July 31, 2022The state of Maine has issued a siren call to American artists for more than two hundred years. Some are drawn to Maine’s personality, its ruggedness (it has long, cold winters), its cussed independence (it seceded from the state of Massachusetts) and its sheer remoteness.

“Maine has fed the imagination of the world,” says Anne Collins Goodyear, codirector with her husband, Frank Goodyear, of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, in Brunswick. To illustrate the state’s influence on the wider art world, the Goodyears have organized “At First Light: Two Centuries of Artists in Maine,” a revelatory exhibition of more than 100 works, including colonial portraits, folk art, pottery, landscapes, paintings, photographs and Native American basketry.

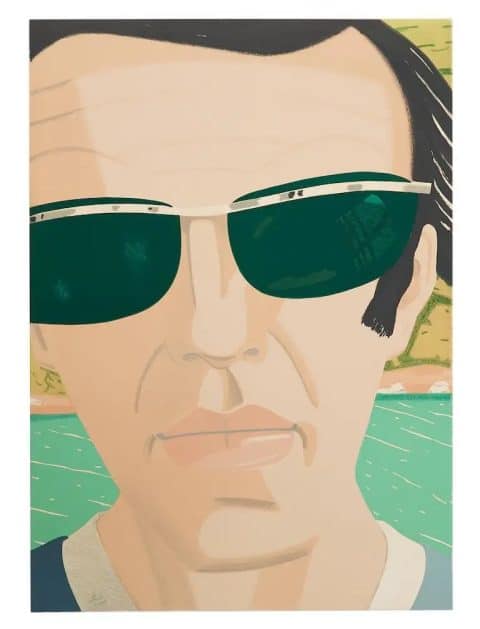

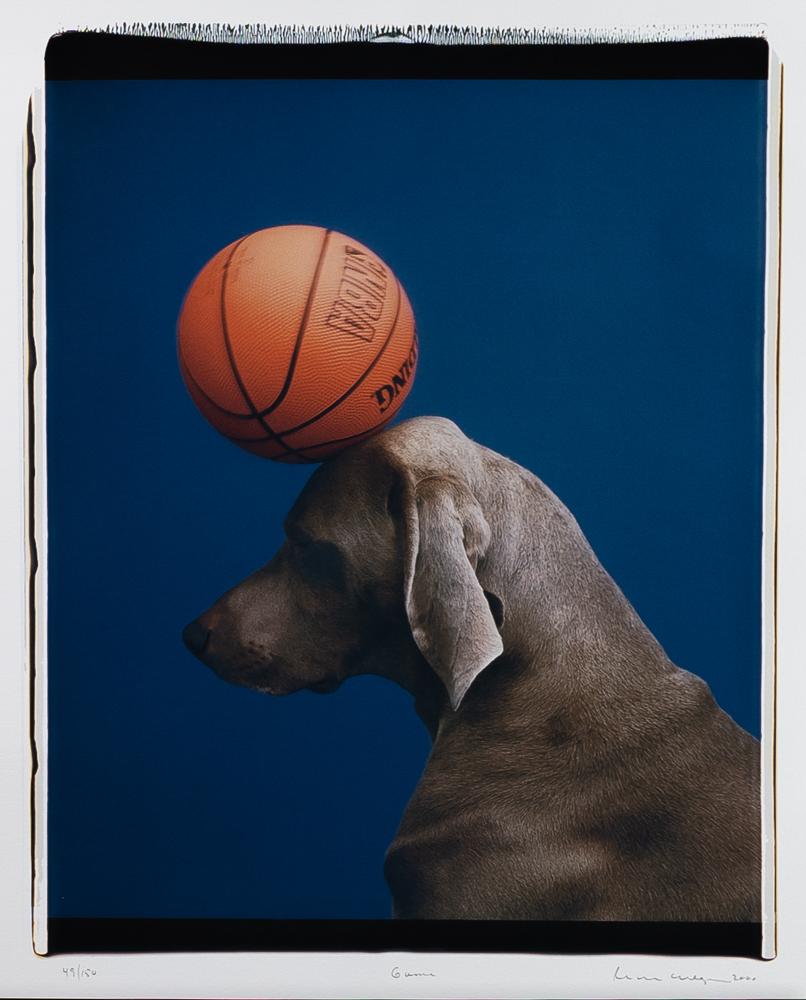

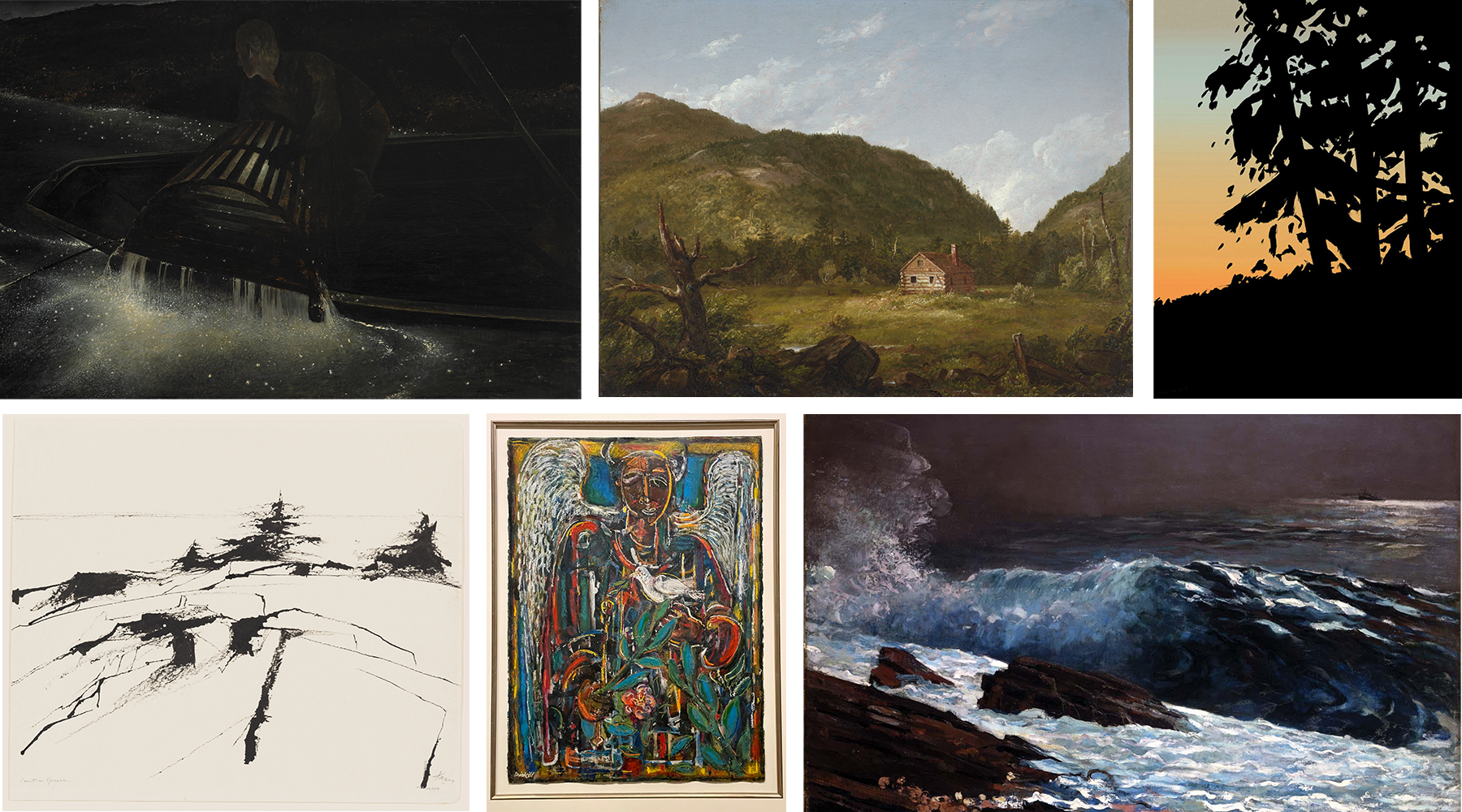

Up through November 6, it features the well-known artists who have shaped how we see Maine: Winslow Homer, Andrew Wyeth, John Marin, Fairfield Porter, Robert Indiana and Berenice Abbott, as well as living legends like Alex Katz, Richard Tuttle and William Wegman.

