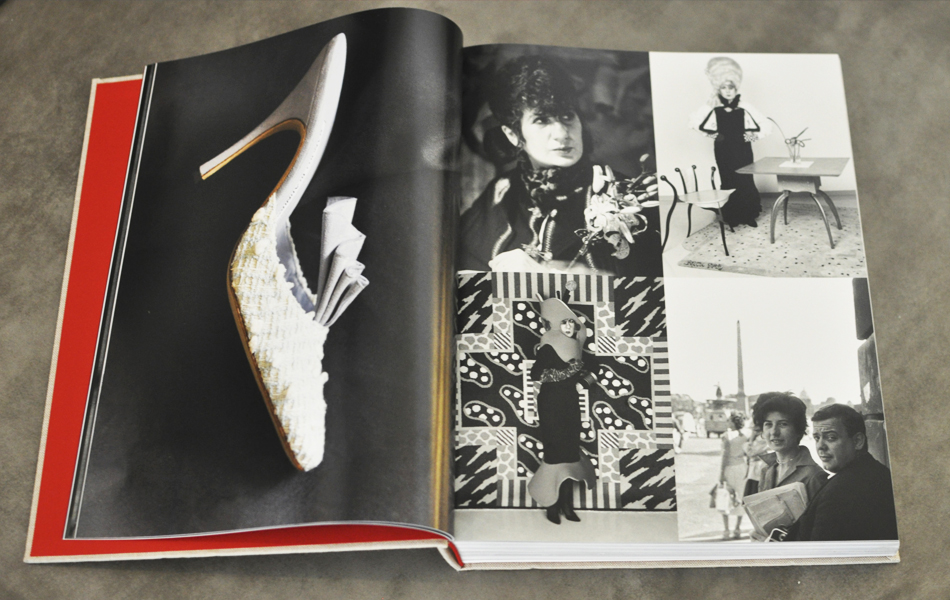

September 21, 2015Celebrity cobbler Manolo Blahník’s latest creation, Fleeting Gestures and Obsessions, offers a rare look at the influences and inspirations that keep him on his toes (portrait by Piers Calvert). Top: The two-tone lace-up Picasso bootie in suede, Fall/Winter 1976, made for fashion editor and icon Anna Piaggi. Photos by Michael Roberts unless noted

A fascinating look into the mind of a passionately creative person, Fleeting Gestures and Obsessions (Rizzoli) is a gorgeous new tome that chronicles the myriad inspirations of the sublime shoemaker Manolo Blahník. Over the course of what Blahník calls “a lifetime spent in pursuit of beauty,” the designer’s touchstones have spanned millennia and media, not to mention the breadth of the known world.

