September 7, 2015Influential industrial designer Jasper Morrison is often called a minimalist. While he favors simple forms and a limited use of materials, he insists he is most interested in wresting the maximum expression he can from an object (photo by Kento Mori). Top: a collection of utensils he designed for Alessi, 2001. All photos courtesy of Lars Müller Publishers

Pause for a moment, before you read this article, and turn away from your screen until you come across an everyday object that you might otherwise have overlooked. If you’re at your desk, it might be a paper clip or a highlighter; if you happen to be in public, perhaps it’s the umbrella sticking out of someone’s bag.

Even if this item isn’t exactly what Jasper Morrison describes as “recognizable as the most normal example of a particular type of object,” you are looking at something the renowned industrial designer calls “Super Normal.” Along with fellow designer Naoto Fukasawa, Morrison coined the term in 2005 to describe those commonplace, largely anonymous objects that typically go unnoticed, yet abide as too useful to be considered banal.

Originally presented as a 2006 exhibition at Axis Gallery in Tokyo, “Super Normal” lives on as an exhibition catalog, which is spotlighted in Morrison’s latest monograph, A Book of Things (Lars Müller Publishers). The title says everything and nothing at once, a winkingly tautological twist on the notion of “unauthored” design that remains Morrison’s obsession.

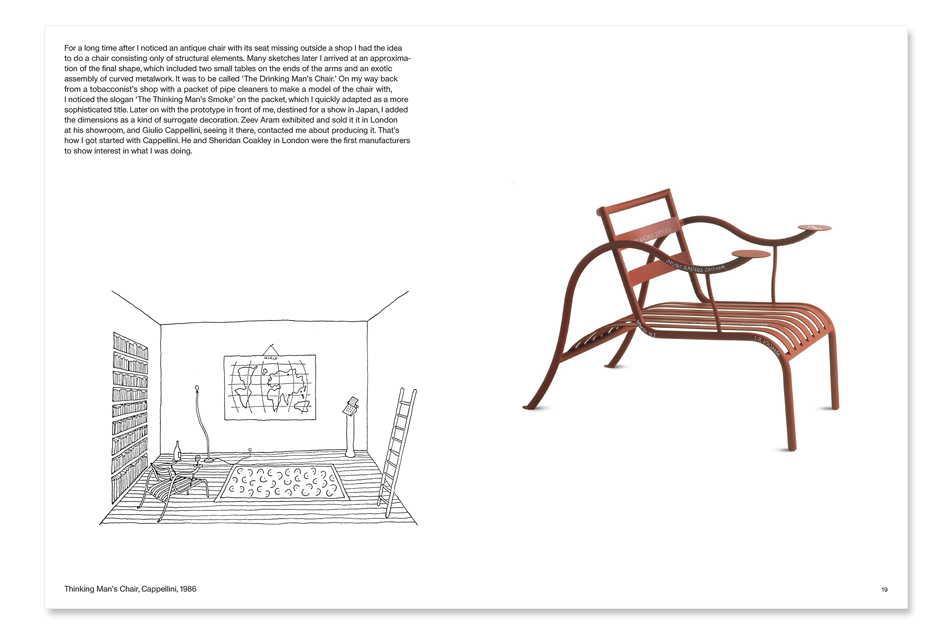

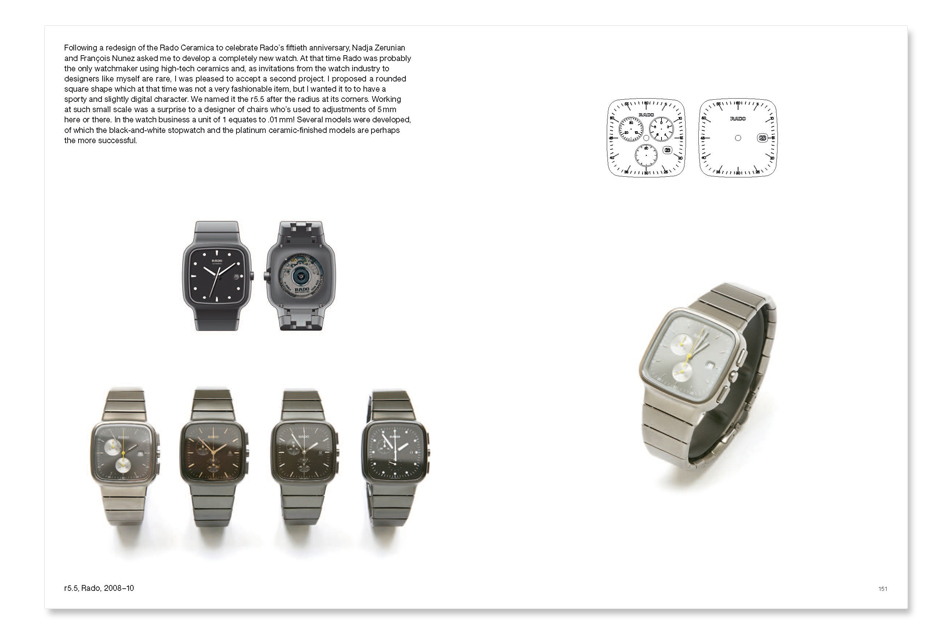

Bound with a handsome woven-textile cover, the new book picks up where a previous monograph, Everything but the Walls, left off. It features nearly 80 projects, most of them from the past eight years with a handful of highlights dating back to the mid-1980s, when Morrison first established his design practice. The majority of pages are devoted to furniture designs, produced by longtime clients such as Cappellini and Vitra; the balance comprise kitchenwares, wristwatches, electronics and a couple of appliances, as well as a few exhibitions and even a viticultural diversion. (Morrison has elected to include his friend’s French vineyard, just south of St-Emilion, where he became involved in winemaking. It is an anomaly among the design objects in the book, but apparently the designer enjoys this avocation. The Australian designer Marc Newson has reportedly joined the venture and there are plans to branch out into making another wine in Greece.)

