February 1, 2021The power fist is an unmistakable symbol of the fight for racial justice, one that has been potently employed by Black Lives Matter protestors. In this context, it’s no wonder that Black Unity (1968), a two-foot-wide mahogany fist sculpted by the late artist Elizabeth Catlett, has taken on new resonance.

The work was featured in the much-lauded exhibition “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power,” which opened at the Tate Modern in London in 2017 and has since traveled to major museums in U.S. cities from Brooklyn to Houston, Bentonville to San Francisco.

When the show opened, the sculpture graced the cover of Artforum. It’s a key example of Catlett’s artistic mission. “I have always wanted my art to service Black people,” she once said, “to reflect us, to relate to us, to stimulate us, to make us aware of our potential.”

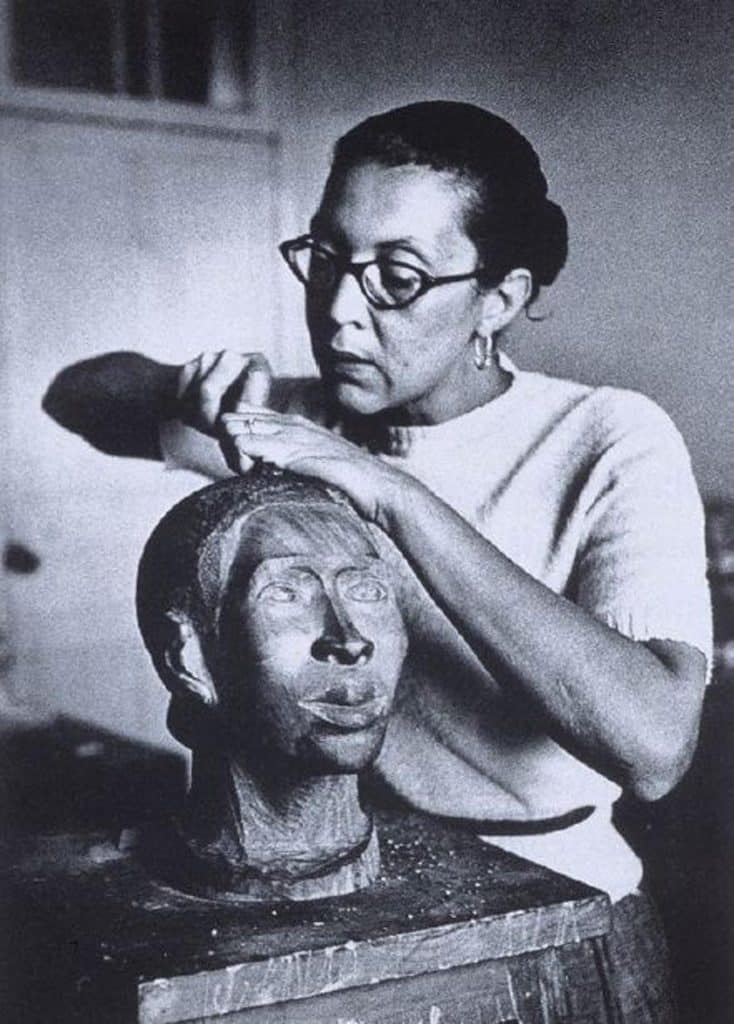

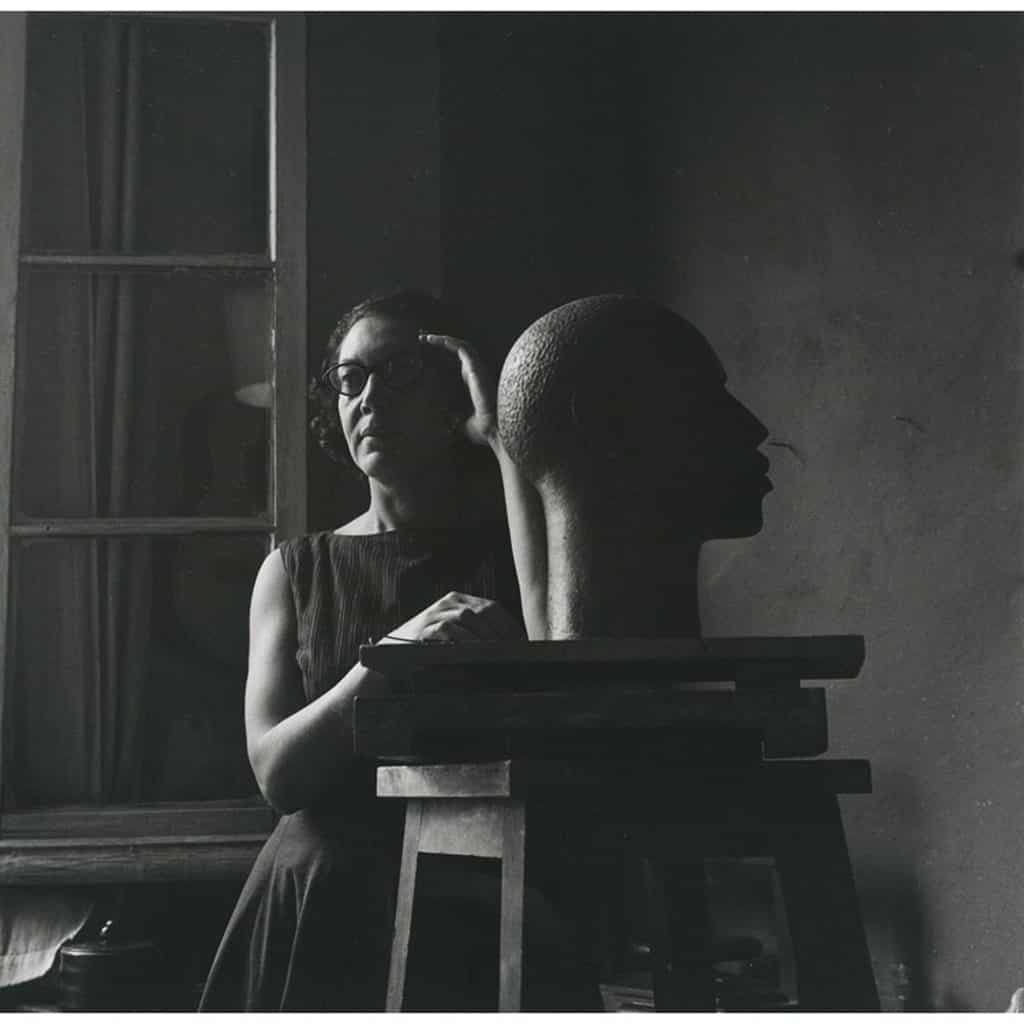

The exhibition and cover story exemplify the widespread attention Catlett, who died in 2012 at the age of 96, has garnered in recent years. She has long been a hero to African American artists and a favorite of African American collectors, and lately, her sculptures and prints has appeared in numerous exhibitions.

Alison Saar, who is well known for her sculptures inspired by the African diaspora, discovered Catlett’s work while studying with Samella Lewis at Scripps College in the 1970s. “Her work had a ferocity, in both her sculptures and her prints,” says Saar, the daughter of influential artist Betye Saar. “She was one of few Black sculptors exhibiting work at that time. I admired the large scale of her sculptures and her facility with large power tools, which she continued wielding even as she got on in years.”

