February 2, 2025When it comes to names of art movements, there are those that sound exactly like what you see: Impressionism, Abstract Expressionism, Pop art. Others lodge in the mind because of their strangeness: Dada, Ashcan School, the Blue Rider. And some are more cryptic, neither clearly descriptive nor particularly memorable: fauvism, postmodernism, Op art.

Orphism would fall into the last camp. The term conjures images of a rare congenital bone deformity, the digestive action of soil bacteria or a revolution of children seeking emancipation from their parents. Yet orphism is about pure beauty!

Parisian poet, critic and cultural provocateur Guillaume Apollinaire coined the term in 1912, drawing a parallel between the Greek mythological poet and musician Orpheus — who could sway nature and defy death through song — and a group of artists pushing the boundaries of visual representation.

He aimed to distinguish the orphists’ lyrical creations from the more cerebral, clinical brand of Cubism practiced by Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque and the like.

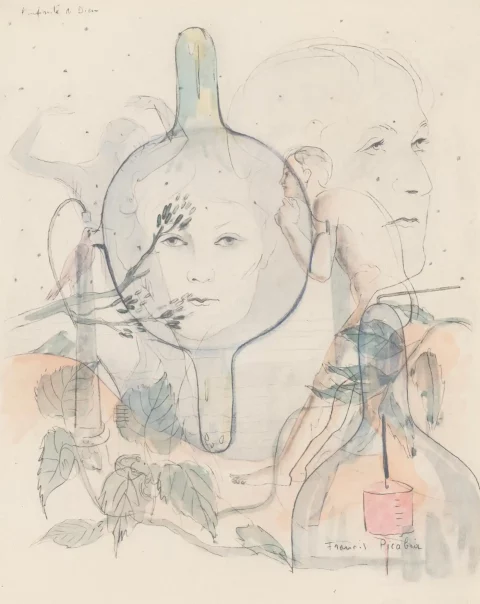

“Harmony and Dissonance: Orphism in Paris, 1910–1930,” on view at New York’s Guggenheim museum through March 9, offers an exuberant exploration of this brief but influential movement. The show features colorful masterpieces by Robert and Sonia Delaunay, František Kupka, Francis Picabia, Fernand Léger, Thomas Hart Benton, Marc Chagall, Marcel Duchamp and other luminaries of that era, alongside archival material that places orphism in the context of early modernism and the period’s scientific advances.

Orphism was neither a true movement, with a manifesto, nor a self-defined group — it was more of a vibe. “They were artists who knew each other by showing in the same exhibitions and going to the same salons,” says Vivien Greene, the Guggenheim’s senior curator of 19th- and early-20th-century art. Still, the pieces in “Harmony and Dissonance” are surprisingly cohesive.

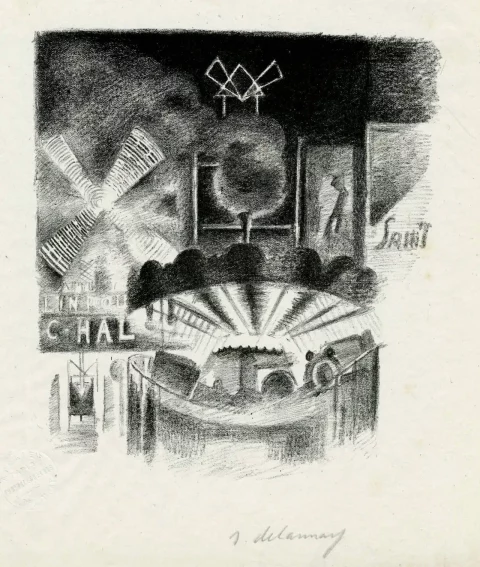

Standout works include Kupka’s Amorpha, Fugue in Two Colors (1911–12), a vivid abstraction often compared to a symphony, and Robert Delaunay’s Simultaneous Contrasts: Sun and Moon (1913), which uses concentric circles to evoke celestial balance. The exhibition brims with color, rhythm and a spiritual embrace of abstraction, capturing a moment when Paris was the pulsing heart of artistic innovation.

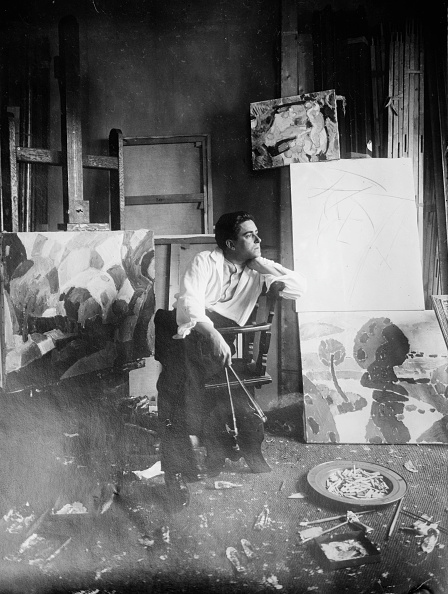

Key to orphism’s identity was Apollinaire himself, a larger-than-life figure who played at the intersection of poetry, art criticism and bohemian galavanting. Born in Rome to a noble (he claimed) Polish mother and an Italian father, he made his way to Paris in 1899, where his wit, charisma and hustle pulled artists, dancers, actors and scribes into his orbit. “Back in that era, poets and writers had a lot of power,” Greene says. “News, of course, was disseminated through the written word.”