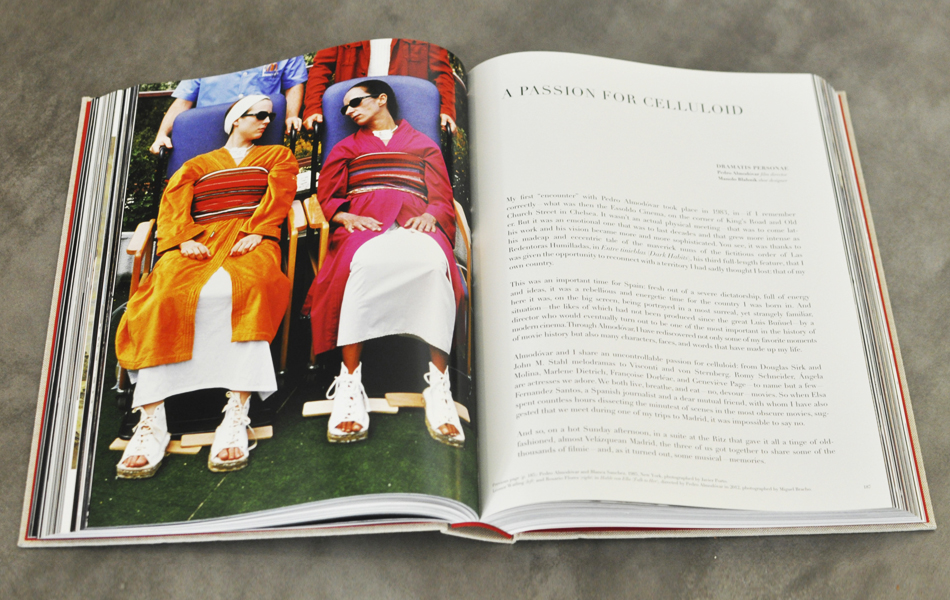

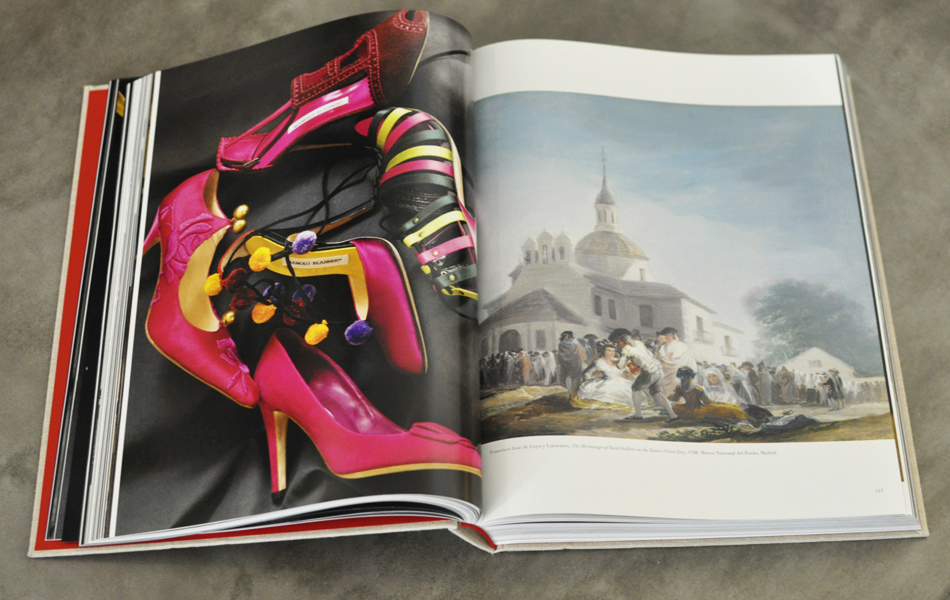

Profusely illustrated, Fleeting Gestures and Obsessions juxtaposes images of many of Blahník’s inspirations — great beauties and women of style, sculptures, paintings, buildings — with still-life studies of shoes from the Manolo Blahník archive, all captured by iconoclastic fashion director, photographer and illustrator Michael Roberts, who also wrote the book’s preface. As Roberts points out: “Here are shoes from an intellect that can find inspiration in the cinema of Luchino Visconti, Pedro Almodóvar, Sofia Coppola; the writings of Lampedusa, Gore Vidal, Tennessee Williams; the paintings of Mondrian, Zurbarán, Velázquez and Goya; the classicism of ancient Greece and Rome; the historical landmarks of Spain; the spatial concepts of twenty-first-century architecture.”

In the book, Blahník juxtaposes his lace-up Lola bottine — from the Spring/Summer 2003 collection and made of hand-knotted leather netting decorated with Spanish silk pom-poms and bordered in kid — with Goya’s Queen María Luisa on Horseback, 1799, whose palette the shoe echoes.

Connections, cross references and conversations fill the book: Vogue editor André Leon Talley and Blahník dissect the discerning eye of Diana Vreeland; filmmaker Coppola and Blahník share thoughts on Marie Antoinette over a meal at New York’s La Grenouille; architect Rafael Moneo and Blahník trade paeans to the form and function of each other’s work; auteur Pedro Almodóvar and Blahník talk movies in Madrid; and Prado deputy director Manuela Mena Marqués and Blahník stroll through the museum as they analyze color, light, texture, allegory and sartorial details, not to mention gossipy tidbits in the paintings. Opines Blahník in the Velásquez salon: “The horse is more chic than the woman riding it.”

Those who don’t know much about this legend of shoe design may find his personal history as fairy tale–like as his creations. Blahník, now 73, grew up on a banana plantation on La Palma, in the Canary Islands, where he was homeschooled. His mother, an early muse, was a highly stylish and determined woman who, frustrated by the limited selection of fashionable shoes available during World War II, learned to make her own from a local cobbler. Years later, when he was an aspiring fashion designer, Blahník had a chance meeting with celebrated fashion editor Vreeland, who looked at his book of fashion drawings and famously instructed him to “do extremities — you’ve got a gift for accessories and things.” The rest, of course, is history.

The book’s layout puts Blahník’s Locka evening shoe, from Autumn/Winter 2014 and made of Canepa silk with brocade and cotton fringe, in visual dialogue with the rich fabrics of Philip II’s bedroom in Spain’s El Escorial palace.

In Blahník’s work, colors zigzag and undulate, textures collide, tassels bobble, bands of suede or ribbon tie and untie and pom-poms do what they are supposed to do: astonish. The effect he is aiming for is possibly revealed in a certain anecdote in the book, in which Blahník describes the moment when a fashion collection hit him like a thunderbolt: “In 1967, In Geneva, I am astounded by the beauty of M. Saint Laurent’s Bambara collection. Pure genius. Modern. Opulent. Sexy. A shock and a feast. Bold. Daring.” The same enfilade of words applies to any of the shoes pictured in this volume.

Recollections scattered through the book suggest an exceedingly charmed life: Blahník dancing with French film star (and Catherine Deneuve’s sister) Francoise Dorléac at Chez Castel in Paris; wearing Cecil Beaton’s hat to Hamish Bowles’s 50th birthday party; donning a Dior New Look coat in red flannel with velvet that caught the editorial eye of Anna Piaggi; dodging traffic to cross a road and ask Eric Boman about the plastic schoolboy satchel he was carrying; running into Penelope Tree in the Los Angeles airport and the two becoming fast friends. And if all that isn’t cinematic enough for you, there’s Blahník’s appearance in an actual film: Nicholas Roeg’s Performance, of 1970, in which the designer dances with Janet Street-Porter.

For Autumn/Winter 1998, Blahník did his Lapis mule in golden-hued Imperiali satin, here set off by a printed-chiffon tie by Gandini.

Chapters are devoted to a dazzling variety of subjects, from Lampedusa’s novel The Leopard, and its Visconti film version, to a day spent at Spain’s magnificent royal palace El Escorial. In a section devoted to the allure of the ancient Hellenic and Roman worlds, Blahník notes: “It is practically impossible not to be a fervent admirer of Professor Mary Beard. I have been crazy about her work since I read The Parthenon.” In his conversation with the noted classical scholar, which appears in the book, the two discuss such historic shoe styles as the ciabattina, Persian slippers and the amazing hinged Tyrrhenian sandal.

It has long been observed that the ancient Greeks had more than one word for love, up to four or five for its most important forms. It will hardly come as a surprise to Manolo aficionados that they also had more than 80 words to describe shoes.

Shop Manolo Blahnik on 1stdibs

Purchase This Book

or support your local book store