April 17, 2017Manfredi Gioacchini captures both established and up-and-coming artists in their Los Angeles–area studios. Above, conceptual artist John Baldessari is pictured in his Venice, California, studio. Top: Painter and sculptor Billy Al Bengston, in his Venice space, takes in his work. All photos by Manfredi Gioacchini, from his book Portraits of Artists: Los Angeles (Utg)

During my first studio visit with John Baldessari, about a decade ago, when he still cooked up his ideas from a low-rent, rough-edged compound behind a surfboard shop in Santa Monica, he pointed out a chair beside a towering stack of books. With a simple metal frame and basic wood seat, it looked like a cheap desk chair designed before the age of ergonomics. It was, he explained, a leftover.

Baldessari had inherited the chair — and the Santa Monica studio — in the early 1970s from the artist William Wegman, his friend and compatriot in avant-garde goofiness, when Wegman quit the area for New York. It appeared as a prop in some of Wegman’s early videos and photographs, including a series called “Throwing Down Chairs.” Then it showed up in some of Baldessari’s photographs. A crack in the studio’s concrete floor also, Baldessari noted, appeared in the background of both artists’ photographic and video works.

The story of the chair stuck with me as an example of how even the most ordinary objects can acquire an extraordinary quality by virtue of being used by an artist (or two) who matters to us. If we are truly curious about an artist’s working process, we’re also curious about the nondescript seating in their photographs or the way they organize their paint tubes and brushes across a long table. (Some die-hard conceptual art fans might even care about that concrete crack.)

And in so far as a studio represents the most physical or visible expression of an artist’s working process, short of the finished artwork itself, the furnishings of the studio can often be read as the furniture of the artist’s mind — even in the case of Baldessari, who famously taught a beyond-painting course at CalArts called “post-studio.”

Pioneering California artist Ed Ruscha, whose work has been strongly influenced by the American West, was photographed in his Culver City studio.

Charles Arnoldi examines one of this paintings in his Venice studio.