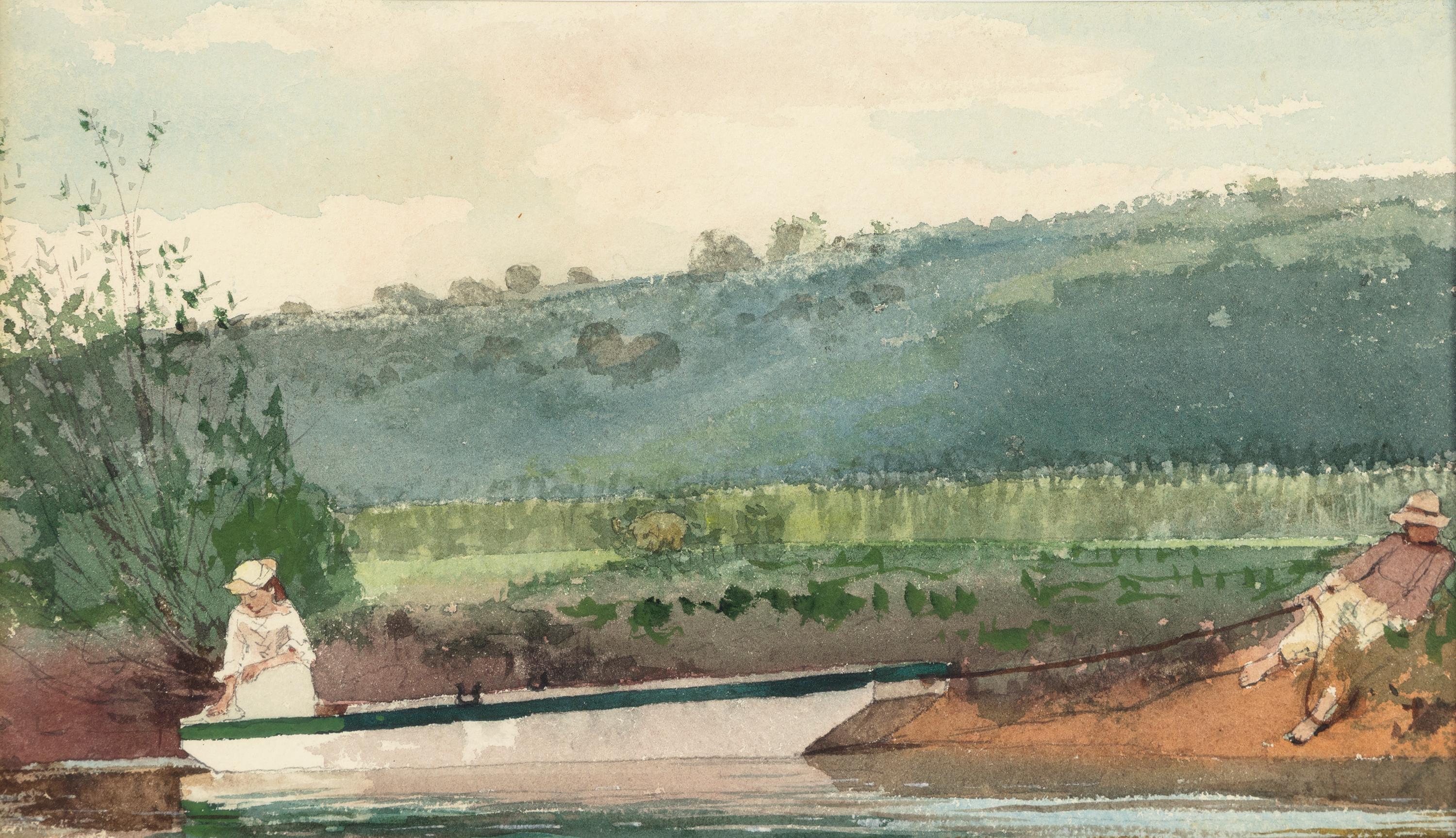

The show boasts such beloved favorites as N.C. Wyeth’s 1939 oil Island Funeral, depicting a flotilla of mourners sailing to an island off Port Clyde; Thomas Cole’s 1844–45 oil House, Mount Desert, Maine; Homer’s 1890 oil Sunlight on the Coast; and Eliot Porter’s ravishing 1942 dye transfer print Apples, Great Spruce Head Island, Maine.

The Goodyears conceived “At First Light” in 2015 to commemorate Maine’s bicentennial on March 15, 2020. Instead, on that very day, the state shut down due to COVID, and the exhibition never opened — which gave them more time.

“In the intervening two years, the world changed so much we thought it was necessary to look deeper,” Anne Goodyear notes. “We asked ourselves, ‘What is Maine’s elusive secret sauce?’ ”

They were able to make their roster of artists far more diverse. Reuben Tam, for example, is a Hawaiian who settled in Maine. Lynn Mapp Drexler was a Black abstract painter from Virginia who studied