October 23, 2022Growing up in Arkansas, LaToya Hobbs loved to draw, but she had little exposure to Black artists or images that reflected her own culture, aside from the family photographs that hung throughout her house. When she got to the University of Arkansas, her art history survey courses weren’t much help either. “I was taking a drawing class, and we had to bring in a book of work by a favorite artist, so I brought in one on Michelangelo because that was an artist I knew,” she says with a laugh. “I hardly knew of any artists of color.”

Everything changed when a professor introduced her to the work of Elizabeth Catlett, the acclaimed 20th-century Black printmaker who depicted African American (and, later, Mexican) life. “He asked me why I was looking at all these dead white male artists when the imagery I was making was so different,” she recalls. “Catlett was the first artist where I was like, ‘Wow, this work reflects me, and I see the women in my family and so many wonderful things about how she’s depicting Black women.’ And then there is the technical mastery of her craft. The work spoke to me on so many more levels and really encouraged me to delve into printmaking.”

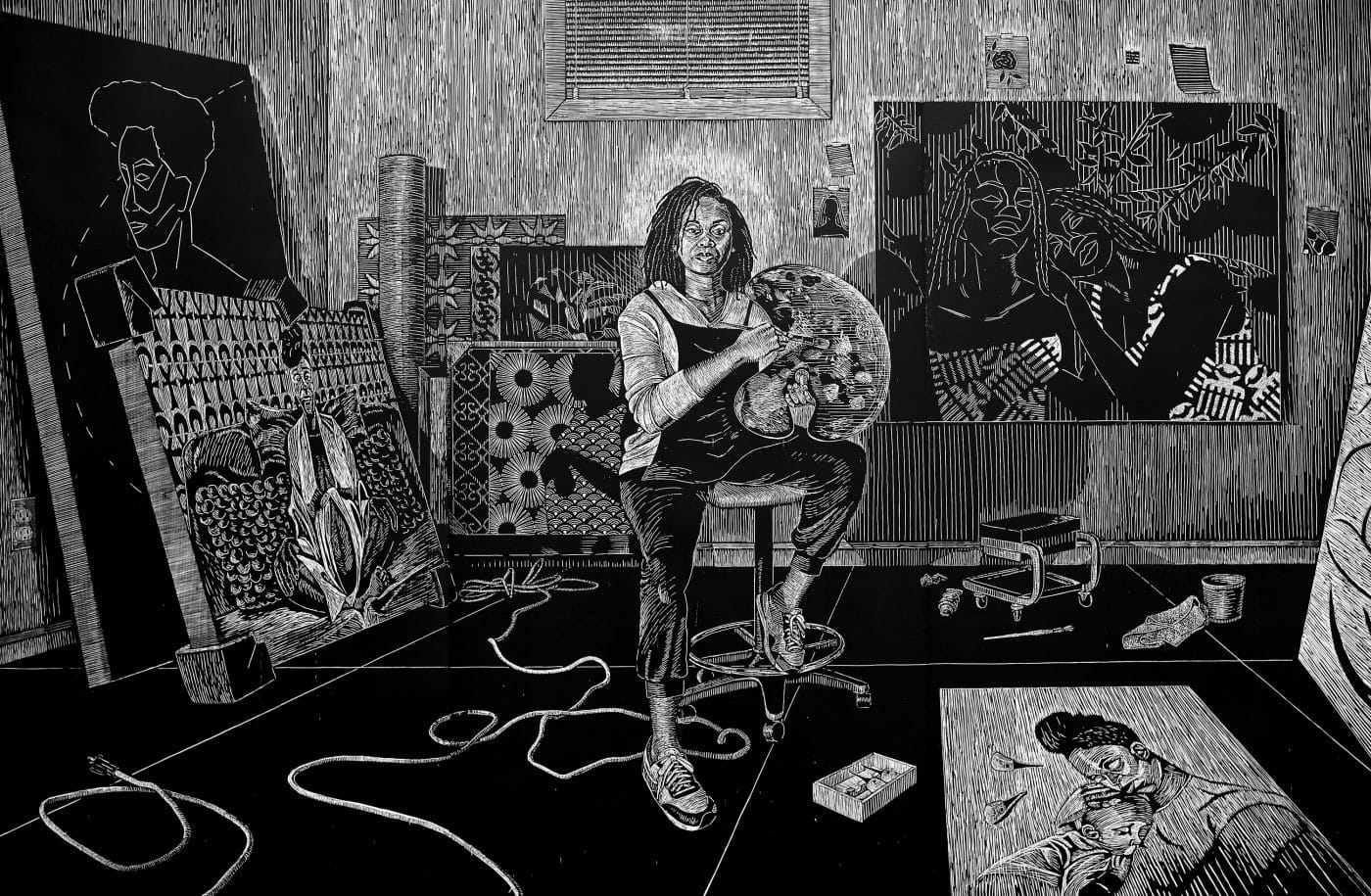

Fast-forward a decade or so, and Hobbs is now a printmaking virtuoso, as well as a professor at the Maryland College Institute of Art (MICA), where she teaches drawing, and a founding member of the collective Black Women of Print. Her rich artistic practice is anchored by woodcut images of family, friends and others close to her heart.