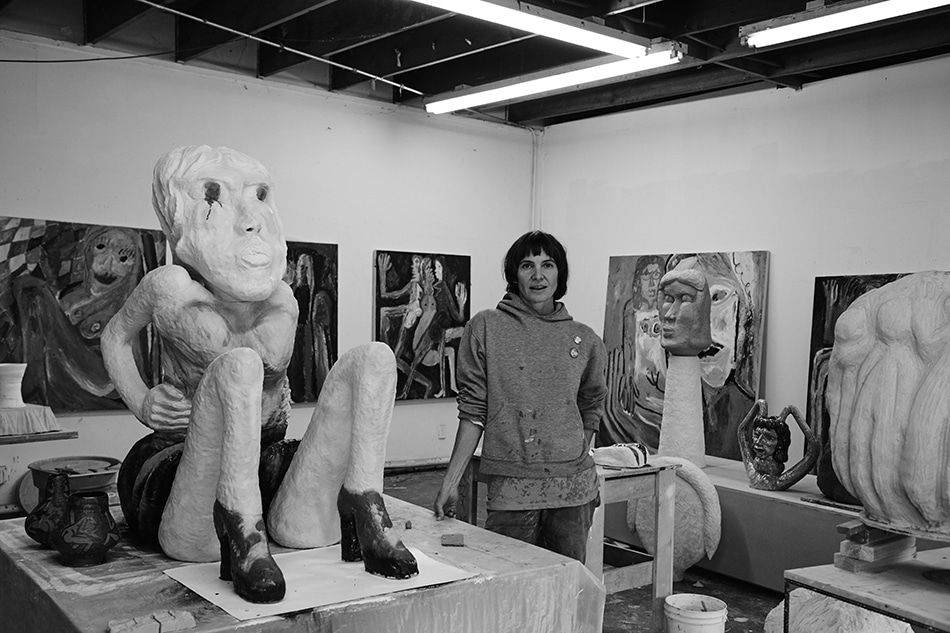

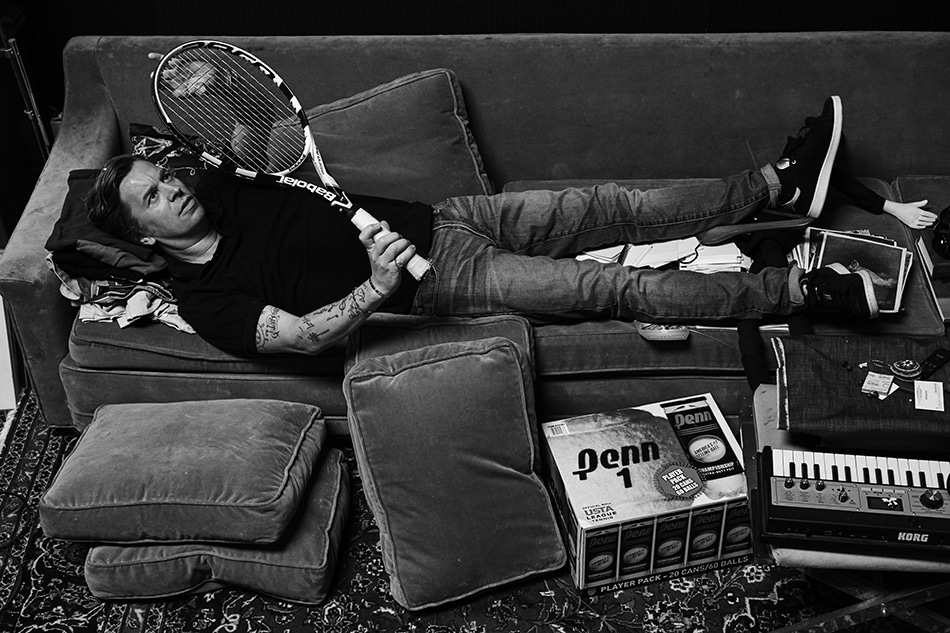

Those, at least, were my initial thoughts when paging through Portraits of Artists: Los Angeles (Utg), the new photography book by Manfredi Gioacchini featuring his black-and-white shots of more than two dozen L.A. artists. Some of his choices, like Billy Al Bengston, Ed Ruscha and Baldessari (shown here not in Santa Monica but in his new Venice space), are lions of the Southern California art scene. Others are still on the rise, like the transgressive sculptor-painter Ruby Neri (daughter of Bay Area legend Manuel Neri) and the of-the-moment history painter Friedrich Kunath.

In photographing these artists, the book also captures different types of studios in operation, from former industrial spaces that look ready for heavy machinery (see the portraits of Mark Bradford and Rebecca Morris) to more pristine gallery-like ones designed for displaying finished canvases to visiting curators (see Charles Arnoldi’s and Baldessari’s showrooms).

Some studios even seem to be designed specifically to enable the artists to contemplate or review their work. Take the case of Bengston, whom Gioacchini cleverly decides to shoot from behind, feet kicked up on a recliner, hand near his mouth as though he might be smoking. As the artist gazes at his works hanging on the wall in front of him, we as viewers are placed in the same contemplative position. A shot of the often-philosophical Italian transplant Piero Golia is similarly pensive, showing him leaning back in a chair and glancing just beyond his own reflection in a glossy table.

Then there are the spaces of the artists who have been described as having “eccentric inventor” streaks, like Tim Hawkinson and Richard Jackson. Both are hard-to-categorize sculptors who use unconventional materials, Hawkinson creating more intimate and bodily works, Jackson more macho and machine-powered ones, and their studios hold custom-made as well as recognizable tools.

If we are truly curious about an artist’s working process, we’re also curious about the nondescript seating in their photographs or the way they organize their paint tubes and brushes across a long table.

Installation artist Andrea Zittel designed Wagon Station, an experimental structure that she tested on her land in Joshua Tree, California.

One of the great insights of Gioacchini’s book is that the distinction between home and studio is not hard and fast. In several of the work spaces, you can see homey touches, like a teapot on a table in Chris Johanson’s studio, where a guitar leans against a wall as if it had just been used. And Kunath’s studio has so many domestic comforts, from Persian rugs and a burnt-orange suede sofa to a keyboard and drum set, that it is hard to tell whether this is a private space or a family room.

Of all the artists in the book, Andrea Zittel, who lives outside L.A. in the desert town of Joshua Tree, has arguably done the most through her own work to collapse the boundary between home and studio, or life and art. Along with offering her modular sculpture-architecture, like Cellular Compartment Units and Experimental Living Cabins, as gallery pieces, she has tested them out in her home or on her land. And, generally, she treats her home as a laboratory for figuring out how to live more authentically, economically and meaningfully.

When I visited her in Joshua Tree several years ago, she had redesigned or reconceived nearly every inch of every room, down to carving small craters into the wood surface of a kitchen table to serve as built-in bowls. Her goal there was to change the daily ritual of eating, so rote and mechanical for so many, into something more direct, so that she would become more aware of her own actions and more engaged in the activity. “For me, the best things never start as art. They just start for fun, or as an experiment,” she said. “You can always formalize them as art later on.”

As for Baldessari, when he finally moved into the larger, loft-like studio in Venice, he gave his old space in Santa Monica to his friend, former student and onetime studio manager, Analia Saban.

Known for a scrappy sort of resourcefulness as an artist (one of her first major works involved unthreading a canvas and rolling it into one big ball), Saban did not purge the studio of the previous occupants’ leftovers, not even Baldessari’s stacks of magazines. She kept the chair, too, repairing the seat with bright yellow duct tape. Then one day, Wegman visited the studio and was excited to see it again, prompting her to complete the cycle and return the old-new piece of furniture to him.

Purchase this book

or support your local bookstore