Apollinaire coined not just orphism but also Cubism and Surrealism, and he was an early champion of the creators and movements that would go on to define modernism. His musings and close friendships with figures like Picasso, Duchamp and the Delaunays made him both an advocate for and collaborator in their creative experiments.

It’s hard to imagine an equivalent cultural force today — someone who was simultaneously an influencer, an intellectual and an artist in his own right. Apollinaire’s role in promoting orphism was pivotal, as he poetically made a case for abstract art as the next big leap in visual expression and a bridge between science and spirituality, technology and emotion.

Orphism thrived in a Paris pulsating with creative energy. At the turn of the 20th century, the city was a magnet for artists from across Europe and beyond. Figures like Kupka, from what is now the Czech Republic; Sonia Delauney, from modern-day Ukraine; Picabia, from France; and Stanton Macdonald-Wright, from the United States, converged in the city’s salons, cafés and ateliers.

The Delaunays’ studio became a hub where the Orphists and the Blue Rider expressionists, including Paul Klee, Franz Marc and August Macke, exchanged ideas.

The City of Lights must have felt downright futuristic at the time. The Paris Exposition of 1900 showcased technological marvels like electric lighting, a moving sidewalk, the Métropolitain subway system and the Ferris wheel — whose circular form directly influenced orphist compositions. “The Ferris wheel was a symbol of the modern and what engineering could do,” says Greene. “It was huge and dominated the Paris skyline along with the Eiffel Tower, so they get referenced quite a bit in the works in the show.”

The city hummed with the new sounds of ragtime, experimental orchestras and early jazz, and its streets were alive with avant-garde theater, couture fashion and busy cafés. “The idea of syncopation versus rhythm in jazz impacted how the orphists created their compositions,” Greene notes. This edgy scene made Paris an irresistible draw for young weirdos seeking acceptance and inspiration.

One of the most striking features of orphist art is its obsessive use of circles, disks and rings. These forms appear in works by the Delaunays, Kupka, Picabia and even the more figurative painters, like Chagall, Benton and Paul Signac. Why circles? The Ferris wheel was one influence, but so were the scientific color wheels developed by theorists like Michel-Eugène Chevreul and Hermann von Helmholtz. Then there were the hypnotically patterned spinning disks used by early psychologists in their practices, which mesmerized the orphists.

The Guggenheim exhibition includes Sonia Delaunay’s Electric Prisms (1914), a shimmering scene of fragmented circles and radiant hues, and Kupka’s Disks of Newton (1912), inspired by Isaac Newton’s experiments with light.

For the Orphists, circles symbolize unity, infinity and harmony. They constituted a visual language through which the artists sought to convey such intangibles as music, motion and metaphysics. Where Cubists fractured figures and forms, orphists sought to integrate them, using color and rhythm to evoke a sense of cosmic order.

They depicted the material cosmos, too. “Suddenly, artists, not just scientists, had access to telescopes, through which they saw planets and other astronomical bodies,” Greene explains. “So, this idea of the cosmic in the skies is also playing into the circles.”

Orphism had a sacred dimension, as well, reflecting the era’s fascination with the occult, mysticism and Eastern philosophies. Many orphists were influenced by theosophy, a spiritual movement that sought to reconcile science and religion.

“Kupka believed himself to be a seer,” with psychic abilities, the curator says. “He was interested in the other side of the cosmic coin.” His art often hints at hidden meanings, whether through symbolic colors or compositions that evoke ethereal energies.

Even in their more down-to-earth works, orphists pushed boundaries. Sonia Delaunay’s Simultaneous Dress (1914) bridged fine art and functional fashion, while her husband’s The Cardiff Team (1913) portrayed a rugby match as a kaleidoscope of color and motion, with the Eiffel Tower and Ferris wheel looming more concretely in the background.

Despite its brilliance, orphism had a short run. By 1914, its leading figures had largely moved on, and the onset of World War I disrupted the Parisian art world. The Delaunays decamped for neutral Spain and Portugal, where Robert took a break from abstract painting and Sonia turned to folk crafts and textile design; Picabia and Duchamp shifted toward Dada, highlighting the ridiculousness of life in a mechanized world; Benton ditched abstraction altogether and returned to the U.S. to found the realistic Regionalist style along with Grant Wood.

The war’s devastation and the cultural shifts it brought made the beauty and idealism of orphism feel out of step with the postwar mood. “Even the Cubists left the fragmentation of the human form behind because of all this breaking apart,” Greene says. “People wanted to be whole again.”

Although short-lived, orphism left a major mark on modern art. Its use of vibrant color and foregrounding of abstraction influenced movements from the Bauhaus to Op art (short for Optical art).

Near the end of the Guggenheim show, Irish abstractionist Mainie Jellett’s Painting (1938) offers a quiet yet powerful postscript to orphism. Gloomy blue, black and gray rings dominate the canvas, but a radiant rainbow manages to brighten one quadrant. It’s a glimmer of hope in a world transformed — not just by modernity but also by having survived one global war as another was about to begin.