with Robert Motherwell and moved to Monhegan Island permanently in her early 40s. David Driskell was a Black painter and curator from Georgia who came to love Maine while attending the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture.

Ten years ago, before the Goodyears began organizing their show, Michael Komanecky, then curator of the Farnsworth Art Museum, in Rockland, proposed an idea to his friend Walter Smalling Jr., a renowned architectural photographer who lives in Maine.

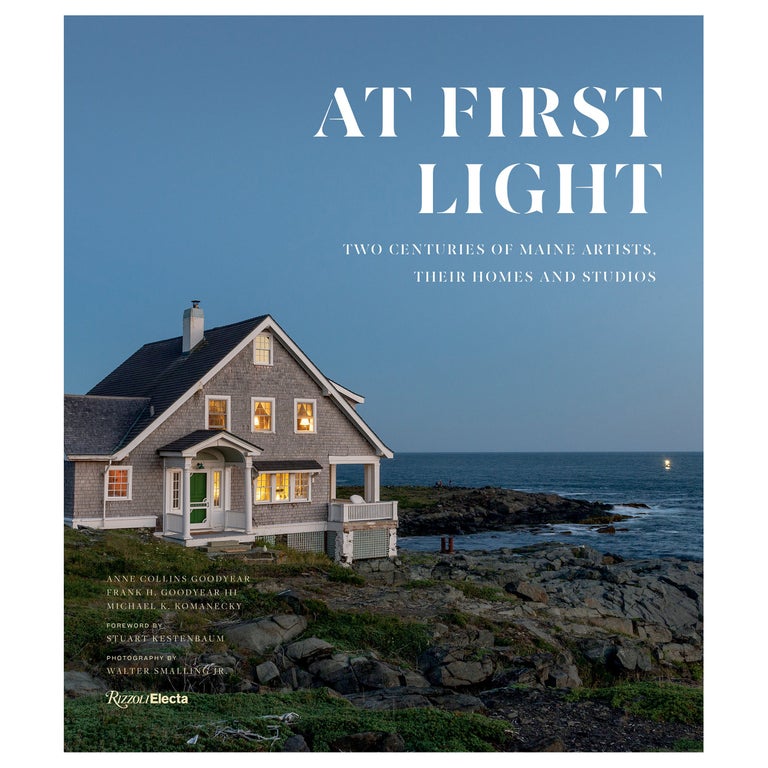

“The Farnsworth’s mission is to celebrate Maine’s role in American art,” Komanecky recalls telling Smalling. “How about doing a book for the bicentennial on artists who work in Maine?” Smalling at once embraced the idea and eventually spoke to the Goodyears, who proposed staging a tandem show: Along with their exhibition of Maine artists, they would mount one of Smalling photographs from the book, which are on view at Bowdoin now until August 25.

