October 13, 2019An exhibit of 50 of Michelangelo’s drawings at the Cleveland Museum of Art, on view through January 5, 2020, pulls from the collection of Teylers Museum, in Haarlem, the Netherlands. Many of the pieces have never before left Holland. Among the works on view is Studies of arms and hands, from 1513–14 (top). The show also include Portrait of Michelangelo, ca. 1550–51, by Daniele da Volterra (above). All images © Teylers Museum, Haarlem, unless otherwise noted

Michelangelo Buonarroti was born to minor Florentine nobility and, when barely a teen, was taken on as apprentice by the eminent fresco painter Domenico Ghirlandaio. He left that workshop after a short stint, invited to attend the Humanist academy for artists and thinkers held in the libraries and gardens of the influential Medici family.

When Florence, under the influence of the hyper-religious friar Savonarola, expelled the Medicis, in the late 1400s, Michelangelo fled as well. Michelangelo went to Bologna, then Rome, where his timelessly beautiful Pietà, now in Saint Peter’s Basilica, solidified his reputation. This was followed by David, in Florence, and in 1505, by a prestigious commission from Pope Julius II to create his tomb. This grandiose project, which was to include multiple supersize statues, fell prey to the clash between the two like-tempered giants. The pope, probably needing funds elsewhere, interrupted the construction, and the frustrated artist left to pursue other projects, only to be recalled in 1508 to begin the now-fabled Sistine Chapel paintings, whose completion took four years.

Left: Three draped figures, with hands joined, one kneeling, the others standing, 1496–1503. Right: Woman bending forward; five heads (after Giotto), ca. 1530–34.

The new exhibition “Michelangelo: Mind of the Master” — jointly organized by the Cleveland Museum of Art (where it runs through January 5, 2020); the J. Paul Getty Museum (February 25 to June 7, 2020); and Teylers Museum, in Haarlem, the Netherlands — tracks the brilliant, tumultuous career of this gifted, complicated man through an important group of his drawings. More than 50 in all, covering both sides of 28 sheets of paper, they offer remarkable insights into the artist’s major accomplishments in painting, sculpture and architecture, including the Sistine ceiling, the Last Judgement and the dome of Saint Peter’s.

Study of a mourning woman, ca. 1500–1505. Image courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

The lion’s share of the works in the show are on loan from Teylers Museum while it undergoes a major renovation. Acquired by the museum in 1790, they had been part of the collection of Christina, the queen of Sweden from 1632 to 1654, who loved art, refused to marry, rejected the overly feminine, studied briefly with Descartes and secretly converted to Catholicism from Lutheranism. In the course of ruling, abdicating and moving to Rome as a convert, she acquired several albums of drawings by Italian artists, which included this group of impressive work by Michelangelo.

In Various figure studies (verso), 1511, among the random, stunningly fine sketches scattered on the page, you cannot help but notice the hand gesture with which God sparks Adam to life in the famous scene depicted on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Woman bending forward; five heads (after Giotto) (verso), 1530–34, both honors and surpasses the work of the artist’s hero, Giotto. Also included is a rare portrait of Michelangelo by his student and friend Daniele da Volterra, showing the artist in old age, his blunt, slightly inelegant features animated by an expression that’s penetrating, inquiring and just a little sad.

According to Emily Peters, curator of prints and drawings at the Cleveland Museum of Art, only 600 or so drawings remain from the tens of thousands it is assumed the artist made. Many of the rest were burned by him in two bonfires, including one shortly before his death. “Michelangelo: Mind of the Master” gives us a precious peek at some of those rare works, most never before seen outside Haarlem. (Even the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s 2017–18 blockbuster “Michelangelo: Divine Draftsman and Designer,” which displayed more than 133 drawings, didn’t have access to the Teylers impressive holdings.)

Introspective recently spoke with Peters to get the stories behind the master’s drawings.

The exhibition displays some of Michelangelo’s studies for the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, in Rome’s Saint Peter’s Basilica, against a backdrop that replicates the finished ceiling.

What did each of the three institutions contribute to this project?

