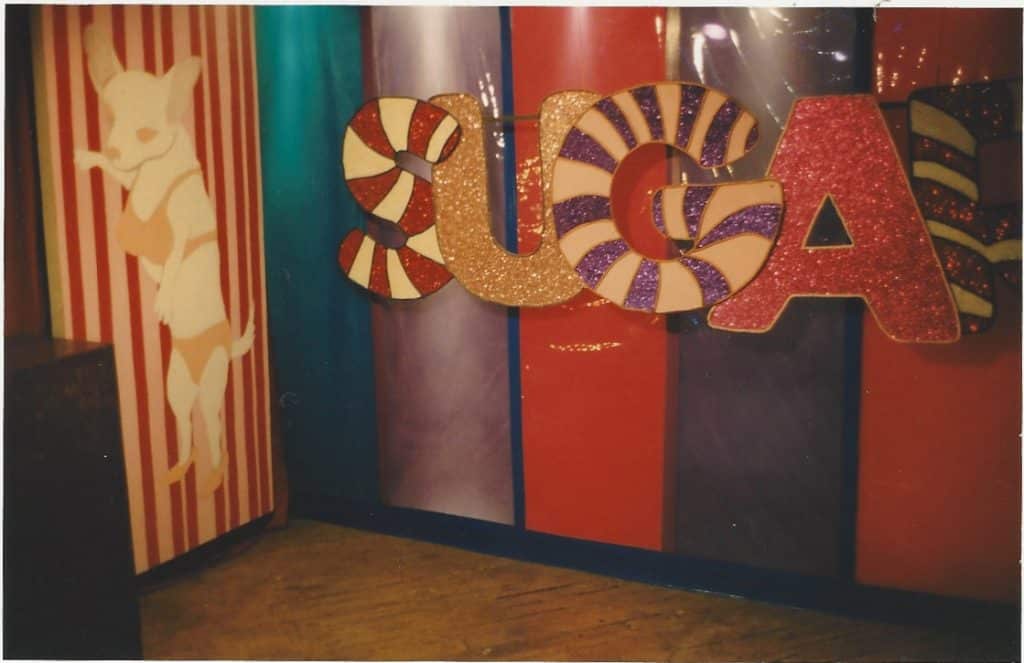

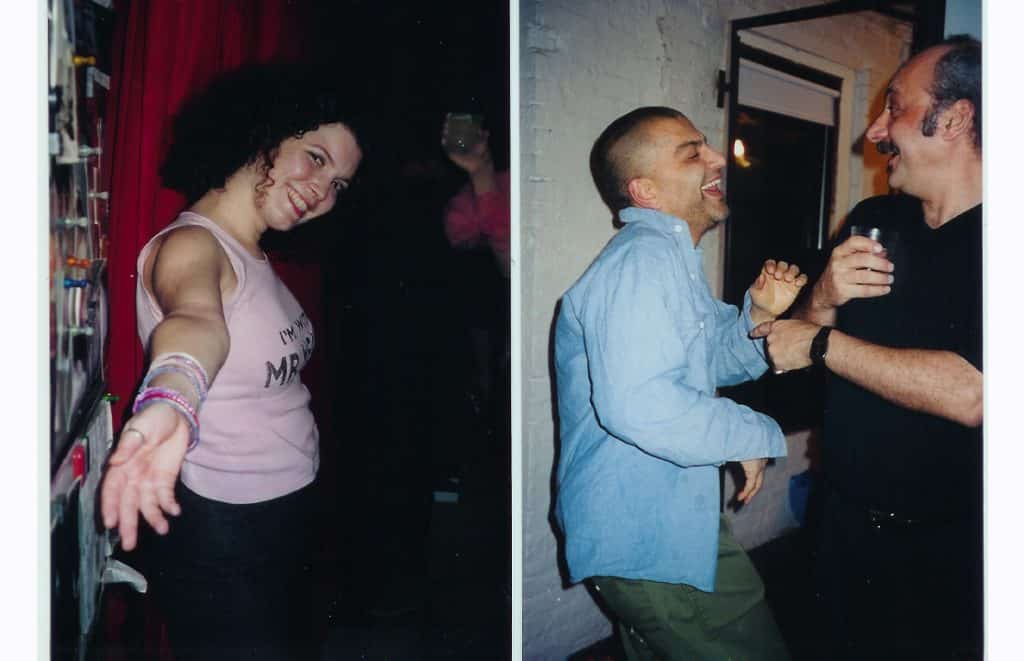

We opened in November of 2001, a few months after 9/11. We had nine performance artists, and more than six hundred people showed up. It was absolutely wild. The space was then called Go Fish, and it evolved into Ivy Brown Gallery as the company grew up.

Your tagline reads “Bringing unusual art to the people.” What do you mean by that exactly?

I look for my collector base to be very vast, which is why I have a variety of work in a big price range. I want people at all levels to be able to appreciate art and own art.

