March 1, 2020Marcel Wanders believes that design should be playful, romantic and verging on surreal. At last year’s Salone del Mobile, he introduced his Nightbloom lighting collection for Lladró, seen here. Top: Wanders created the Diamond armchair and sofa as part of Louis Vuitton‘s Objets Nomades collection, presented at the 2019 Fuorisalone in Milan. Photo courtesy of Louis Vuitton. All other photos courtesy of Marcel Wanders unless otherwise noted.

“I have a quote written down somewhere,” says the Dutch product and interior designer Marcel Wanders, “that goes something like, ‘If painting is about love, and theater is about love, and dance is about love, and music is about love, why do we think design is about functionality?’ ”

A towering man with piercing blue eyes and white-gray hair, Wanders has joined me in the conference room of the Amsterdam canal house on the banks of the Amstel River that serves as his headquarters and studio.

The wall to our left is decorated with Menagerie of Extinct Animals wallpaper, a pattern created by the furniture brand he cofounded, Moooi, with the wallcovering company Arte. We sit on two of his gray felt VIP chairs, designed for the Royal Wing Room of the Dutch pavilion at the 2000 World’s Expo in Hanover, which glide across the floor, and under white porcelain lamps that look like billowy flower petals, part of his recent Nightbloom lighting collection for the Spanish ceramics company Lladró.

Wanders’s whimsical interiors for the Mondrian Doha in Qatar include the tea room, with its cartoon-like white trees.

“Functionality is the minimum requirement of design, not the ultimate requirement,” he continues. “I think our most beautiful side is not our brain. We are smart, but we are not rational beings. We are very strange, magic wonders, incongruent, irrational beings. It makes us painful and annoying at times, but it’s who we are. And that’s what design is about.”

Wanders’s Skygarden light for FLOS hangs above his Knotted chair for Cappellini.

Wanders, who launched his design career in 1994 as cofounder, with Renny Ramakers and Gijs Bakker, of Droog, has since built an international brand of his own, Marcel Wanders, embodying his sense that design should be playful, romantic, verging on surreal and — when there’s a choice between the two — over- rather than understated. His style might best be defined as contemporary rococo.

Individual pieces that have reached design icon status include his breakthrough Knotted chair (1995–96), made of aramid-fiber cord; his Skygarden pendant lamp for FLOS (2007); his monumental Calvin floor lamp (also 2007). Then there’s the Happy Hour Chandelier (2005), created by Wanders with choreographer Nanine Linning, which is part a design object, part a performance in which a “dancing angel” hangs from the center of the fixture, serving little spoons of chocolate mousse and champagne flutes to the people below.

At the Andaz Amsterdam Prinsengracht, Wanders referenced Dutch history and iconography in spaces like the Delft Blue room.

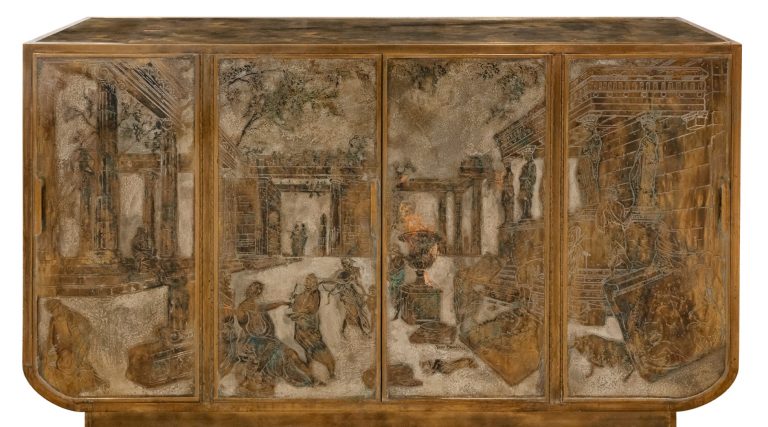

His recent studio collaborations include creating bespoke hides with leather artisans from Bill Amberg Studio and designing crystal game boards for Maison Baccarat, in addition to the handcrafted Nightbloom lamps for Lladró.

For the last project, Wanders and his team drafted several different styles to present to the Valencia-based company. “I hoped they would choose the Nightbloom design, but I wasn’t certain they would, because it’s a complex piece,” he says. “I thought it was a bit challenging, because they’re a company that does ceramics, figurines, not lamps. But in the end, they were able to do it, and I was super excited about it. It’s a piece that I think is an absolute icon. It has a tactility that is unprecedented, it has depth, it has eternity in itself.”

Marcel Wanders and his creative director, Gabriele Chiave (right), who has been with the design firm for 13 years. “Gabriele has worked his way up in the company and now stands next to me,” Wanders says.

“These are the types of things that are the antiques of the future,” he adds. “And that’s how I want to look at my work — as things that I make to be sold in fifty to sixty years.”

In addition to creating the antiques of the future, Wanders is known for designing what might be called experiential spaces — interiors imbued with his design ethos, as in the eclectic and theatrical Mondrian South Beach hotel, in Miami (2008), and the Andaz Amsterdam Prinsengracht hotel (2012).

The Mondrian South Beach was conceived as “Sleeping Beauty’s castle,” with a pool area comprising dramatic arched cabanas and curtained “seating islands.”

Now 56, Wanders says he’s in the process of “reshuffling of moods, priorities.” Currently, his studio employs about 50 people at any one time, working to realize Wanders’s visionary ideas. Although still very much in charge, he has found a true colleague in his creative director, Gabriele Chiave, who started with the company 13 years ago. “Gabriele has worked his way up in the company and now stands next to me,” Wanders explains.

Wanders collaborated with leather craftsmen from Bill Amberg Studio on a collection of bespoke hides, which are digitally printed with computer-generated fractal patterns. Photo by David Cleveland

“I think in the next five years, something is going to change, that’s what I feel,” he says when asked about the future. “It’s probably the right time. There are a lot of things I’ve proved and that I don’t have to prove again. There are new areas in which I’m needed.”

Looking back on the work he’s done over the past 25 years, or Googling himself, Wanders sees “some things out there that look like me but not completely me. There’s a whole other side of me,” he says, adding that he’d like to try to “be more complete or honest as an artist.” To do so, he feels it’s necessary to make work that has more limited editions, that can be considered his personal work.

By way of example, he shows me photographs of the 2009 light installation Wallflower Bouquet, which was exhibited at his 2015 retrospective at the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam. It comprises a circle of floral-shaped LED lights whose colors change continually based on a library of photographs of wilting and dead flowers.

“I think exploring death is the ultimate creative goal in art, and probably in design, probably in all the arts,” he says. “I mean, nobody wants to die, and all of us try to find a way to leave a mark and to go beyond death. Artists especially have that need, so we try to make things that will be more important than us. It’s an attempt to make life out of death.”