Saar also makes prints and recently created a now-sold-out linocut to raise money for Black Lives Matter, depicting a woman with an Afro making a power fist. She has said she was thinking about the women of the Black Panthers as she made it.

“Catlett’s not as well known as she should be, because she was Black, because she was a woman and because she did most of her work in Mexico,” says Jacqueline Copeland, former director of the Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African American History and Culture, in Baltimore, and curator of that institution’s 2020 show “Elizabeth Catlett: Artist as Activist.”

The exhibition included 20 prints and 14 sculptures. “Her work addressed issues that are highly relevant today,” Copeland adds, “freedom, race, ethnicity, feminism. She fought oppression, racism, classism and gender inequality throughout her more than seventy-year career.”

Catlett has been called the foremost African American woman artist of her generation, a generation in which few women artists, let alone African American ones, attained recognition. She was born in 1915 in Washington, D.C., to a middle-class family — her mother was a school truant officer; her father, who died before she was born, a mathematician — which gave her certain advantages.

“I have always wanted my art to service Black people — to reflect us, to stimulate us, to make us aware of our potential.”

She majored in art at Howard University and, a few years after graduating, continued her studies at the State University of Iowa, where she was one of only two Black students in the art department. “In those days, women artists couldn’t just go to New York,” Copeland says. “They had to take unconventional paths, because they were more or less told they could never be mainstream.”