“At First Light: Two Centuries of Maine Artists, Their Homes and Studios” documents the residences of 26 creators, past and present, who have worked in Maine. To find them, Smalling crisscrossed the state, ultimately driving 5,856 miles. He began visiting artists who were still working at the time (some have since died), including Katz, Wegman, Driskell, Tuttle, Indiana, Jamie Wyeth, Ashley Bryan and Lois Dodd.

He tracked down the now-late Molly Neptune Parker, a celebrated basket maker and member of the Passamaquoddy Tribe. The interior of her modest mustard-colored ranch house in a part of Princeton, Maine, named Indian Township displays dozens of her whimsical, intricate strawberry- , corn- , acorn- and flower-topped baskets.

“To be able to go to their houses while they were there and to spend time with them made it so much more personal and immediate,” Smalling says.

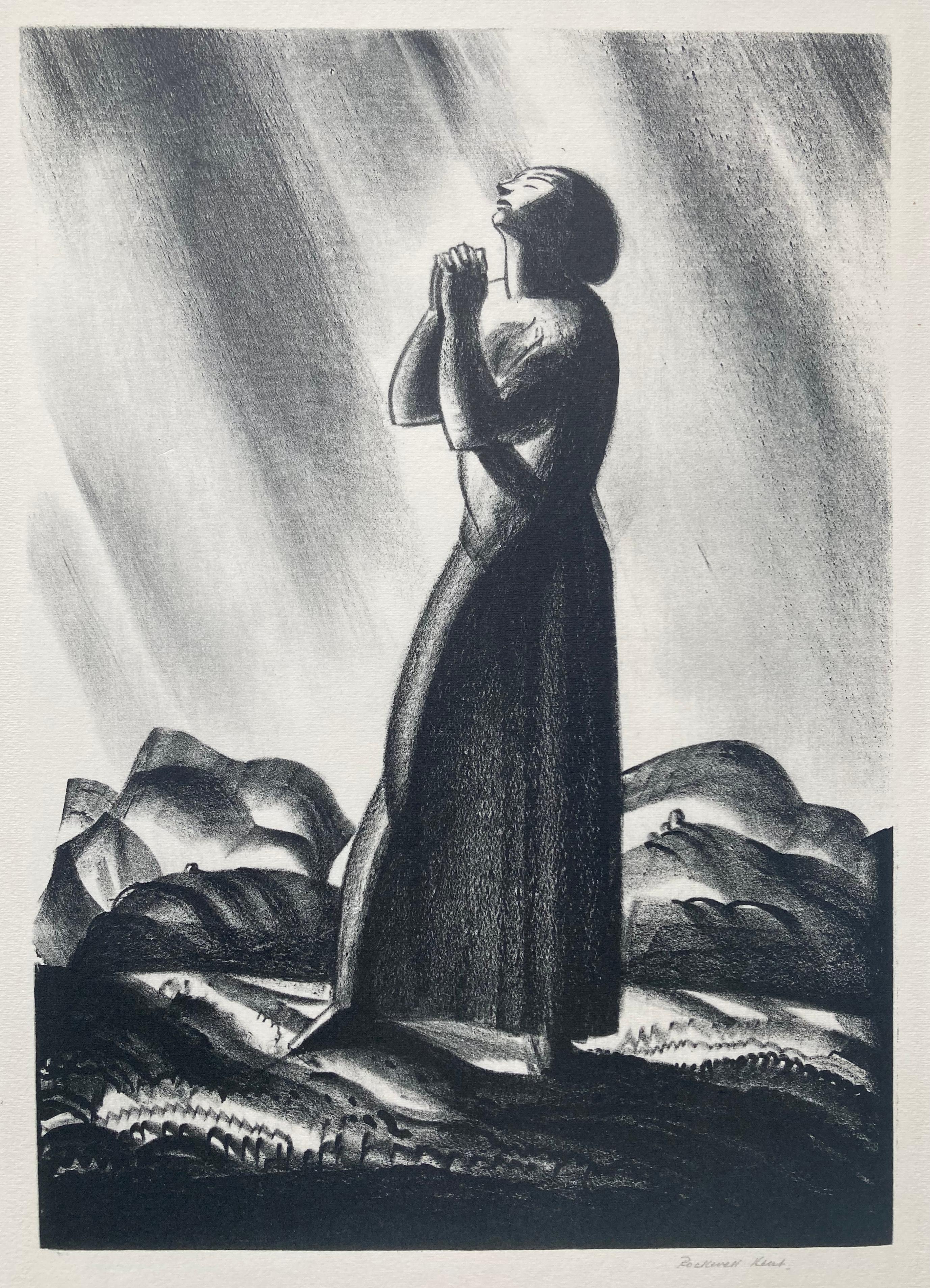

Indefatigable, he contacted the state historian of Maine at the time, Earle G. Shettleworth Jr., to find the studios of the 18th-, 19th- and early-20th-century artists. Five are open to the public: Congregational minister Jonathan Fisher’s yellow colonial in Blue Hill, which he built with the help of his parishioners in the early 1800s and is filled with fine American antiques, hooked rugs and his paintings; Homer’s wood-paneled, shingle-style carriage house in Prouts Neck, to which he added a second-floor balcony to study the coastline and the sea; Rockwell Kent’s modest Cape Cod on Monhegan Island; native Mainer Bernard Langlais’s shingle-style house and tool-filled sculpture studio in the Langlais Sculpture Preserve in Cushing; and the proud three-story house with Shaker-like interiors on the farm of Andrew Wyeth’s friends the Olsons, also in Cushing, where he is buried just in front of the family cemetery overlooking the Georges River.

“I was surprised how many of these homes were still standing in little corners throughout the state and could still add to our appreciation of what it means to make art in this part of the world,” Smalling relates.