What gets you excited about an artist’s work?

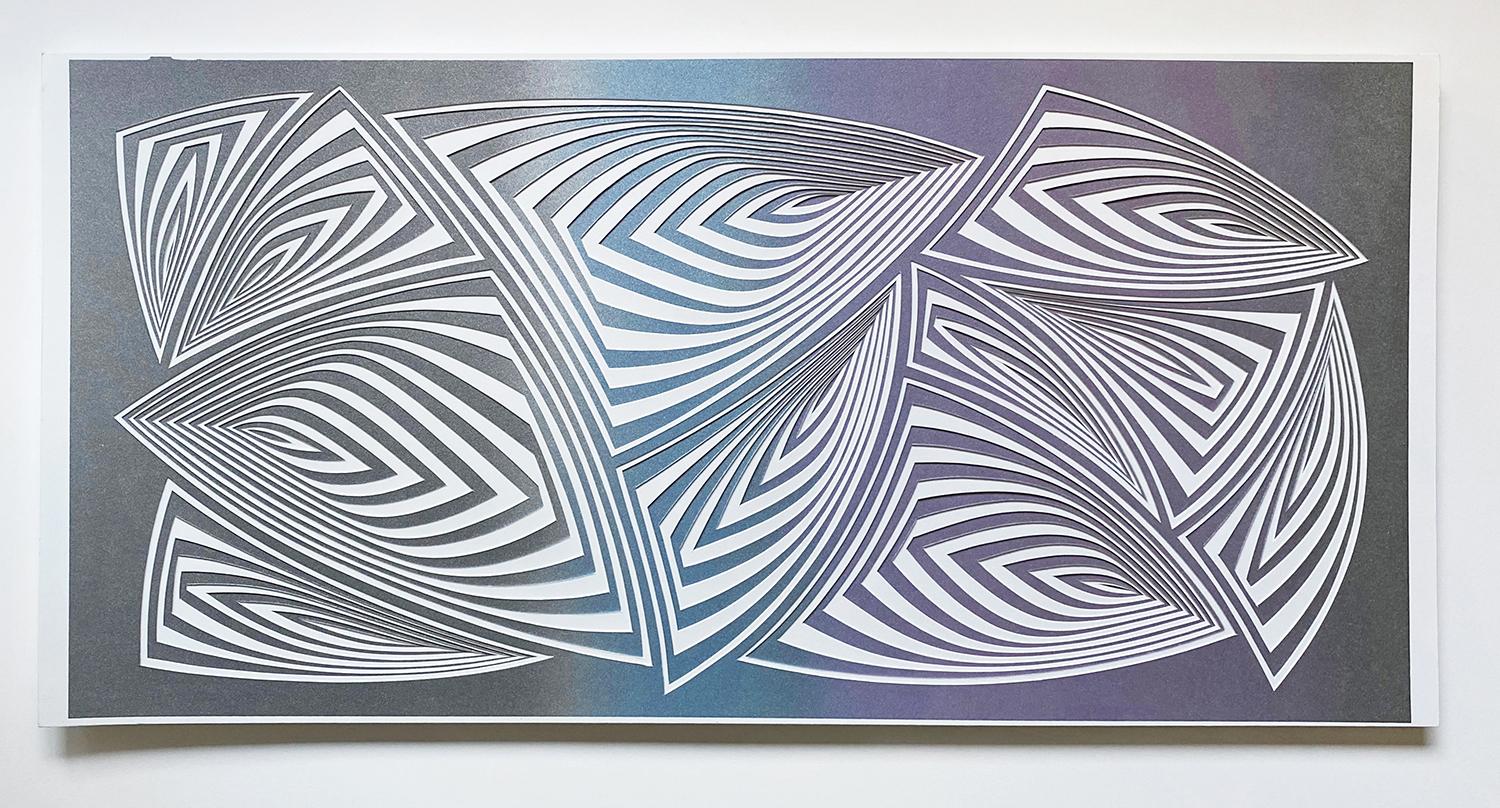

I like things that are well crafted and that have a classic and timeless element with a twist. One of the joys of my job is seeing work that I love and being able to show it to other people. Right now in the gallery, for example, we’re showing Elizabeth Gregory-Gruen, who uses a surgeon’s scalpel to cut through two-ply museum board to make her “paintings.”

She doesn’t use any line drawings — she does them freehand. She goes through around one hundred blades per work. And she works with a master silkscreener, Gary Lichtenstein, to print the color on the boards before carving them. She was a fashion designer previously and worked for Michael Kors, doing coats. So she’s got a very steady hand.