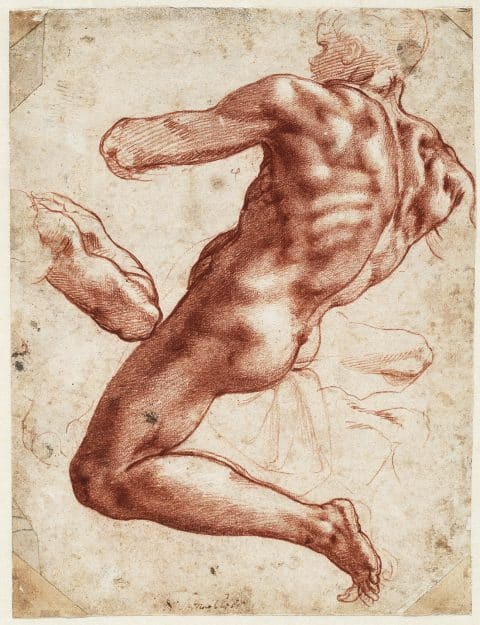

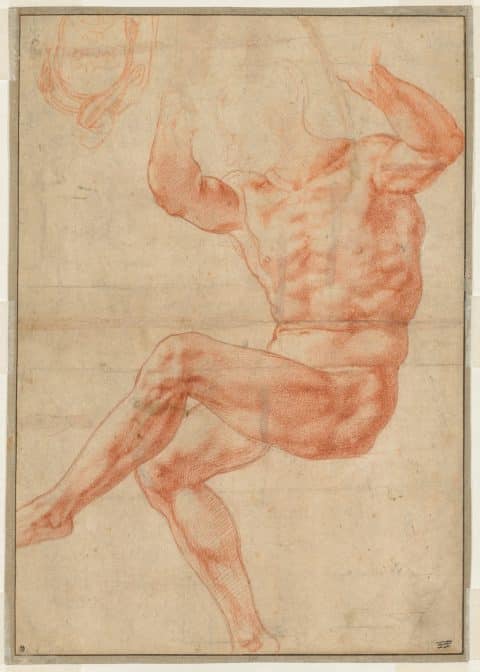

Of the twenty-eight drawings on display, twenty-five came from Teylers, two came from the Getty, and one important work came from the CMA, titled Study for the nude youth over the Prophet Daniel, a preparatory drawing for one of the ignudi on the Sistine Chapel ceiling made between 1510 and 1511 in red chalk over black chalk or charcoal added. The exquisite torso suggests the figurative style perfected in the Sistine ceiling. A head is sketched more loosely on another part of the same sheet. That was how Michelangelo worked. He studied each body part in isolation, in detail, almost as if he is flaying the anatomy visually to understand it, then putting all these insights together in his finished work.

Various figure studies, 1511

How did Teylers end up with these drawings?

Teylers Museum was founded in 1784, as the principles of the Enlightenment were just being shaped. It was a place with a great interest in the natural world. It has minerals, physical instruments, coins, medals and many paintings, drawings and prints by artists like Rembrandt and Michelangelo.

You might think it’s an unusual combination, but keep in mind that this is one of the Netherland’s oldest museums. Back in those days, science was also considered a form of art, and Michelangelo’s remarkable drawings aligned with all that.

Why would an artist acknowledged as a prodigy in his own day burn his drawings?

We know Michelangelo was very secretive and that he ordered his servants to burn his drawings at least two times. Because of his fame, other artists were intensely interested in his ideas, and he feared copyists. But it may have also been that his biographers and dedicated circle culled only the best sketches to reinforce his stature, to advance the idea that his talents were fully formed from birth.