“Because I have often done work as a photographer in historic preservation, going to old houses belonging to artists from the past felt very familiar,” he continues. “I have a system: I go into a house and sit down and wait till the place speaks to me and I hear those voices from the past. I can see what eyes had seen sometimes a hundred years ago, sometimes decades — what brought people here and what inspired them.”

Smalling hunted down the studios of deceased artists like Eliot and Fairfield Porter and Rudy Burckhardt. And he convinced the current owners of former artists’ studios to let him remove enough of their possessions to focus on the original bones of the house.

He also had some great luck. Although the Ogunquit home of Charles Herbert Woodbury has a new occupant, the artist’s grandsons live nearby and happily repatriated the things they had inherited: Woodbury’s easels, paintings, ship models, sculptures, textiles and objects. The grandsons placed the artifacts in the studio where they remembered them for Smalling’s photo shoot.

“A house is a manifestation of a person. Because Maine is such a singular place and has some incredible old houses, you can often tell quite a bit from seeing how people lived,” Smalling says.

“The people who were attracted to Maine were a rarefied group, maybe even a little wacky,” he adds. “There’s a lot of wildness. Maine’s ruggedness, its beauty and its light did shape people.”

Anne Goodyear concurs: “These artists have helped define how we understand this part of the world. And we are only scraping the surface,”

She points to the most recent piece in the show, a 2020 video by Erin Johnson, titled Lake, that presents a birds-eye view of a group of artists swimming. “Their coming together and breaking apart has a metaphorical quality that represents the dynamics of the artistic community here,” she says.

That community encompasses hotspots all over the state. “They support each other over multiple generations,” Goodyear adds. “Maine seems to be a place that people hold close.”