November 10, 2024As a designing duo, father and son Philip and Kelvin LaVerne were devoted to their craft. During the early years of their collaboration, in the 1960s, Kelvin kept an apartment above their workshop, on Manhattan’s East 28th Street, and would often work late into the night. Philip, meanwhile, continued creating right up to his death, in 1987.

The day before he died, although confined to a hospice bed and barely able to speak, he handed Kelvin the drawing of an abstract sculpture on a scrap of paper. The sketch would be transformed into a coffee table called Triumphant, consisting of a glass top on a patinated-bronze base shaped like a coil set on its side.

Famed for their beautifully intricate and original furniture made from metal, the LaVernes worked together for almost four decades. From 1960 to the early 1980s, they had a successful three-story gallery at 46 East 57th Street, which attracted a stellar clientele that included Frank Sinatra; the writer Dale Carnegie and his wife, Dorothy; and New York mayor Abe Beame. In the mid-1960s, Jackie O. commissioned a dining table for the Onassis yacht with a motif inspired by Greek ruins.

From the turn of the 21st century on, a number of New York dealers have steadfastly championed the LaVernes’ creations. Paul Donzella acquired his first piece — a circular bronze coffee table shaped like the stump of a tree — in 2005. “It had this deep abstract relief all around it, which really looked like bark,” he recalls. “It blew me away.” Ever since, he has been selling LaVerne pieces to top interior designers, like Thad Hayes, Robert Stilin and Steven Gambrel.

In 2008, Cristina Grajales held an exhibition titled “The Poetry of the Soul, Works by Philip and Kelvin LaVerne” in her then gallery space on Soho’s Greene Street. “When I discovered their work, I found it so poetic,” she says. “It’s almost as if they took paintings off walls and transformed them into functional objects.”

She still remembers when art patron Maja Hoffmann — best known for her Frank Gehry–designed LUMA foundation in Arles, France — acquired a console from the LaVernes’ Metamorphosis series: “It took exactly two seconds to sell that piece.”

Evan Lobel started dealing in LaVerne pieces shortly after opening his gallery, Lobel Modern, in 1998. A decade ago, he was approached by Kelvin about collaborating on a book — a lengthy process interrupted twice by the then 77-year-old designer’s bouts of ill health.

Finally released last month, the resulting volume, Alchemy, from Pointed Leaf Press, is not only wonderfully documented but also provides new insight into the breadth of the LaVernes’ output. In addition to chapters on the more familiar furnishings, there are sections devoted to the cast-bronze sculptures they created in the 1970s and Kelvin’s paintings, largely done on bronze and pewter.

It is the furniture — or “functional sculptures,” as the LaVernes liked to call them — that really sing, however. The pieces range from the highly decorative and detailed to more abstract and textural.