In Iowa, Catlett was mentored by Grant Wood, who encouraged her to depict the parts of life that she knew best. The master of fine arts program was newly established, and she was the first student to earn the degree.

After her graduation, in 1940, she got a job teaching art at Dillard University, in New Orleans, where she confronted segregation every day. Taking her students to the Delgado Museum (now the New Orleans Museum of Art), which was located in a park closed to Black people, was an act of defiance.

One of her students was Samella Lewis, who went on to become an artist and a preeminent scholar of African American art. Lewis wrote of her mentor, “She was a commanding and fascinating individual.”

Catlett spent a summer in Chicago, living with the artist Margaret Taylor-Burroughs and becoming involved in the South Side’s dynamic art community, which had been radicalized by the advance of fascism in Europe and the economic wreckage left by the Great Depression. One of its members was Charles White, who became her husband. In 1942, the couple moved to New York City, where Catlett encountered yet another rich artistic community, in Harlem.

She became friends with Jacob Lawrence and honed her sculpting skills at the Art Students League. “When you think of the important artists of that era that we know — Charles White, Jacob Lawrence and Romare Bearden,” Copeland says, “there were women who were also doing important work. They were overlooked.”

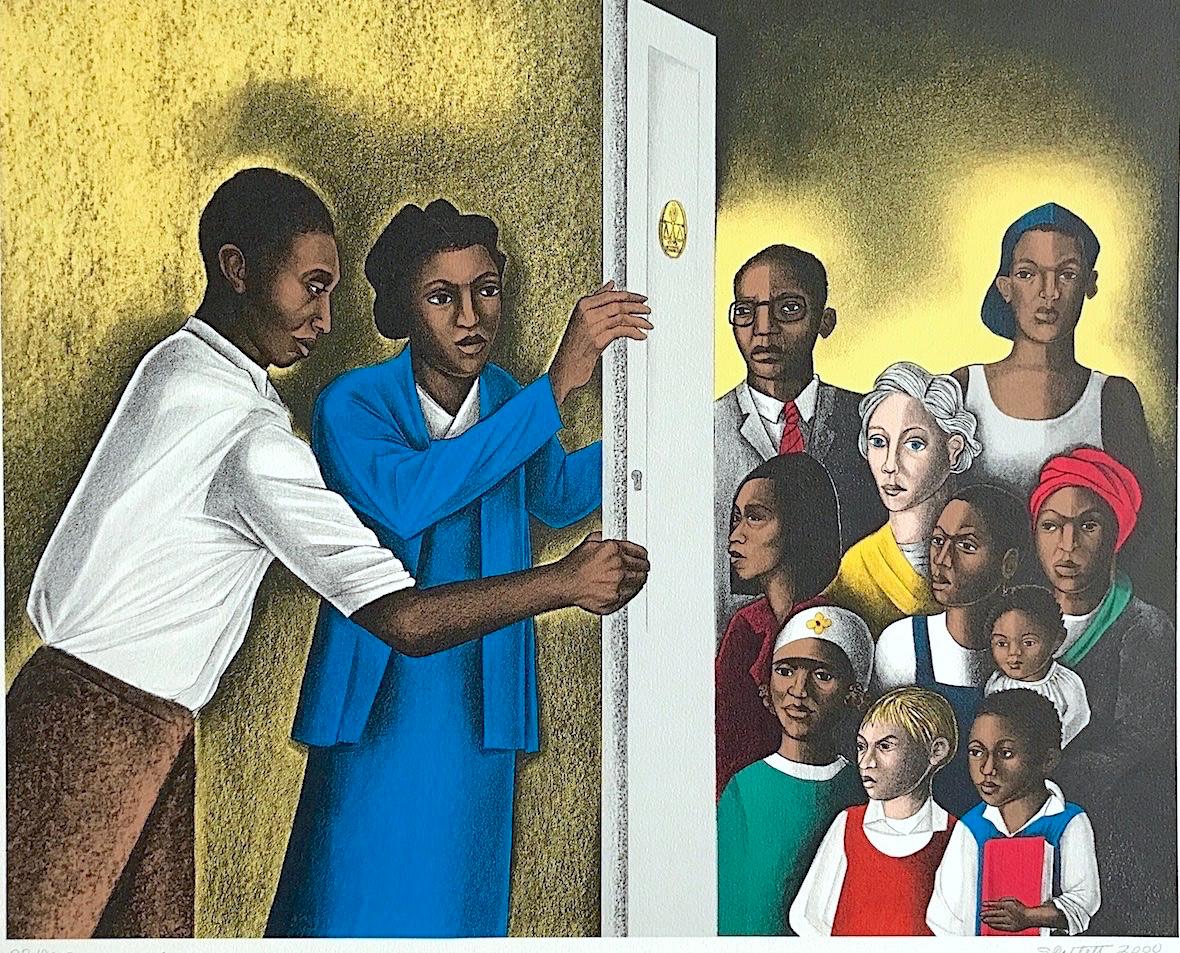

Teaching art at the George Washington Carver School, a community school for the working people of Harlem, she discovered that her students were, as she put it, “hungry for culture.” She left determined to create art that was accessible to all.

In 1945, a fellowship took her to Mexico, where she began collaborating with the Taller de Gráfica Popular. The socially conscious printing workshop created and distributed widely posters and inexpensive handbills whose iconography was easily recognizable to working Mexicans, many of whom were illiterate. Its populist fervor galvanized Catlett to “make art for her people” — African Americans — Copeland says. Catlett and White divorced, and she later married the Mexican artist Francisco Mora, with whom she raised three sons.

At the Taller, Catlett produced “The Negro Woman,” a series of linoleum cuts depicting the struggles of African-American women, among them, Sojouner Truth, Phillis Wheatley and Harriet Tubman.

The works are accompanied by a narrative. “I am the Negro woman. I have always worked hard in America. In the fields. In other folks’ homes. I have given the world my songs,” it reads, and later, “My reward has been bars between me and the rest of the land. I have special reservations, special houses, and a special fear for my loved ones. My right is a future of equality with other Americans.”

“Catlett’s ‘The Negro Woman’ is by far one of my favorite art series of all time. I am stunned every time I see those prints,” says Carolyn “CC” Concepcion, cofounder of the nonprofit cultural collective ARTNOIR. “The way she captured the emotion, the spirit, the resilience and the power of the Black woman is truly breathtaking.”