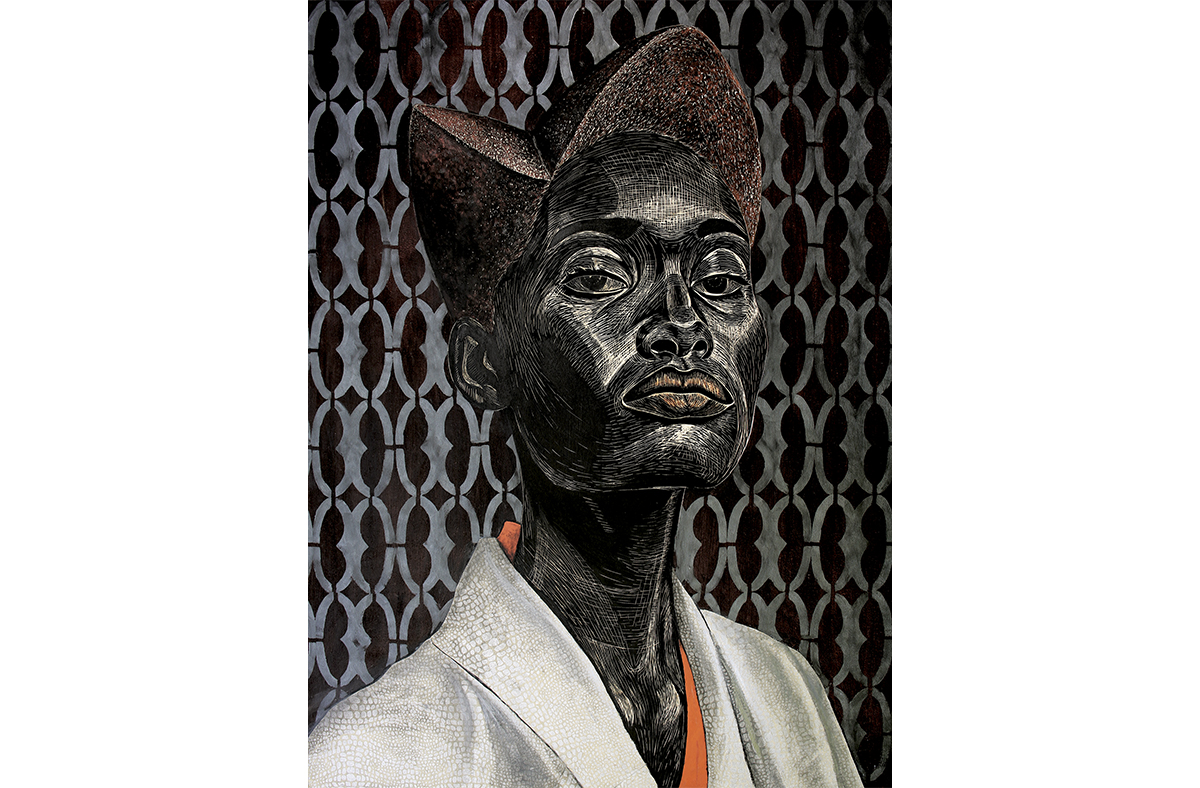

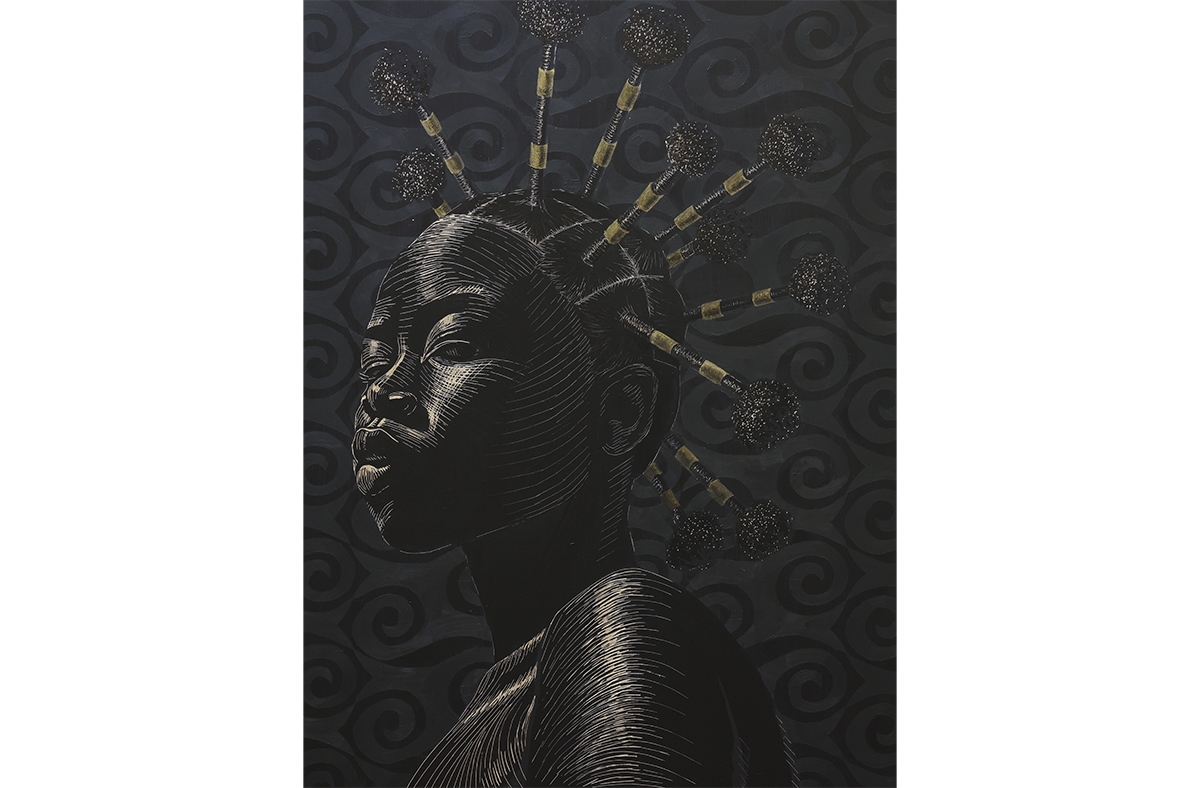

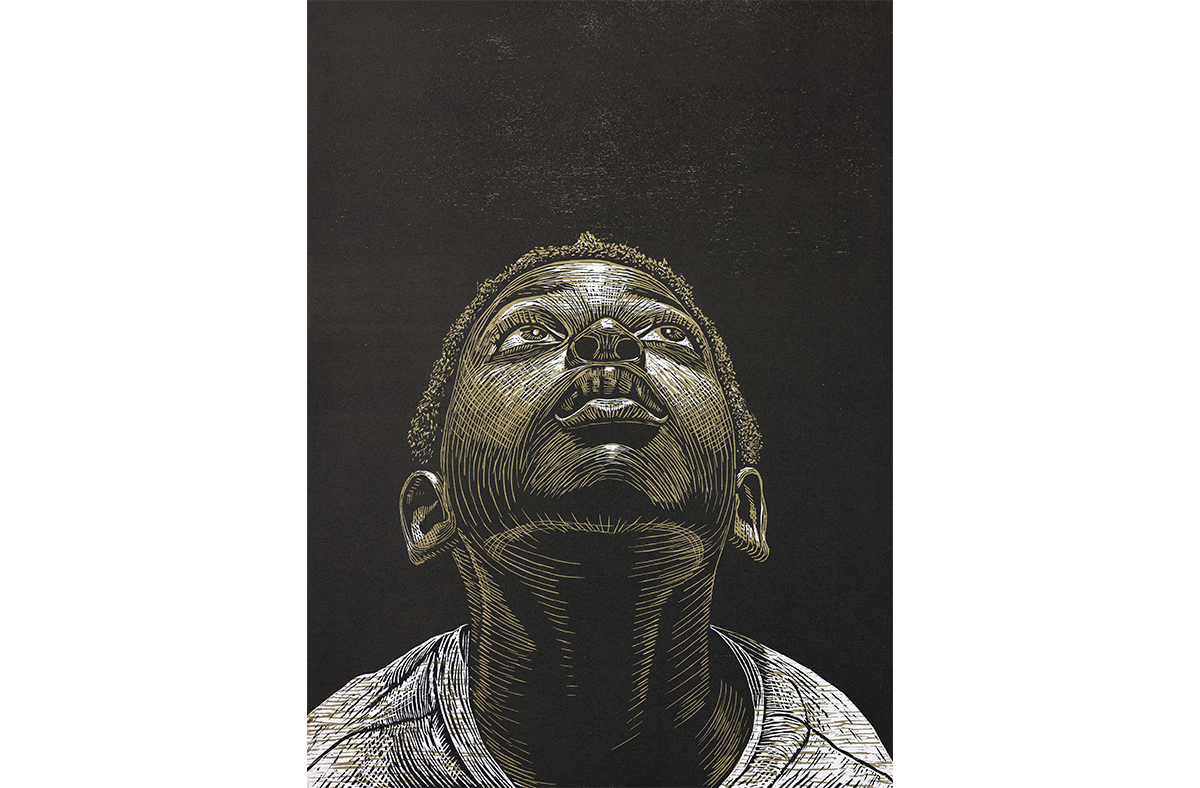

Hobbs earned her MFA in printmaking from Purdue University and has produced dozens of woodcut prints on paper. Recently, she’s also been working on an outsize scale and letting the carved-wood panel stand alone as a finished work of art. “I’m activating the surface of the wood panel the same way I’d do a woodcut, but for me, the functionality of it is as a painting. Sometimes, I do both — I carve the block, print from it and then go back to the block and paint it or collage it,” she says.

Hobbs is unveiling one of her most challenging and complex panels yet at the International Fine Print Dealers Association’s Fine Art Print Fair, which returns to the Javits Center, in New York City, from