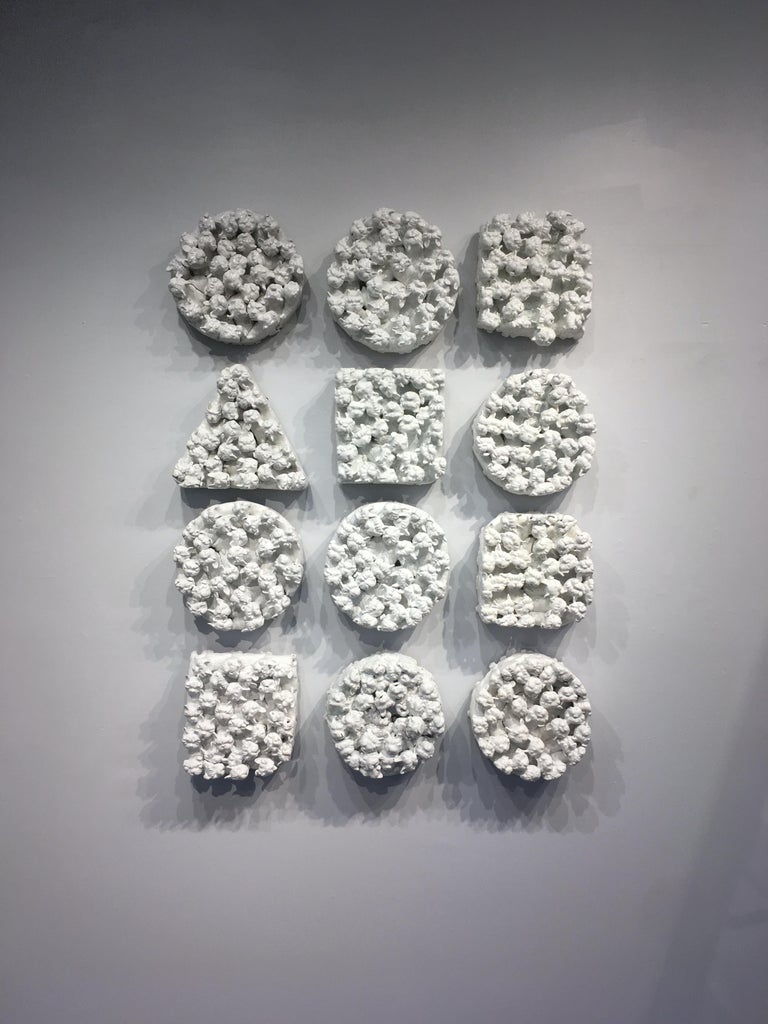

Her work is very tactile, like that of many of the artists you show. Are you especially drawn to this quality?

I am especially drawn to the three-dimensional. I studied sculpture, and I love working with my hands. And I love being able to touch art. I like people to be able to pick things up and hold them and investigate them. But I also like other things that are off the beaten path.

One of the artists I work with, Joshua Goode, makes these figures that combine a historical aesthetic with very modern-day subject matter, often through bronze casting. He also makes these mockumentaries of archeological digs, where he finds his own little creatures. It’s very well conceived.

You show several photographers, as well. How do they fit in?

Sometimes, if the work I show doesn’t have a three-dimensional element to it, we create an environment using props so that it does!

Not unlike the projects you did with stylists back in the day. Can you tell us about an environment you created for a show?

Florence Montmare, a Vienna-born, New York– and Stockholm-based artist, made a series of photographs about the ending of her relationship, taken with a four-by-five long-exposure camera. We brought a bed and other furniture into the gallery to represent the rooms she had stayed in.

She invited her ex-boyfriend to come and pose with her for one more picture. She spent twenty-four hours in bed in the gallery waiting for him to show up — or not — and then she took one last photo of the bed alone. It was a great party! And the photographs are beautiful.

You’re located in an extraordinary, historical building in a well-trafficked neighborhood not far from Chelsea’s gallery district. But the building is not obviously home to an art space. How do you get people to come in?

Yes, we’re sort of hiding in plain sight between Ninth Avenue and Hudson Street. It’s hard to find our door, and I’m always trying to explain to people how to locate us. So, we do events. We’ll do receptions and talks, and sometimes, we’ll have artists show how they make their work.

Since artists tend to be friends with other artists, ours all seem to know a lot of performers, and we’ve hosted so many different kinds of performances over the years too — art, opera, dance, string quartets, readings and plays.

The pandemic must really be impacting your program.

We very much relied on doing events, and that obviously does not work right now. So we do virtual shows and virtual events. We’ve had to reschedule some shows for the future.

What can we look forward to this year?

In February, we’re showing work by Ashley Benton, an Atlanta-based sculptor and painter who makes these wonderful ceramic creatures that resemble people with different personalities and animal-like features.

And at some point, we’re going to present sculptures by Ivy Naté. She works with stuffed animals that she collects and then covers in plaster or cement to create these amazing creatures, giving them new life. It will be a sensory experience. She’s using light and sand. You’ll take your shoes off and walk in the sand and sit down and be quiet there in the space. It will feel so good to be back in a gallery experiencing something in person.