January 3, 2021As a 13-year-old junior high school student in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, Jake Szymanski announced his intention to move to New York. “I’d never been to New York. It just seemed like the place for me,” he recalls in a phone call from his home in the South Bronx.

He wasn’t sure how he’d get to the Big Apple, or what he’d do once he arrived. But about a decade after making the pronouncement, he transferred from a local community college to the interior design program at New York’s Fashion Institute of Technology, where, he says, “I learned some serious technical skills.”

In Szymanski’s third year at FIT, designer and entrepreneur Brad Ford spoke to the school’s Interior Design Club, of which Szymanski was president. The two stayed in touch, and in 2016 Ford showed Szymanski’s horsehair-trimmed steel chair at his annual Field and Supply fair in New York’s Hudson Valley. The horsehair, Szymanski says, was “totally untamed. It was a humid day, and the humidity made the hair just explode. It was a wild beast of a piece that attracted a lot of attention.”

Not long afterward, Ford connected Szymanski with people who could help him build his business. “Jake has always impressed me, both with his determination and his talent,” says Ford, who adds that Szymanski’s furniture is “really solid and well executed.”

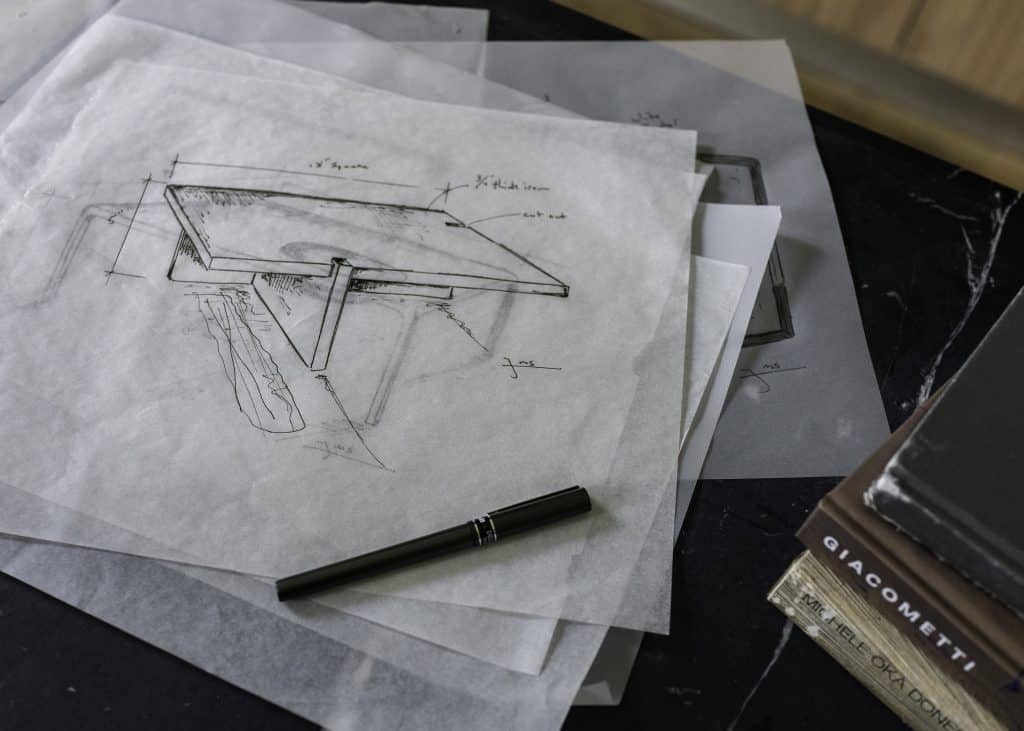

Szymanski got a job at Studio Sofield using CAD software to translate designer Bill Sofield’s hand sketches of furniture into shop drawings. That served as a tutorial in how furniture is made, but he learned far bigger lessons from Sofield, whom he describes as a “genius” — and the kind of person he had hoped to meet q when he dreamed of coming to New York. Sofield, he says, taught him “what it means to have the confidence to follow your own aesthetic, to carve out your own language.”

We `Szymanski’s language seems to reflect such disparate influences as the Flintstones, the Marquis de Sade, Isamu Noguchi and the sculptors Diego and Alberto Giacometti. The brothers worked in bronze, and at first Symanski felt like “I wasn’t legitimate unless I also worked in bronze.”

Over time, however, he realized that he prefers iron, a humble material he sculpts into slightly odd geometries, using grinders and other hand tools. “Tooling marks and surface scratches are part of the pieces’ character,” he alerts customers in advance.

And those marks cannot be painted over. Once the shape of the piece is set, Szymanski says, “we strip it down completely and then apply our own patina, which pulls out blues and purples and creates a finish that, in our case, is quite warm and beautiful and natural.”

Then, as a coup de théâtre, he adds seat coverings made of hair from Mongolian horses. After their annual shearing, the hair is sent to London, where a weaver, working on a small hand loom and mixing in threads of undyed natural English linen, creates a cloth redolent of the past.

“It’s never just one color,” Szymanski says. “It’s a visually deep textile. And the fringe gives it an animal-like quality. It’s almost alive.” Because all the weaving is done by one person, Szymanski produces only a few dozen pieces a year.

Now 32, Szymanski works in a high-ceilinged studio in the Mott Haven section of the Bronx. His two employees — production manager Justin Missner and office manager Gaby Recabar — live just a few blocks away, which has allowed them to coordinate their efforts throughout the pandemic.

Szymanski lives nearby, too. He has filled his rental apartment with his own furniture as well as his metal vessels, which are generally sold in groupings on 1stDibs. Other pieces are by friends and relatives, including his grandfather Charles Diem, who was a serious ceramist on Whidbey Island, in Washington State.

Also represented in the home are works by John Sheppard, best known for his multifaceted lamp bases, and Jake Vinson, of Hotel Fire Ceramics. On the wall behind the Szymanski-designed sofa in the living room is a piece by textile artist Marco Querin. (Szymanski and Querin are collaborating on a new collection of wall art composed of Querin’s weavings fitted into “strategic cutouts” in Szymanski’s metal panels.)

There are found objects as well — among them, a clod of cement with rebar coming out of it (“a construction remnant I found on the ground”) and a shard of terracotta salvaged from a building fire in Chicago. Photos of hands (including one displayed on his kitchen counter among his grandfather’s ceramics) were cut out of a how-to book for palm readers.

A slender white occasional table, made of plaster hand-applied to a steel armature, is part of Szymanski’s line. So is a larger, round table, its honed granite top resting on hydraulically bent steel legs that he says were inspired by 13th- and 14th-century suits of armor in the Metropolitan Museum of Art and by The King, a Netflix movie in which Timothée Chalamet, as Henry V, is seen in Tin Woodman–type armor.

The metal screen in Szymanski’s dining area was his entry in the 2019 Loewe Craft Prize competition. The sculptural piece is so heavy, he says, that “it took five people and a lot of money to get it into my apartment.”

Currently, Szymanski is working on a new line of hammered-metal tabletop pieces, also inspired by armor. His hope is that the work will be imperfect. “My earliest pieces were born of a kind of naivete, and I consider them the most authentic of my designs,” he says.

“With more experience, there’s a temptation to make the work finer and finer and finer,” he adds. “I fight that urge. I’m trying to maintain the soul of these designs.”