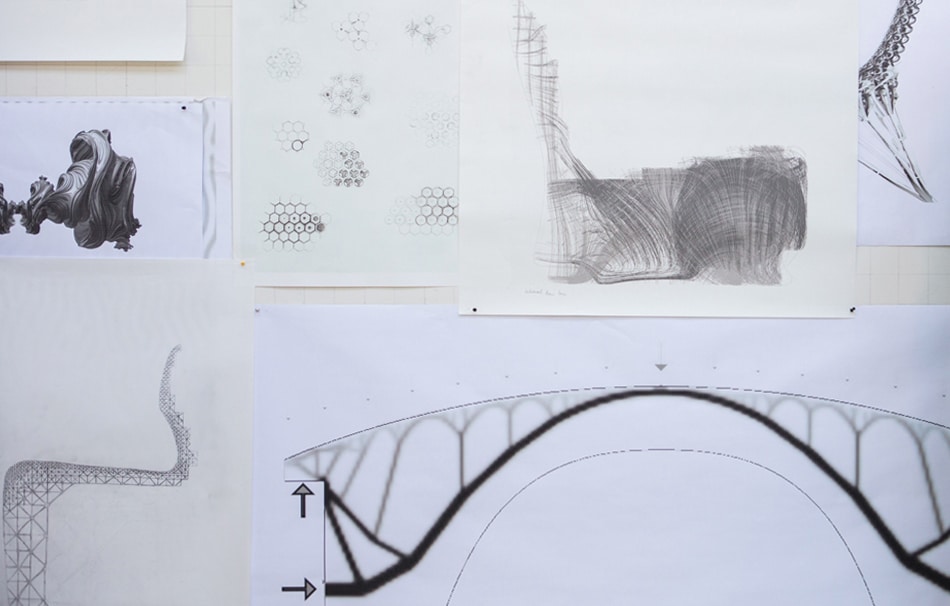

October 2, 2017The subject of a new show at New York’s Cooper Hewitt museum, Dutch industrial designer Joris Laarman uses the most cutting-edge of technologies to create works that continue the traditions of the oldest forms of artisanship. Top: Laarman’s lab has developed a scheme for a pedestrian bridge entirely built by 3-D-printing robots that will be installed over Amsterdam’s Oudezijds Achterburgwal canal next year. Both photos courtesy of Joris Laarman Lab

We tell stories about the future,” says Dutch designer Joris Laarman, summing up the work of his studio-cum-laboratory, which he founded in 2004 with his wife, filmmaker Anita Star. The “we” he speaks of also includes some 40 engineers, programmers and craftspeople, along with a growing team of robots.

Many of their greatest achievements — a now-iconic chair formed according to the principles of bone growth, a rococo swirl of a radiator, the world’s first functional 3-D-printed steel bridge, to name just a few — are the subject of an exhibition on view through January 15, 2018, at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, in New York. The publishing house August Editions will release an accompanying volume, Joris Laarman Lab, next month.

Equally enamored with functionality and ornament, efficiency and playfulness, the robot and the artist, Laarman uses algorithms to create what he describes as “beautiful objects that make sense.” But technology is just one part of his fearlessly forward-looking stories.

“Joris works with three-D printing and programmable materials while showing how craft is really important to bringing these things into our world,” says Cooper Hewitt assistant curator Andrea Lipps, who oversaw the exhibition’s New York presentation (it originated at Amsterdam’s Groninger Museum and will travel next year to the High Museum, in Atlanta, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston).

Among the pieces that rocketed Laarman to fame is the Bone chair, 2006, which his studio developed by creating a program that mimicked the growth, density and forms of a skeleton’s structure. “He used the algorithm as the form giver, but then the form had to be wrestled out of the computer,” says Andrea Lipps, the curator of the Cooper Hewitt show. Photo courtesy of Joris Laarman Lab

Lipps points to Laarman’s 2006 Bone chair, which mimics how bones cleverly shift density: Material is generated where strength is needed and removed where it is not. Rendered in mirror-polished aluminum, the primordial form is at once suggestive (tibia? fibula? vertebra? rib?), ingenious and elegant.

“He used the algorithm as the form giver, but then the form had to be wrestled out of the computer,” she says. “It required a level of skill and craftsmanship and dedication to create this exquisitely beautiful object.”

Beyond the rigor and innovation of Laarman’s practice, Marc Benda, of New York’s Friedman Benda gallery, singles out “the way he extracts beauty from very mundane and very complex explorations that, without his interventions, wouldn’t have any place in product design.”

Examples range from stunning tables designed to resemble flocks of starlings or flat-topped cumulus clouds (both developed using 3-D animation software) to Half Life, a table lamp powered by genetically modified bioluminescent cells that glow in the dark under the right conditions. Developed in collaboration with scientists at the University of Twente, in the Netherlands, the lamp proved tricky to exhibit because of import restrictions on the organisms involved, but Benda highlights the “beautiful thought process” it represents.

Now spread across two sites — one a former textile factory, the other an erstwhile shipyard — on Amsterdam’s gritty outskirts, Joris Laarman Lab is able to spin ever more intricate tales. The designer recently made time to discuss with 1stdibs his career, the exhibition and his latest projects.

