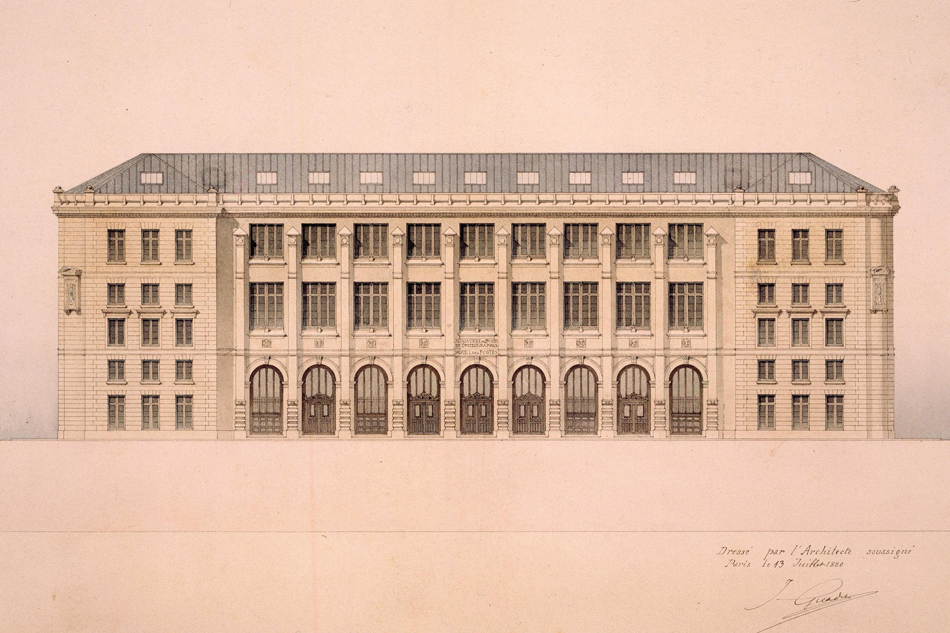

April 17, 2013The subject of a multifaceted new show at MoMA, the 19th-century French architect Henri Labrouste made his name with two Parisian libraries, including the Bibliothèque Nationale (1875), whose reading room soars and shimmers. Photo by Georges Fessy; Top: Labrouste’s rendering of the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève shows the bright white vaults he designed to reflect light from the building’s huge windows.

The exhibition “Henri Labrouste: Structure Brought to Light,” Now at New York’s Museum of Modern Art until June 24, is one of those curatorial passion projects that only seem to happen when an influential museum insider shepherds them along with great care.

Barry Bergdoll, MoMA’s chief architecture and design curator, is one such insider. He fell in love with the work of Labrouste in college, and now, alongside a team of French curators, Bergdoll has organized an exhibition to illuminate the work of the man he calls “one of the great form-givers of the 19th century.” Not that Labrouste’s name trips easily off many tongues. “He’s very well-known to anyone who’s had architectural training, and almost completely unknown to others,” says Bergdoll. “We are going to try and change that.”

Labrouste, a native Parisian who studied at the all-powerful École des Beaux Arts, is primarily known for two landmark libraries in his hometown, the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève (completed in 1850) and the Bibliothèque National de France (completed in 1875) — both of which, amazingly, are still in use today. “They are two of the great rooms of Paris, but most Parisians have never been in them,” says Bergdoll. Both require special access.

Recently Bergdoll spoke with Introspective’s Ted Loos about the evolution of information technology, Labrouste’s pioneering approach to “total immersive environments” and echoes of the architect’s work that still resonate today.

The MoMA exhibition uses a mix of models, renderings and photographs to capture Labrouste’s ethos. Photo by Jonathan Muzikar

A lot of people think Van Gogh’s Starry Night, from 1889, is the oldest thing in MoMA. How is this show MoMA-appropriate?

First of all, the MoMA photography collection starts with the invention of photography in 1839. So we’re completely contemporary with that. And Labrouste’s Sainte Genevieve library is actually one of the earliest buildings to be photographed.

Labrouste is an architect who launched his whole project with the term “avant-garde,” with the new role of the architect as a social leader. It’s actually an early-19th-century term and comes out of European Romanticism. I like to make the point that “avant-garde” was taken over as an artistic term exactly at the moment when it no longer was a functioning military term.

How did you organize the show? I see that his studies of Greek ruins are at the beginning.

The first corridor is laid out like a 19th-century salon, with an exhibition of drawings from his early years. It’s actually about his voyage of discovery. Labrouste asks the question, “If our era is also changing so radically, what kind of architecture do we need to make?”

How was he thinking about information technology?

Labrouste’s are among the very first public libraries ever designed, but he’s thinking about all sorts of issues that relate to the BlackBerry Age: One, how do I get information; and two, how do I get that information privately and then study, respond or communicate when I’m surrounded by other people?

While grand in scale, Labrouste’s spaces often feel intimate, even his reading room at the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève. Photo by Michel Nguyen

Sainte-Genevieve, the first library, has such a soaring interior.