From cast-iron cookware (for Japanese manufacturer Oigen, 2012) to a Flaminia washbasin (2012) that is essentially an upside-down version of his Smithfield lampshade for Flos (2006), the British designer’s work has long been characterized by a certain understated elegance. The book’s sparse descriptions mostly let the work speak for itself, clearly presenting Morrison’s detail-oriented design process, from concept to execution. Some projects are presented with no expository text, only captions; others take on added significance simply by virtue of multiple photo spreads.

While it is understood that designers do not work in a vacuum — that all design is derivative to a certain degree — Morrison is a rare talent who has such a nuanced understanding of what we now call “user experience” that he has occasionally courted controversy. After moving to a new apartment in Paris, he started using a wine crate as a nightstand — “probably better than anything I could design” — which in turn inspired his Crate nightstand (2006) for Established & Sons.

“They understood the irony where many companies may not have got it, and we reconstructed the crate with a slight upgrade for domestic use (proper joints instead of nails).” The Crate nightstand shocked the design world, Morrison writes, as “many people found it [to be] a cynical abandonment of the designer’s duty to create.”

Therein lies the paradox of Morrison’s practice. By pointing out that objects need not be authored to be useful and long-lasting, he often finds himself looking for ways to improve existing objects. In addition to the dense, discursive interview with Romanelli, the only other text in A Book of Things is a short essay on the Japanese retailer Muji, Morrison’s single most felicitous client and a pioneering purveyor of the “Super Normal.”

He writes: “The Muji concept is to make things as well and as cleverly as possible at a reasonable price, for the thing to be enough in the best sense of the word, and this kind of enough is good for you because it removes status from the product/consumer equation and replaces it with satisfaction, the kind of satisfaction that you have when the money you exchange for the thing is in a good proportion with the value which you receive from the thing, and the thing itself is good at being itself without any pretension of being anything more special.”

A value of a book, of course, is inherently more difficult to quantify than that of, say, a chair, but A Book of Things will more than satisfy any design lover looking to own a thing created by Jasper Morrison.

Bring It Home