You burst onto the international design scene in 2003 with the Heatwave radiator — part of your thesis project at the Design Academy Eindhoven — and almost immediately began working with some of the world’s leading furniture companies. It’s rare to get that kind of experience so early in one’s career. How did it affect you and your decisions about what to do next?

In the beginning of anyone’s career, you’re just figuring out what you want to do, and after my graduation project, I was shot into this design world that I really didn’t know too well. I got in contact with all these big design brands, like Vitra and Flos, and it was a very educational couple of years for me.

I worked on a couple of projects with these brands and found that my passion really lies in the experimental side of the design world — figuring out new manufacturing processes and new materials, making new form languages and manufacturing tools and everything that has to do with the future.

Your Bone chair and the Bone furniture series that followed have reshaped our definition of design in the 21st century. Why do you think they have proved so influential?

This work shows what is possible in the digital age. Now, nature can be more than a stylistic reference. We can use natural principles to generate shapes, like an evolutionary process. Also, this way of designing is an interaction between man and computer. I never could have come up with the design of the Bone chair myself. Mine would probably have looked much more artificial.

You use a broad range of cutting-edge manufacturing techniques and also push those methods forward. How do you become aware of new processes and technologies?

It’s quite different for my generation of artists and designers compared with the generation before us. The Internet opened up a whole new world of information, and everything and everyone became much more accessible. I’ve always been interested in science and engineering, so I just got in contact with people in those fields and then built up a network. Sometimes, we develop or think of an idea, and other times, we’re approached by people to work with them on a specific project.

How do you spend your working time?

We have two companies. One is my own production company, which makes all the design works and develops the experimental stuff. And then, I founded MX3D, a robotic printing company. It prints steel, bronze, aluminum and other weldable metals. The metal printing is taking up a lot of time and energy, because it’s a new technology that’s extremely promising and I want to explore it before everyone else does.

A member of Laarman’s studio works on a Hexagon Makerchair, 2014, assembling its various milled-walnut pieces. Photo © Robert Roozenbeek

How would you describe your work at MX3D?

You could compare our process to how architects and designers and artists in the early modern period worked. When industrialization happened, people were looking to form languages that were limited by industrial machines — mostly geometric shapes and primary colors, for example. Now, we see that these digital manufacturing tools allow new forms, new materials, new colors, new everything! It’s much less geometric and much more organic, with gradients and things divided into little cells. It comes back to codes behind objects that you find in nature.

One of the most exciting projects of MX3D is the 3-D-printed bridge you’re making for the city of Amsterdam. How did this come about?

It started more than two years ago with a concept: With this technology, we wanted to see if we could do something really big and functional as sort of a poster project for what is possible — to create something five steps ahead of what people would think is possible. We are located in Amsterdam, and it’s a city full of canals and water, so a bridge seemed very logical. It’s a whole different engineering and scope compared with what we are used to, because it has to be functional. People will actually walk on this bridge.

Holland has a long welding history, so there are some nice historic links to what we are doing. Every Friday, we’re open to the public, so people can observe the process.

That seems to be at the foundation of all of your work — showing the process.

In my personal work, I like to show how stuff is made. I think an object is most exciting when you see somebody’s struggle in doing something new. One of my idols from the last century is Gerrit Rietveld, who created these objects that were supposed to be industrially made, but if you look at them closely, you see that they’re all hand-hammered into a certain shape that looks industrial, but that was not yet possible.

We are also pushing the envelope, and you see that. You can see the whole experimentation process. In one hundred or two hundred years from now, that will be much more exciting to see than something that is perfectly finished or entirely robotically made.

Is this something you thought about with the Cooper Hewitt exhibition as well? Are visitors able to readily comprehend how the works they’re seeing were made?

We added a lot of video material to the exhibition for exactly this reason. Anita, my partner, wife and the mother of my kids — we do everything together — has a film background. We usually use video to document the manufacturing process and the whole concept behind things. In the exhibition, with every work, you can see a video explaining where it comes from.

In addition to objects hot off the metal printer, the exhibition includes the new time-line project you’re working on. Is it like a grand unified theory of the world?

It’s hard to explain, but it’s a time line that I use as context for my work. It starts with the Big Bang and goes way into the future and links all kinds of data streams, from Moore’s Law to carbon dioxide to the average lifespan to your own personal happiness. It’s all within layers of this time line, so if you click on certain layers you see overlaps. I can look back to when I made a specific work, like five years ago, and see what happened in the world during that time and why I did that — and what’s important to work on in the future.

Laarman’s Ivy pieces, 2003, can be used to create a climbing wall, putting an ornamental twist on fitness and a whimsical spin on wall decor. Photo courtesy of Joris Laarman Lab

Your work is like an ongoing conversation between craft and technology. Is beauty something you think much about?

Beauty is very important to me. It’s quite a philosophical thing. As robots and artificial intelligence become more and more influential, I wonder what is still valuable?

It’s very important that people still communicate with other people about the things they are making. Even with an object that is digitally manufactured or made by robots, in the end, you see that it’s a concept that comes from a human, not from some computer. And you see that it’s made by people, in collaboration with robots.

Are robots good collaborators?

Our company is like a mini-society of the future, you could say. We have a mix of industrial engineers and people who know everything about robots, but also craftsmen who are trained as blacksmiths and carpenters. That combination of those types of people and machines and how they learn from each other is really nice. I hope it’s what the future will be like. Maybe that’s a bit naive, but I like it.