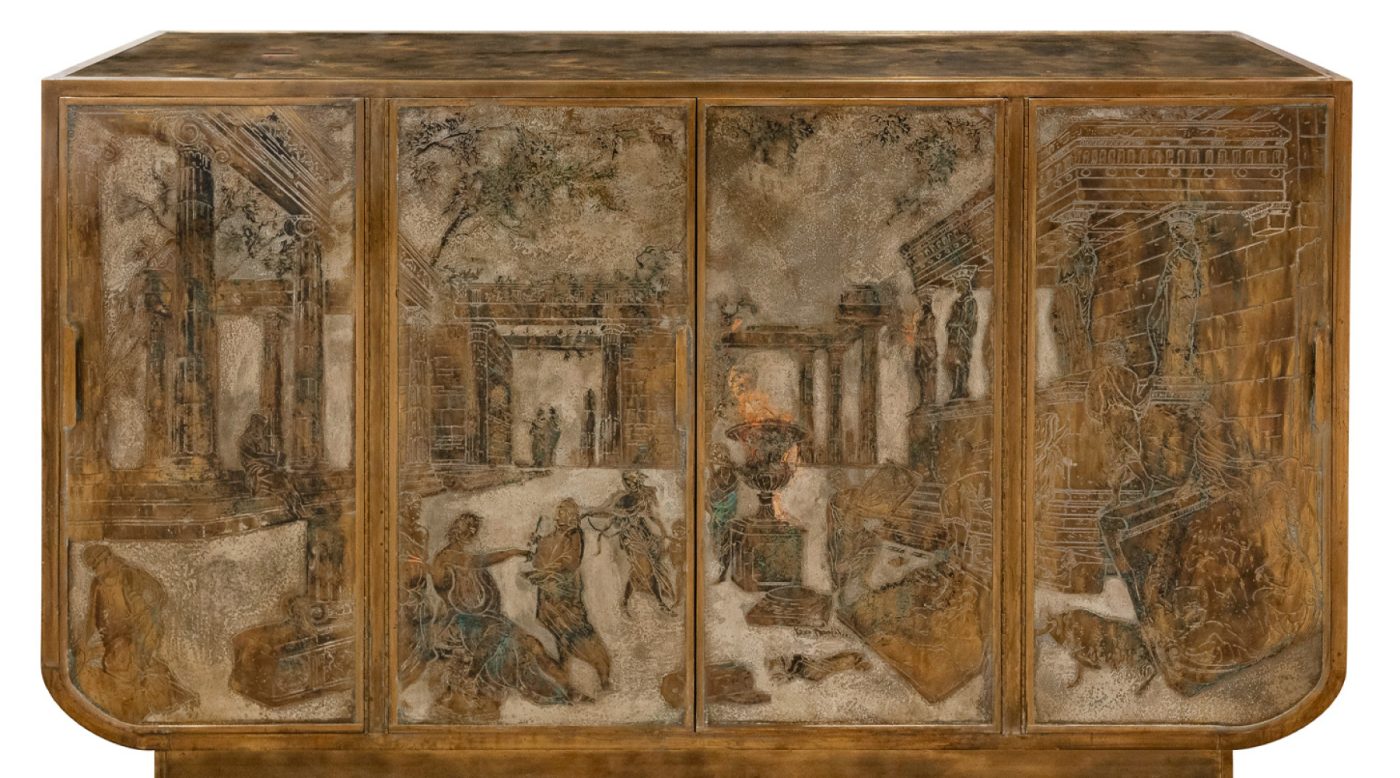

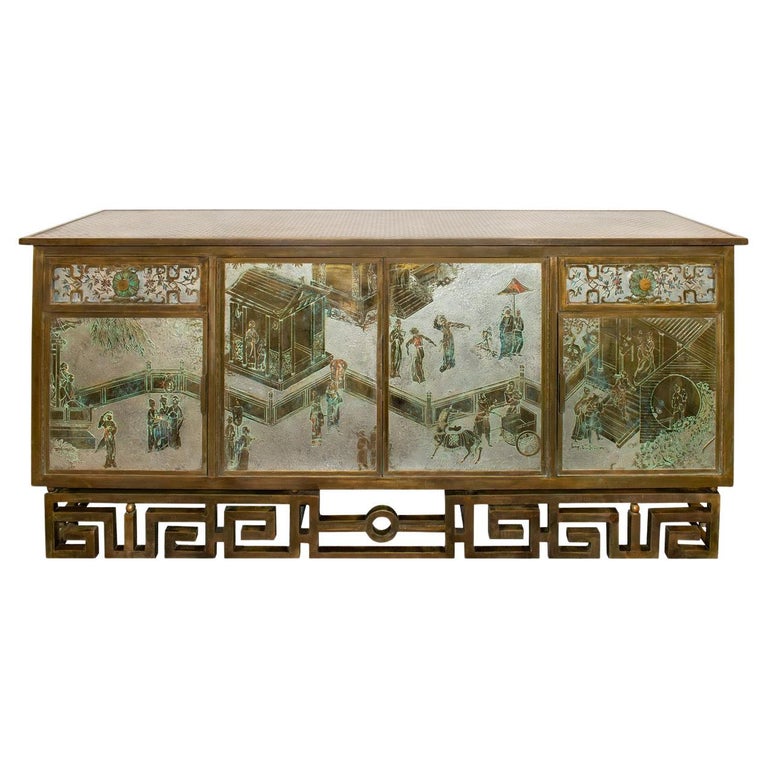

In the former category is their Historical Civilization series, consisting mostly of metal tables and chests whose surfaces are elaborately engraved and painted with motifs inspired by ancient cultures. Kelvin was drawn to European antiquity, Philip to Asian.