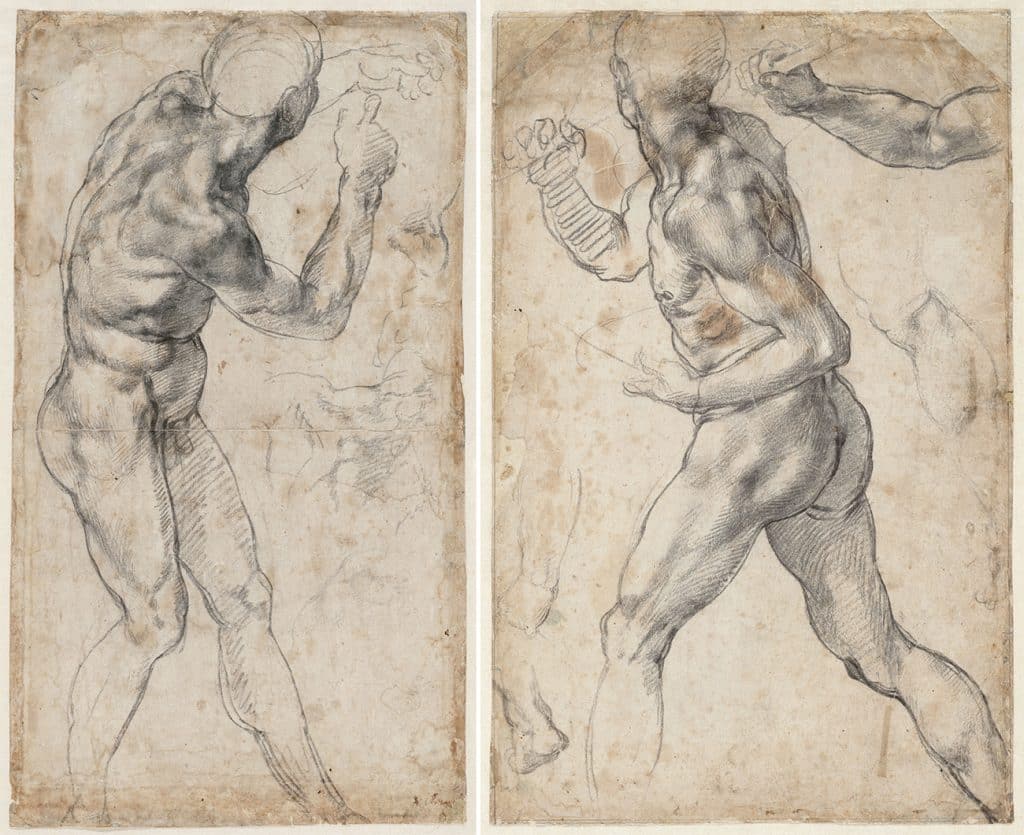

Left: Male nude, turning to the right; studies of anatomical details, 1504 or 1506. Right: Study of a striding male nude, to the left; studies of anatomical details, 1504

I am sure even his crudest studies were remarkable. How do we have the drawings that remain?

Because he was famous, many sketches left his studio. They were stolen or given as gifts to friends. A large group ended up in the estate of his friend Daniele da Volterra, but when he died, things got murky.

In the sixteen twenties, Joaquim von Sandrart acquired the drawings and sold them to a Swedish official named Silvercron, who provided them to Queen Christina of Sweden. We also know that these drawings were among the prized possessions she took to Rome when she gave up her throne.

Seated male nude, separate study of his right arm, 1511

Leonardo da Vinci dissected cadavers before Michelangelo and is famous for very detailed images of things like the optic nerve, the spine, a fetus in utero. What distinguishes Michelangelo’s drawings — in particular, the ones on view?

Michelangelo relied heavily on unusually finished drawings as his creative proving ground for larger projects. Partly through his influence — and that of his older contemporary Leonardo — close observational drawing from the nude became a required skill taught as a regular course of study by the Accademia del Disegno, which was founded in 1563, the year before Michelangelo’s death.

