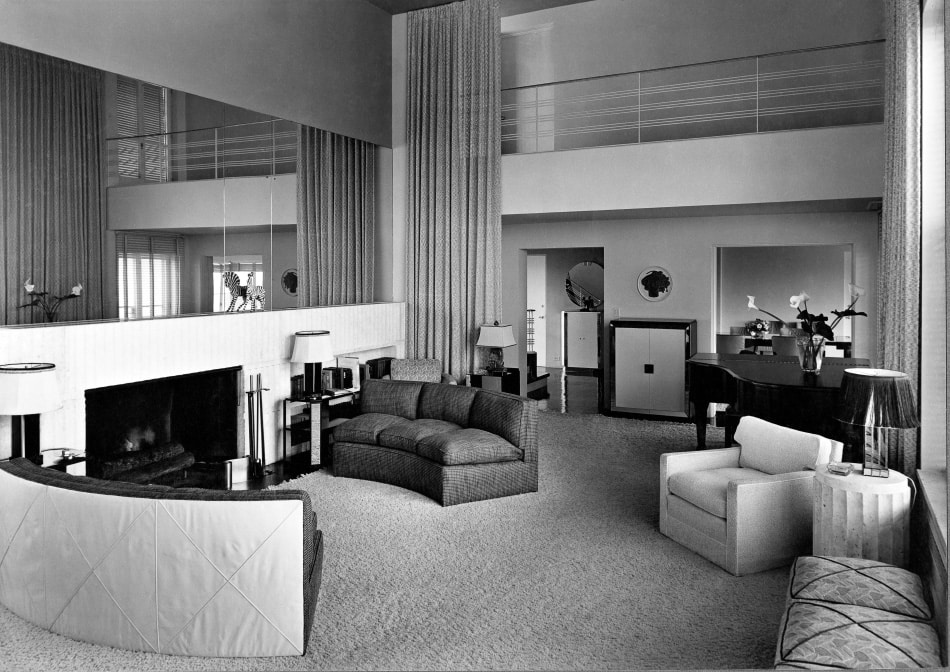

May 27, 2018In her latest book, Marilyn Friedman details how American taste definitively shifted to modernism, as evidenced in the home above, designed by George Fred Keck for Irma and Bertram J. Cahn, 1936 (photo by Hedrich-Blessing, courtesy of Chicago History Museum), and, top, the Los Angeles residence of celebrities Cedric Gibbons and Dolores del Rio, 1930 (photo by George Hurrell, Bison Archives).

In seven years of research for her new book, Making America Modern: Interior Design in the 1930s (Bauer and Dean), author Marilyn Friedman paged through virtually every shelter magazine published in that decade, including many long defunct, like Arts & Decoration and Good Furniture. “What interests me is how a style comes into being and evolves over time,” says the design historian, whose 2003 book, Selling Good Design: Promoting the Early Modern Interior (Rizzoli), about department store efforts to foster modern design in the late 1920s, was sort of a prologue to the current one.

In the more comprehensive Making America Modern, Friedman reveals that a taste for modern design, as opposed to the predilection for traditional interiors that had held sway for decades, remained limited in the 1930s to the sophisticated few, who never accounted for more than 10 percent of overall furniture sales. “Not everyone had the combination of money and confidence” to decorate his or her home in the sleek new style that was birthed at the Bauhaus and at the 1925 Paris Exposition des Arts Décoratifs and migrated to the United States in the years following. “Most people’s friends still had traditional homes,” Friedman says. “They would come in, look around and say, ‘What have you done?’ ”

The book marches year by year through the 1930s, with glimpses into the interiors of such residences as William Lescaze’s Bauhaus-inspired Manhattan studio for the Leopold Stokowskis and Hollywood film designer Cedric Gibbons’s glamorous home for himself and his movie-star wife Dolores del Rio. It also provides a look at the chic apartments and model homes by Eleanor Le Maire and Freda Diamond, among the unheralded female modernists whose reputations Friedman undertakes to revive.

Paul T. Frankl dressing table in the AUDAC exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York City, 1931, from The Art Digest, May 1, 1931.

Highlights include two seminal museum exhibitions — the 1931 AUDAC (American Union of Decorative Artists and Craftsman) show at the Brooklyn Museum of Art and the Philadelphia Museum of Art’s 1932 “Design for the Machine Age” — featuring rooms by design luminaries Donald Deskey, Paul Frankl, Kem Weber and Gilbert Rohde, whose work is avidly sought by collectors today. The book lands, more than 200 images later, at the “America at Home” exhibition at the 1940 New York World’s Fair, where industrial designer John Vassos’s curvilinear media room, dubbed the Musicorner, “epitomized all the strains that came together over the course of the decade.”

The first stabs at modern design in America had been “pretty derivative,” Friedman says, “with elements of Bauhaus and Art Deco brought by emigrés from Europe.” The list of such immigrant names is long, including Lescaze, from Switzerland; Weber, from Germany; Frankl, Joseph Urban and Frederick Kiesler, from Austria; and other designers and architects fleeing rising Nazism in Central Europe. Over time, U.S. designers like Minnesotan Deskey and New Yorker Rohde “melded European concepts with American ideas and materials to create what became American modern design,” Friedman says. “They looked at Europe but were not limited by it, bringing in streamlining and new materials like Vitrolite, a structural glass developed here.”

Whether foreign or native born, furniture designers working in the U.S. in the 1930s addressed what the American consumer wanted: curves and soft upholstery, Friedman says, “not the angular and functional look of the Bauhaus.” Common leitmotifs were oversize mirrors, rounded corners and long, low lines on both upholstered and case pieces, as well as the use of such materials as chrome and tubular steel. “The round mirrors came from Ruhlmann’s work,” Friedman says, referring to the high-end French designer Émile-Jacques Ruhlmann, whose studio’s work dominated the 1925 Paris expo. “The low profile I attribute to streamlining; it’s reminiscent of a train with a bullet end.”

American designers “looked at Europe but were not limited by it,” says Marilyn Friedman.

George Howe and Wharton Esherick living room in the Pennsylvania Hill House at the New York World’s Fair America at Home pavilion, New York City, 1940. Photo by Richard Garrison

The absence of ornament was another characteristic of the era. “Applied ornament is totally gone,” Friedman points out. “We didn’t have a tradition of handcraft as did Europe; we were a more machine-oriented society.” Instead, American designers innovated techniques like cross-graining, or juxtaposing different wood grains for decorative effect, as in Russel Wright’s 1934 model rooms for Bloomingdale’s.

Depression-era customers may not have flocked en masse to the new style, but it made for great press. A modern-design media juggernaut operated throughout the decade, fed by department store and museum exhibitions and by spectacular world’s fairs, including Chicago’s 1933 Century of Progress, the 1939 San Francisco Golden Gate International Exposition and the 1939–40 New York World’s Fair, all of which displayed the latest in domestic furnishings with as much hoopla as they did the marvels of air travel, television and other then-new technologies.

While the book offers abundant examples of the homes of the wealthy and powerful — including set designer Lee Simonson’s 1930 Park Avenue penthouse for CBS president William Paley and T.H. Robsjohn-Gibbings’s idiosyncratic 1937 apartment for Walter H. Annenberg on Philadelphia’s Rittenhouse Square — Friedman considers her primary focus a “narrower stream of practical modernism for the home.” Comfort, simplicity and practicality did indeed become the core principles of modern interior design in the 1930s, halted for a while by World War II before resuming with the mid-20th-century modernism that remains overwhelmingly popular today in both vintage and new iterations.

Here is the definitive scholarly chronicle of how it all happened.

Or Support Your Local Bookstore