You have a sense of this very luminous, lofty space. It creates this incredible, monumental, impressive area above your head. But actually the whole thing is very functional — it’s an enormous light reflector.

The barrel vaults?

The barrel vaults are white, with these big windows on all sides. This was the first library ever open at night because it was installed with gas lighting, which was brand new in that period. The show includes a digital simulation of what it’s like to be in the building as night falls.

In the age of Wikipedia and the Internet, what relevance do bricks-and-mortar libraries still have?

Well, there must be some, because there are so many that have been built in the last 20 years. Think of Rem Koolhaas’s Seattle Public Library: It’s a public building and people are going there because they need something — many don’t have access to a computer, for example. It’s fascinating that the museum and the library, the two great 19th-century building types, are again very present in the 21st century. With Google Art, you could also ask, Why bother going to a museum?

At the Bibliothèque Nationale, Labrouste’s impossibly thin columns support a series of delicate domes. Photo by Georges Fessy

What’s the big difference between the two libraries?

You can really see the evolution of a great architectural mind. The Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève is a study or display library and the collection is highly visible. The lion’s share of the collection is literally present in the room.

The Bibliothèque Nationale is a deposit library, like the Library of Congress in the U.S. Under French law, one copy of everything printed in France must be deposited at the Bibliothèque Nationale. That goes for books, periodicals, prints, advertisements . . . So there’s a separation between the reading room, which is surrounded by reference works, and the rest of the collection, which is kept in these very innovative metal stacks. The stacks are connected visually, through an extraordinary arch but also through a system of pneumatic tubes.

Labrouste is famous for his use of iron — how so?

He is usually celebrated for the structural innovations of iron. He’s not the first to work in cast iron — that was used in market halls and train stations. But he was the first person to suggest that it could be used in a noble way, to express a great public function.

Both libraries use it?

They both are made of an iron framework that’s set into a masonry envelope. So the two materials are simultaneously independent of one another and quite codependent. They would both need to be thicker if they weren’t working together. The iron is not self-supporting.

And the lovely decoration relates to the function?

The filigrees relate to the structural principles of a truss or an arch. He was also the first person to really explore, for instance, in the Bibliothèque Nationale, the types of thin ceramics that make these domes into light reflectors. These buildings are so innovative in lighting design.

Although he worked in a decided modern idiom, as in the vault structure of the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, Labrouste’s studies of classical ornament (a capital from the Pantheon, say) greatly influenced the ornament he incorporated into his designs.

I see the decorative motifs changing as the 19th century progresses to a more Romanesque look.

Yes. In the past, Labrouste has never been celebrated for his ornament, because everybody wanted him to be so modern — they kind of wanted to not see the ornament. Now, everyone’s designing ornament and pattern.

What was his domestic architecture like?

Actually, surprisingly traditional, neo-Renaissance. We chose not to show any of it, since the show isn’t a portrait of his whole career. We were more interested in those works that were terribly influential.

Do we see his influence in, say, train stations? Like the famous Gare d’Orsay, which is now the Musee d’Orsay.

Orsay, from 1900, would, in some people’s view, almost be a step backwards from Labrouste, because it uses vaults in a very heavy way, to give the weight and nobility of Roman architecture. Labrouste, in contrast, was very taken with the lightweight aspect of Gothic structure, even though he never did a Gothic building.

How does the MoMA show address the post-Labrouste era?

For the third section of the show, we wanted to ask, How do you define influence, and where does it stop? Of course there are his students, and there are places like the Boston Public Library that take a direct quote from him. In the exhibition, we’ve done this little cute trick: Instead of having a card catalog, we’ve replaced that with an interactive digital kiosk. We wanted to show that the cross-reference on a library card is the origin of a hyperlink. We also connect Labrouste to, among other things, Norman Foster’s Stansted Airport. It’s related through this theory of the large public hall of assembly but also in its expression of structure.

Botanical paintings inside the arches of the Bibliothèque Nationale’s reading room reflect the shapes of the space’s soaringly high windows. Photo by Georges Fessy

The catalog makes a point of saying he was a shy and melancholic character.

I think he was a reluctant revolutionary and a very austere person. But at the same time he was a very generous teacher, which is why his students loved him so much and followed him in his radicalness.

When did you discover him personally?

I was an undergraduate when the 1975 show “The Architecture of L’École des Beaux Arts” happened at MoMA.

Did you make a pilgrimage to the libraries?

Oh yeah, the minute I got to Paris. One of the things that’s so extraordinary is that in photographs they appear incredibly monumental, but they’re also quite intimate as spaces. The New York Public Library is a much more overwhelming building.

Were they good spaces for studying and contemplation?

Yes. Because I was a doctoral student in the 1980s in Paris, I spent weeks on end in the Bibliothèque Nationale. It’s fantastic, actually. You went away for an hour at lunch, and you looked forward to being back in that space.