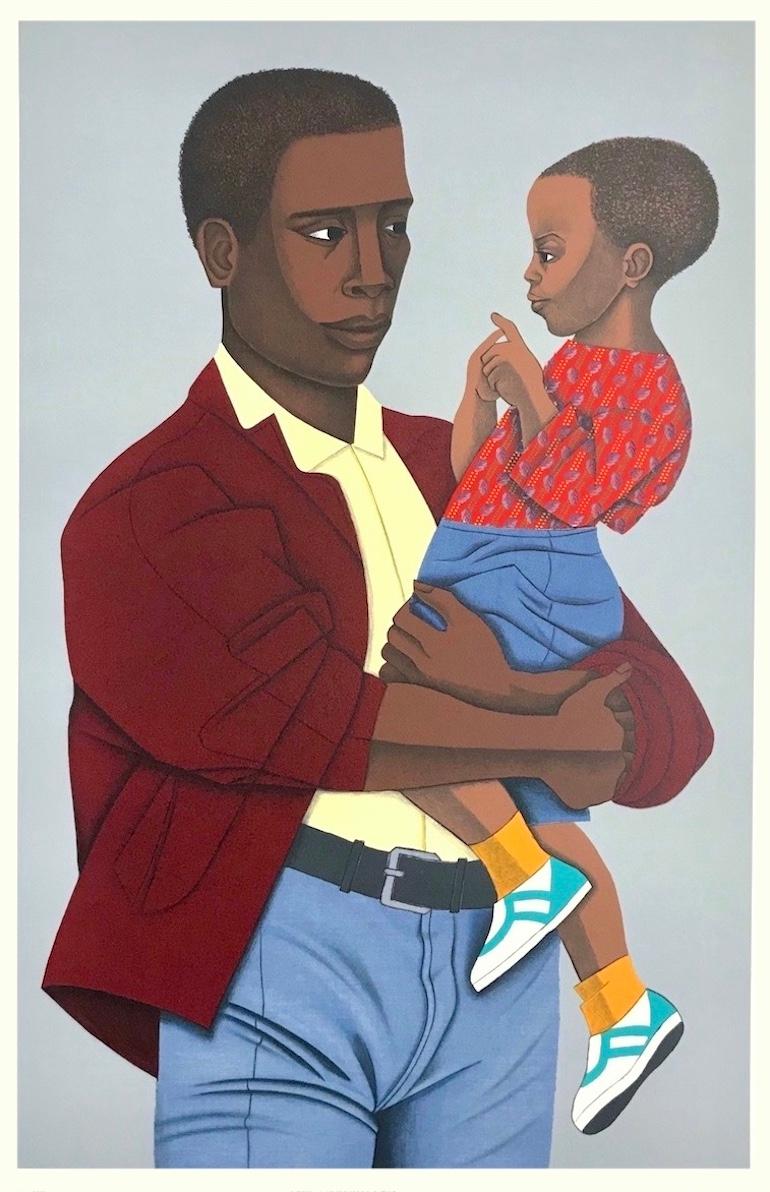

In 1952, Catlett created Sharecropper (1952). The now-iconic, exquisitely detailed print portrays a Mexican woman seen from below, giving her a heroic stature. She is clearly poor — a safety pin holds her jacket closed, and her broad-brimmed hat suggests she works in the fields — but her face conveys dignity. “That piece exemplifies all she believed in,” Copeland says, “that a person can have nobility, even if they are in the lower classes.”

When the House Un-American Activities Committee began its aggressive investigations of suspected Communists in the 1950s, Catlett sensed that her political sympathies might make her a target of government harassment if she returned to the U.S. Indeed, the Taller was classified as a “Communist front organization” and scrutinized by the U.S. embassy.

Catlett became a Mexican citizen in 1962 and was labeled an “undesirable alien” by the State Department. She was granted a special visa to attend her solo exhibition at the Studio Museum in Harlem in 1971.