October 27 to 30 after running virtually for the past two years. Commissioned expressly for the fair, with support from the IFPDA Foundation as part of an ongoing collaboration with Black Women of Print, the monumental Genette’s Daughters shows six young Black women Hobbs knew as very young children, carved in relief.

“I came across the image on Instagram earlier this year,” says the artist, who drew the likenesses by hand on an 8-by-12-foot panel that had been painted black and then developed it tonally — “like a charcoal drawing,” she explains — through thousands of laboriously hand-carved marks and lines. She added in textures and patterns and altered some of their outfits to better suit their positioning and the monochromatic medium. Like many of her other portraits, the image combines the traditional handmade feel of the woodcut with the language of photography. The women stand as though posing for the camera.

“They were all very little children when I last saw them,” says the artist. Their mother was a pastor at the church Hobbs attended while in college in Fayetteville, Arkansas. “I remembered them as babies or very little kids, so seeing this picture was nostalgic for me. But it also connects to themes I’ve been talking about in my work — different facets of womanhood and family legacy. I’m thinking about what Pastor Genette signified to me as a spiritual leader but also as a powerful, dynamic and graceful woman and mother, about what it means to be a matriarch in different communities and about myself as a matriarch.” (Hobbs, who is married to fellow artist Ariston Jacks, is the mother of two young boys, ages 6 and 8.)

