August 11, 2019“Jewelry for America,” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, examines the history of jewelry in the United States. William Harper’s 1993 Fabergé’s Twins brooch refers both to Fabergé eggs and the gold objects made by the Ashanti people of West Africa. Top: Detail of a ca. 1905 Dreicer & Co. necklace. All photos courtesy of © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Italy and Greece conjure visions of lustrous gold treasures. India evokes vibrantly colored gems and Mughal extravagance. Japan brings to mind sleek lacquer and delicate floral motifs. Jewelry, like most great design, reflects the history and the culture of the nation in which it was made. But what does the American version look like? The new exhibition “Jewelry for America,” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through April 5, 2020, examines the United States’ jewelry identity, tracing the history of precious little things from the colonial era through the 21st century.

The U.S. has made many homegrown contributions to the design canon, from patchwork quilts and Shaker furniture to the work of icons like Frank Lloyd Wright and Calvin Klein. When it comes to jewelry, however, it’s not so easy to pinpoint a distinctly American look. That may be the reason the topic is seldom explored; except for a small display in 1926, “Jewelry for America” is the Met’s first exhibition dedicated to the subject. The idea for it was born out of another show, last year’s blockbuster “Jewelry: The Body Transformed.”

“Because there was so much ancient and non-Western jewelry, we didn’t really have a chance to show much of the American collection,” says Beth Carver Wees, the Ruth Bigelow Wriston Curator of American Decorative Arts and a co-curator of the American pieces in last year’s exhibition. “I’ve really worked on building up our collection since I started at the Met, 19 years ago, and I thought it would be fun to show the whole history.”

Known as carriage covers, these spherical hinged pieces — used to conceal precious stones during the day, when a lady might be traveling by carriage and vulnerable to robbery — were an innovation of American jewelers in the 1870s. This particular pair is from 1882–85.

The exhibition begins with the country’s first European settlers, who brought with them only those luxury wares they most prized. Whether because of a lack of resources or puritanical mores, the jewelry from this era eschewed extravagance in favor of sentimentality. More than mere objects of adornment, the first American jewels served as tokens of love, mourning, luck or commemoration. A group of brooches dating from the early-to-mid 19th century feature intricately painted miniature portraits of lovers, relatives or children — keepsakes from before the advent of photography. Several pieces reflect the 19th-century vogue for earrings, bracelets or pendants fashioned from a loved one’s hair — a tangible way of keeping friends and family close. The exhibition even includes a page from Self-Instructor in the Art of Hairwork, an 1867 do-it-yourself publication that proves just how hot the trend was.

While these kinds of designs were not exclusive to the United States — without email, phones or reliable postal service, sentimental jewelry was a popular reminder of one’s nearest and dearest in many Western nations — it’s telling that they formed the foundation of the country’s jewelry. “In Europe, royals and the aristocracy wore those more elaborate jewels,” notes Wees. “In America, we didn’t have that class.” Dazzling gems, so strongly associated with the British crown, didn’t quite jibe with America’s vision of a democratic republic.

Artist and designer Daniel Brush created this torque, 2010–14, from aluminum tubing used for airplane refrigeration coils, which he brush engraved and set with tiny multicolored diamonds.

Modesty, however, eventually gave way to glitz. The 1867 discovery of diamond deposits in South Africa made the gems more accessible. Literally striking gold, as well as silver, gave the U.S. the resources to develop its own domestic jewelry industry. Newark, New Jersey, perhaps surprisingly to modern audiences, became the epicenter of the country’s jewelry industry, with some 200 manufacturers, including such firms as Riker Brothers and Unger Brothers, generating around $5 million in annual revenue by the 1870s. “Though it sounds a little corny, [that era] was really about American ingenuity — coming into our own, inventing our own styles and certainly creating our own industry,” says Wees.

The show contains several examples of original, uniquely American creations. A circa 1851 hair comb, for example, is made of vulcanite, a chemically treated rubber invented by Charles Goodyear that affordably mimicked the look of more expensive materials like tortoiseshell and jet. Then there are the carriage covers — hinged gold orbs that could snap on and off of diamond earrings to conceal the precious stones during the day, when a lady might be traveling by carriage and vulnerable to robbery — which were a pragmatic design solution patented by American jewelers in the 1870s. Both designs display the innovative, unconventional attitude that would come to define the American approach.