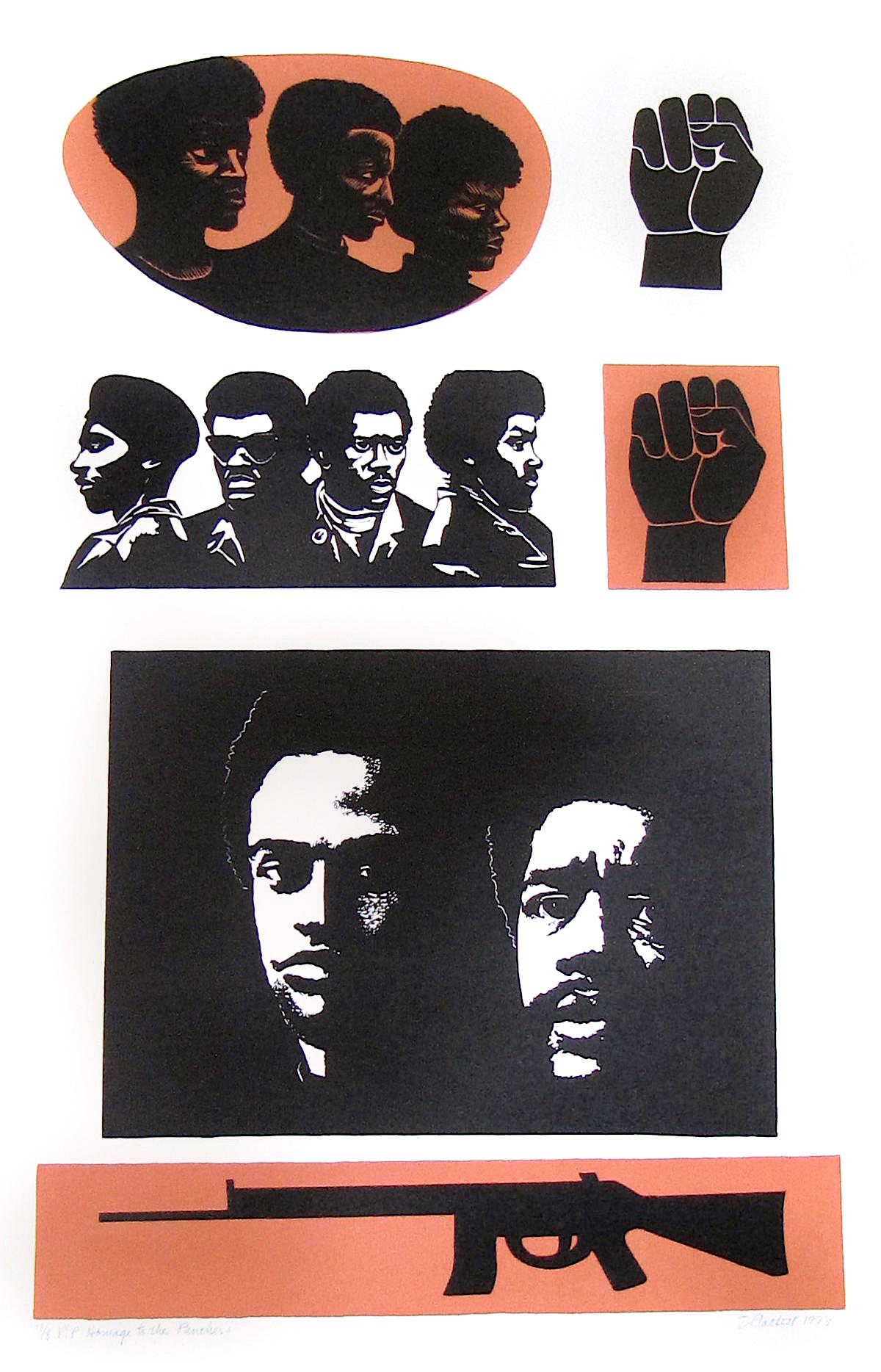

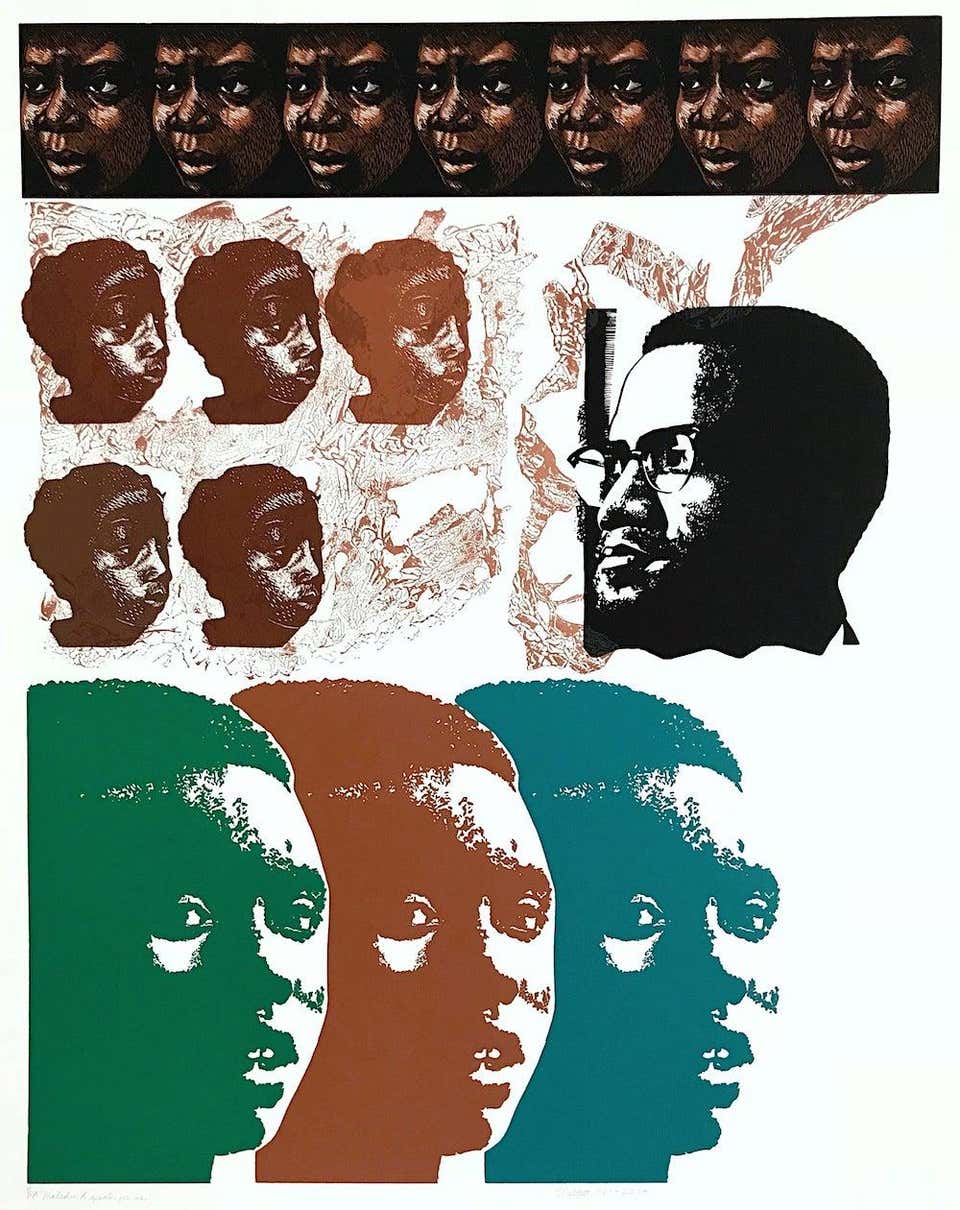

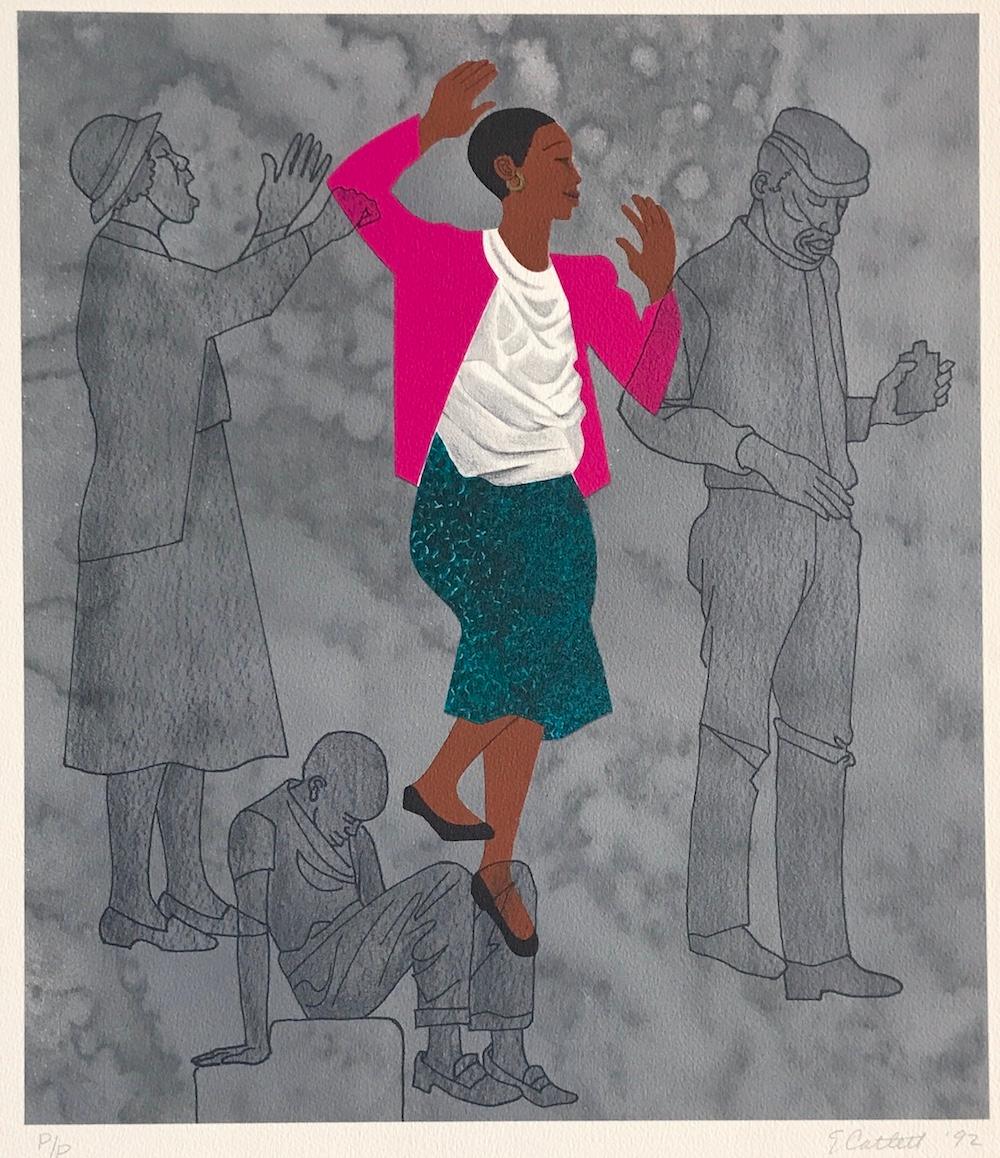

Catlett closely followed the Civil Rights Movement of the ’60s. In her prints, she depicted the Black Panthers, particularly the women, including Angela Davis. “She wanted the women to be recognized, which was unusual,” Copeland says. “The women were not only in support roles but were instrumental in forming the ideology.”

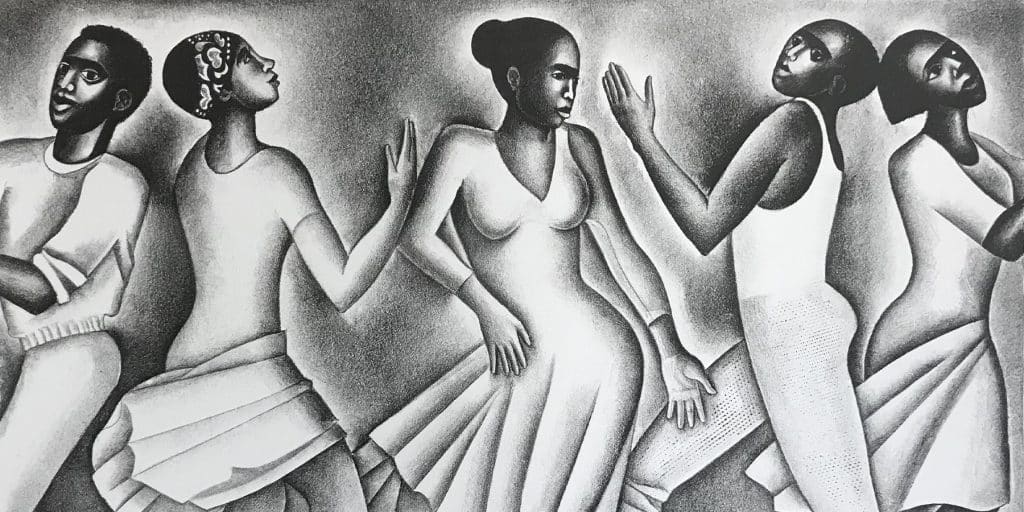

Catlett was also a prolific sculptor. Her elegant modernist figures are reminiscent of pieces by Henry Moore and Constantin Brancusi. Barry Malin, however, points to a crucial