“Genette’s Daughters kind of turns the print world on its head by revealing not the print but the matrix as the art object,” says IFPDA executive director Jenny Gibbs, who also points out the multiple readings of matrix here, “with its Latin origin meaning ‘mother.’ ”

For Hobbs and her cohort at Black Women of Print, the artists who blazed the trail ahead of them are also matriarchs to be reckoned with. “We refer to them as our foremothers,” she says. The group was established in 2018 by the Milwaukee-based artist Tanekeya Word to bring visibility to creators like them. In 2020, the collective produced its first print portfolio, Continuum, which pays homage to those influential forebears via seven original portraits, each produced by a founding member of the collective. One of the 13 editions resides in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where it is currently on view.

Hobbs chose to depict Margaret Burroughs (1915–2010), the influential artist and writer who established Chicago’s DuSable Black History Museum and Education Center in her home. “Her piece Mother Africa really stuck with me,” says Hobbs. “It was the first example I saw with stippling instead of lines to create the image, so I emulated that.” Other members represented Catlett, Emma Amos, Wanda Ewing, Belkis Ayón Manso, Betye Saar and Alison Saar.

Earlier this year, Hobbs took the initiative to honor the founding members of the collective with portraits of their own. The IFPDA is showcasing that series of mixed-media paintings at the Fine Art Print Fair, as well. “I had a personal goal to do these portraits as a way to celebrate and commemorate the historic nature of the group,” she says. “There hadn’t been a collective of Black women printmakers before.” Each of the seven relatively large, 36-by-24-inch works is carved, collaged and brightly painted, demonstrating Hobbs’s skill with pattern and color. “We talk a lot about documenting our history because there hasn’t been much scholarship around Black women printmakers,” she notes. “We’re trying to remediate that.”

In conjunction with the fair, Hobbs has curated a special collection for 1stDibs Auctions. While she has a keen interest in her fellow printmakers and Black artists, she continues to find inspiration all over, in areas ranging from the Old Masters that first fed her love of art to digital photography. When invited to choose pieces from the vast trove of art available on the platform, she assembled an assortment of works that show the breadth of her interests. “I didn’t want to stick to just prints,” she says, although she does include some gems. Among them is Elizabeth Catlett’s 1983 linocut print Survivor, which the artist based on a photograph by Dorothea Lange, Ex-Slave with a Long Memory, taken around 1937 in Alabama when Lange was documenting rural poverty for the FSA.

Hobbs’s selection is largely figurative and reveals her particular interest in the body and how it moves, which comes, in part, from practicing dance for many years. Take the 2004 color lithograph after Surrealist René Magritte’s La Folie des Grandeurs II or Jeanloup Sieff’s 1983 black-and-white photograph Intimode – Les Dessous de la mode.

Through her collection, she’s also drawing attention to several young Black artists working today, such as Nigerian printmaker Nneka Chima and New Orleans–based photographer Trenity Thomas.

In 2020, as part of her effort to make visible the lives and accomplishments of all Black women artists, past and present, and explore her own relationship with motherhood, Hobbs embarked on an epic family portrait. Titled Carving Out Time, the work unfolds in five monumental woodcut panels. “It’s literally a documentation of our day,” says the artist. We see her with her husband and two sons as mother, wife, practicing artist and educator.

Hobbs based the realist images on photographs taken expressly by Jacks at various moments from morning to bedtime. “We picked a day, and my kids were a part of the process. We asked them to pick out the pajamas for Mommy’s artwork,” she recalls. It’s an intimate view on a grand scale of the busy life of an artist, and it feels just as personal as it does universal.

The panels, which each measure 8 by 12 feet, were Hobbs’s first foray into the carved format on a grand scale — an evolution inspired by the artist Kerry James Marshall, she says. In 2014, she came across his massive woodcut on paper Untitled (1999) in the acclaimed traveling exhibition “30 Americans.” That work depicts a casual social gathering of Black men inside a home, spread across 12 large panels.

“I had never seen any type of woodcut done on that scale,” she recalls. “It was a mind-blowing experience.” Jacks encouraged her to scale up, “but I didn’t think I was capable at the time,” she says. After seeing Marshall’s massive work again, in 2019, she gave it a go and produced the family portrait.

The monumental Gennette’s Daughters at the IFPDA fair is the next step for her. “I thought capturing six life-size figures would be a really challenging thing to do,” she says. For all the seeming simplicity of a family photograph, it is extraordinarily complex in its arrangement of marks. Hobbs may be hoping to document history, but she is clearly also making it.