September 3, 2023“It must be the longest house in the southern hemisphere,” London-based art conservator Suzanne Press says with a laugh. “It extends from one side of a mountain to the other.”

She’s describing Coromandel House, the dwelling her parents, Sydney and Victoria Press — he, a South African farmer’s son turned retail magnate, and she, an American-born former fashion designer — built in the early 1970s on their 14,000-acre agricultural estate in Mpumalanga province, three hours north of Johannesburg. Decades ahead of its time in its eco-sensitivity, it resembles an ancient stone ruin.

The architect was Marco Zanuso, a titan of postwar Italian design. And now, he and this little-known residence are the subjects of a fascinating book, Creating Coromandel: Marco Zanuso in South Africa (Artifice), coauthored by architects Edna Peres and Andrea Zamboni. Press herself spearheaded the project, which documents the making of the house and its seminal role in the development of a relativist regional approach to architecture in South Africa.

Throughout much of the world, Zanuso is best known as a furniture designer. His elegantly plump Lady chair frequently stars in stylish interiors outfitted with vintage Italian design. Yet few are familiar with Zanuso’s career or the significance of that armchair. When he launched the Lady chair, in partnership with Arflex in 1951, he sparked the modernization of Italy’s still-artisanal furniture industry by manufacturing the design in pieces and making its cushions out of polyurethane foam, a recently developed industrial material. A decade later, he and adventurous compatriots like Mario Bellini, Joe Colombo and Ettore Sottsass reinvented the domestic landscape by designing daringly different furnishings and accessories for a new, more freewheeling lifestyle.

According to Paul Donzella, a New York dealer in mid-century Italian design, because Zanuso concentrated his prodigious talents on mass-manufactured designs, we’re unlikely to see headlines about a rare or custom piece of his bringing an astounding price at auction, as works by Gio Ponti and Carlo Mollino, an earlier generation of Italian design giants, have. Still, his significance is uncontestable. “The Lady chair is probably one of the twenty most iconic twentieth-century pieces,” Donzella says. “But my favorite of his designs is the Regent chair, from 1959. I always grab those chairs whenever I can. I have one in my own home.”

“Zanuso always placed function on the same level as form,” observes Daniele Lorenzon, of the Milan-based design gallery Compasso. “His pieces come with a soul, a recognizable character with a specific name.” Lorenzon likens Zanuso to the formative mid-century American designers Charles and Ray Eames and George Nelson in that he “had the same transversal and multidisciplinary design approach and long and fruitful relations with mass-production brands.”

As a practicing architect, Zanuso focused on office and industrial projects. However, he designed a pair of striking if rustic stone vacation houses for his family on the rocky coast of Sardinia evocative of the megalithic edifices that dot the island. Photos of the houses in a magazine caught the eye of Press’s mother. Enamored by their elemental poetry, Press’s parents invited Zanuso to visit their South African farm and design a retreat for them and their seven children that would similarly harmonize with its surroundings. He eagerly complied, and so began an extraordinary collaboration between three creative visionaries.

Press, the second youngest in the family and around seven at the time, remembers Zanuso as “an immaculately dressed Italian who was a happy, open guy and often went horseback riding with us children.” He was captivated by the wild beauty of the highveld, its pristine spruce forests and the remnants on the property of precolonial stone enclosures built by the Koni, the area’s original inhabitants. After spending time with the family and carefully studying the terrain and climate, Zanuso conceived an innovative house equipped with many advanced technological features while also deeply informed by bioclimatic principles in use in the Mediterranean since ancient times.

The structure was indeed long, stretching 525 feet. It was also narrow, with thick concrete walls flanked by a row of buttresses, and clad entirely in local dolerite, with a green roof of indigenous plants. Zanuso situated it on a steep slope, high enough to escape the frequent mists but protected from the wind, with stunning views of the valley and a far-off mountain waterfall.

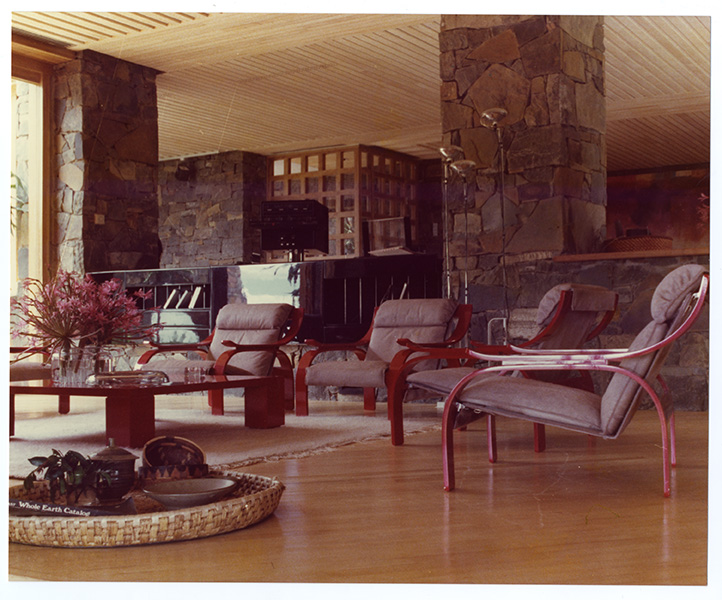

The layout was equally experimental. At its center was an expansive living area with two narrow wings extending from each side. These housed bathrooms and sleeping areas, some private, others open plan. Inserted between them and visible from the communal core were two courtyards, one planted with native vegetation, the other featuring a fish pond and a swimming pool. Providing shelter from sun and wind, the courtyards created a microclimate for the house while also affording an intimate connection to the wilderness beyond.

To further protect the interior from the sun’s heat and glare, Zanuso designed exterior shutters and windows recessed within the walls — a favorite of Press’s. “I used to love to curl up with a book in those deep window sills,” she recalls. “And all the plants outside had been collected by my mother and a botanist on trips into the countryside with us children as her excited companions.”

Press’s family idyll at Coromandel House was sadly brief. By the end of the 1970s, her parents’ marriage had collapsed, and she, her mother and all but one of the other children left South Africa to make lives in England and the U.S. After Press’s father died, in 1997, the house was sold to the agricultural collaborative that worked the estate, and most of the furnishings — by Zanuso and a host of other modern European designers, along with the fashionable Californian John McGuire — were haphazardly dispersed.

Curiously, interest in Coromandel has surged in recent years. “Although the house suffered some decay, forward-looking South African architects have been journeying to see it,” says Peres. “Their admiration has only intensified as the overgrown plantings have blurred the lines between building and nature.”

Press hopes Creating Coromandel will further amplify interest in Zanuso’s South African masterwork. Currently, efforts are underway to gently restore the house and take it completely off grid, with the intention of converting the romantic ruin into a six-suite eco-getaway for architecture aficionados.

That Zanuso is responsible for such a compelling and pioneering work of green architecture is no surprise to Patrizio Chiarparini, of Duplex, a design boutique in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn. “There was a utopian aspect to all the activity of his production,” says Chiarparini, who especially admires Zanuso’s groundbreaking 1966 Lombrico modular sofa for B&B Italia, which he believes inspired de Sede’s cult-classic DS-600 curving sectional. “What concerned him was elevating life. Zanuso’s designs were like the times — very rock and roll.”