difference in his essay for a 2017–18 show of her works at his New York gallery. “Unlike Brancusi’s sculptures,” he notes, “Catlett’s communicate the importance of personal and social history. They retain the stamp of psychological encounters, the drama of race and class differences.”

In 1968, Catlett made Black Unity —undoubtedly inspired by the incident at the 1968 Olympics in which two medal-winning U.S. athletes held up their fists in protest during the national anthem — as well as a sculpture of a female figure holding up a fist, Homage to My Young Black Sisters.

She often chose women as the subject of her sculptures — depicting mothers embracing children, for example — her round forms evincing the influence of Mexican artists like Diego Rivera. And she worked masterfully in a variety of materials: mahogany, teak, onyx, marble, bronze. But it wasn’t until Catlett was in her 80s that she received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the International Sculpture Center.

Artist Letitia Huckaby, whose work combines documentary-style photographs of Black life in the American South with evocative materials like embroidery hoops and patchwork quilts, says it means a lot to her that Catlett always depicted Black women with great dignity. “There’s a delicacy to her style,” she says. “It’s very poetic.”

Last year, Huckaby and her husband, the artist Sedrick Huckaby, organized hundreds of volunteers to create a massive piece of protest art in Fort Worth: a 190-foot ground mural on Main Street that read, “End Racism Now.” Sedrick says Catlett has been a role model for him since he discovered her as a high-school student. “She had a strong intention for her art,” he observes, “and I always think that’s an amazing thing, to believe that art has the power to affect positive change.”

Catlett really did believe in the society-shifting potential of art. “Artists,” she once said, “should work to the end that love, peace, justice and equal opportunity prevail.”