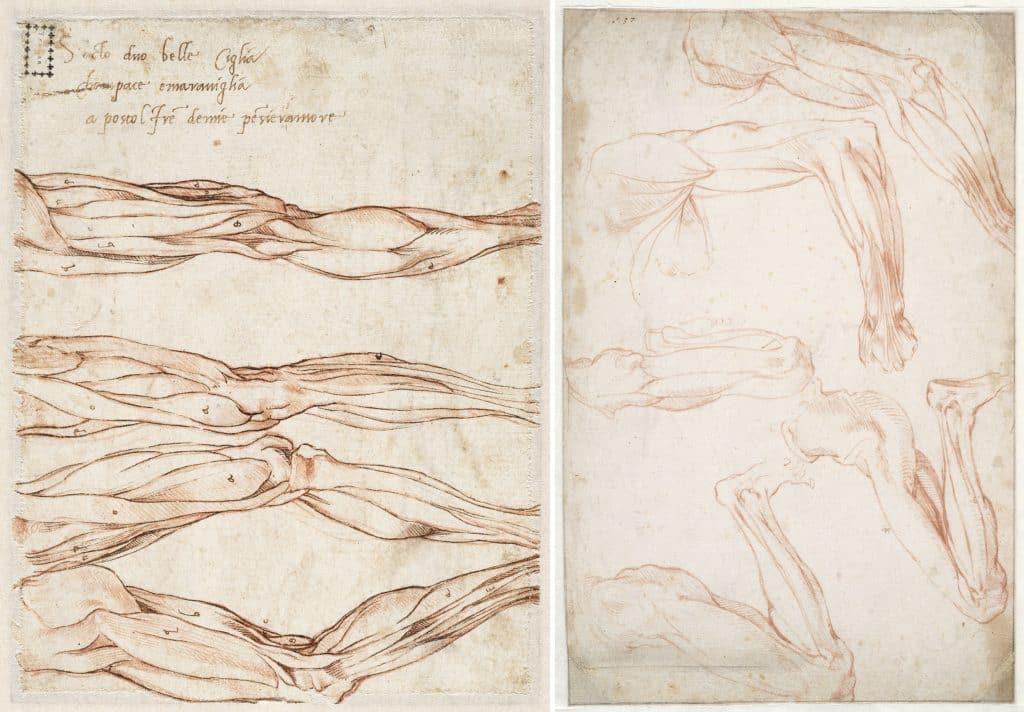

Leonardo was interested in organs in their own right, but what we see in the drawings on view is that Michelangelo was thinking like a sculptor. He observed and drew the muscles and joints of the legs and torso as layered fragments, as if he were trying to understand the origins of human motion and locomotion. That fascination with line and the mechanics of a non-static body distinguishes his more sculptural approach to the figure.

Left: Four studies of a leg, 1515–20. Right: Studies of a bent left leg and a bent left arm, 1515–20.

Study for the nude youth over the Prophet Daniel, 1510–11. Image courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art

That may be what produces the super-lyrical, flowing volumetric grace of the drawings on view.

His time with the Medicis exposed him to a vast collection of classical statuary, to Renaissance poets and scholars, plus the work of contemporaries like Donatello. This is when his work explodes, gets its “pow” effect, when it becomes monumental and uniquely his own. In 1502, Michelangelo is said to have seen the very emotional Hellenistic sculpture Laocoön in Rome, and its dynamism and power were revelatory for him.

There are several drawings related to the fabled Sistine ceiling.

The Sistine Chapel involved five thousand feet of images and some one hundred figures, all done by the artist himself. It was four years of serious toil. As we know, he was on a scaffold most of the time. His drawings from the first part of the Sistine commission, dating to between 1508 and 1510, are more scarce than those from the second half, between 1510 and 1512.

The drawings we exhibit are dated later, when Michelangelo came down from the scaffolding for the first time and began to really look at the images from the floor, from the viewers’ perspective. You can see in many of these drawings how he reconsiders the spatial demands, how he goes back in with dense, red chalk to make his lines and figures bolder, more readable from the angled, long distances from which they would be seen.

The Holy Family with Saint John the Baptist, 1525–early 1530s. Image courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

Is this when we begin to see him almost inventing the outsize scale and heroic mass of the High Renaissance and the exaggerations of Mannerism?

You can see this in the drawings related to the Medici Chapel tombs, in Florence’s Church of San Lorenzo. All those developments are there. Michelangelo drew on both sides of the page, so we are not mounting them in the standard way. They are installed so that viewers see both sides of each sheet and walk around to really sense his thinking and rethinking of ideas.