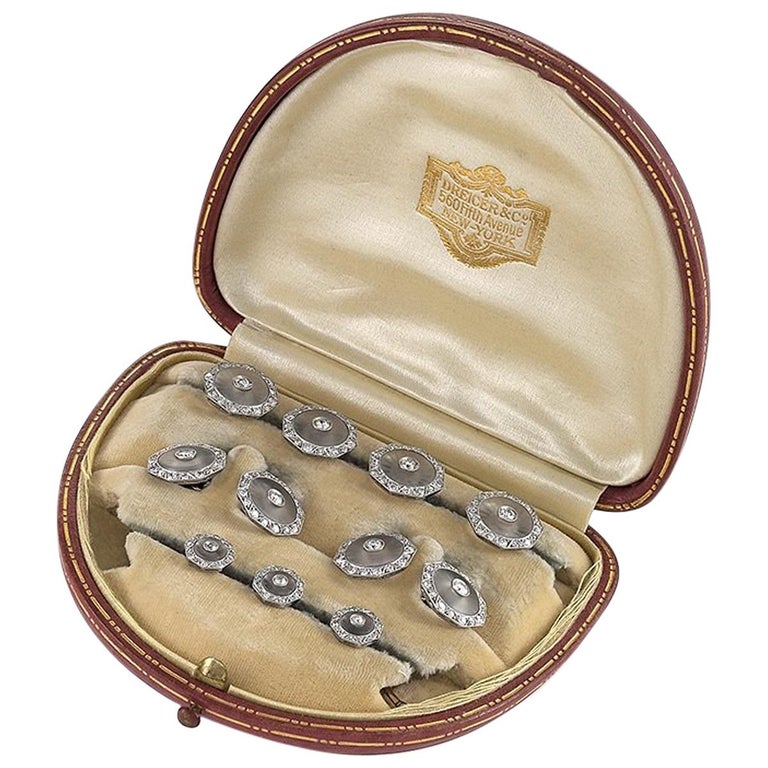

Tiffany & Co., founded by Charles Lewis Tiffany and John B. Young in 1837, looms large in the exhibit, from early designs showcasing native materials like Montana sapphires and Mississippi freshwater pearls to exquisitely rendered riffs on French Art Nouveau by Charles Lewis Tiffany’s son Louis Comfort Tiffany. But numerous lesser-known makers illustrate the diversity in U.S. jewelry design. Dreicer & Co., a leading New York firm at the turn of the last century, was founded by Russian immigrants and catered to such well-heeled clients as Sarah Bernhardt and Caroline Schermerhorn Astor. Pioneering female Arts and Crafts designers Eda Lord Dixon, Marie Zimmermann and Florence Koehler produced some of the finest works of the American Arts and Crafts movement. A group of Zuni turquoise, coral and shell necklaces represents the rich tradition of Native American jewelry — the country’s one truly indigenous style.

In this 1878 Tiffany & Co. mourning brooch, plaited hair is set in a gold mount bordered by natural pearls and black enamel rays.

As the show moves deeper into the 20th century, America’s penchant for bold design comes into focus. Iconic styles that spurred international trends, like Fulco di Verdura’s 1930s gemstone-studded Maltese cuffs, which were reproduced by his friend Kenneth Jay Lane in 1977, and David Webb’s enameled zebra cuff, designed in 1963, mingle with the avant-garde works of mid-century modernists Art Smith, Sam Kramer and Alexander Calder. The contemporary pieces included, by the likes of Daniel Brush and Thomas Gentille, illustrate how U.S. designers have embraced non-precious materials, from aluminum and Bakelite to eggshells and electrical wire.

Unbound by tradition, the United States gave designers the freedom to experiment, to be irreverent. It’s interesting to see costume jewelry, like a pair of Kenneth Jay Lane cuffs from the collection of Lauren Bacall, in this context. But really, what’s more American than perfecting a democratic “look for less”? That Lane’s designs in humble metal and glass were worn by such boldface collectors as Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis and the Duchess of Windsor just goes to show that Americans aren’t afraid to have fun with their jewelry.