The Pharaoh table sports a base in the form of a tapered pyramid and embellishment made up of hieroglyphs and other Egyptian-style figures. The starting point for the Odyssey table was a group of sketches Kelvin made of the Erechtheion ruins in Athens, while the Chan series is based on a landscape painting dating to the 6th-century Chinese dynasty of that name, depicting ducks on a pond, trees, a gate and a wall.

Inspiration for other works came from diverse sources. The motif on the Eternal Forest coffee table comprises rows of trees in green, patinated bronze tones, while the Bathers collection brings together a group of lithe figures on a beach. Dating from the early 1970s, the Symphony table has a base whose form was inspired by a line drawn by Beethoven on the manuscript of his third symphony.

The LaVernes’ more abstract creations mostly date to the 1970s onward. Examples include the Metamorphosis series, which consists of irregularly shaped patinated-bronze tables with holes cut out of them, and the Moment of Truth table, composed of a glass top on a rough bronze base that looks vaguely like a Cubist reclining figure.

Philip was born in 1907 in New Jersey. His father, Max, was a muralist, whom he started assisting when he was just 12. After Max left the family and moved to the West Coast, Philip did odd jobs for a bit before becoming an army photographer during World War II.

At the end of the conflict, he set up a firm called Gem Stone Arts, designing and making furniture and room decor predominantly from smoked mirrors. For a few years, he also fabricated wood cabinets to house black-and-white television sets. When he decided to take his career in another, more artistic direction, it was his experimentation with those other materials that led him to the metalwork with which he made his name.

Born in 1937, Kelvin studied art history at the City College of New York and, after transferring, at Parsons School of Design, while also attending the Art Students League. After graduating from Parsons, he went to work with his father full-time. ” (Another son, Seymour, oversaw sales at the LaVerne gallery until his untimely death, in 1967.)

From the start, Philip and Kelvin seem to have been incredibly in sync, and perfectly complementary. “They would constantly make suggestions to each other on how to make a design better,” says Lobel.

Philip was responsible for the forms, Kelvin for the decoration. The former were often intriguing and sometimes highly complex. The Chi Liang coffee table, for example, has an undulating shape meant to represent “the uncertainties or vagaries of life,” Kelvin once wrote. The diversity of leg forms for different tables is particularly impressive, as is the appetite for experimentation that led to this diversity.

“They weren’t just guys making pretty things,” says Lobel. “They were chemists and physicists, and they had a deep thirst for trying to figure things out. They never stood still.”

The LaVernes did a great deal of research to figure out how to achieve the perfect patina that would give their creations the appearance of antiques. They tried out different soils and metals, working principally in bronze and pewter. After being buried for months at near freezing temperatures in soil, their creations would darken and acquire a mottled effect.

The pair also explored different manufacturing techniques. They used torch brazing, in which a filter alloy acts as a bond between two pieces of metal. And, in the early ’70s, the made both furniture and sculptures from cast bronze. The process, however, did not prove financially viable.

“They sometimes would have to cast something ten times before they got it right,” explains Lobel. “It cost too much to get a perfect result.”

The finesse of both their decorations and fretwork is quite astounding. “There was nothing casual about their designs,” says Lobel. “Everything was highly thought out.” Most pieces were either one-offs or produced in limited editions. They felt the importance of the ideas behind them would be diluted with higher production numbers.

After Philip’s death, Kelvin completed their outstanding orders and then stopped making design pieces altogether, choosing to create abstract sculptures instead, which he did into the 1990s.

The Lavernes, Lobel concludes, “had an eye on their legacy. They put a lot of time and effort into doing something unique. I think they’re going to be viewed among the most important artist-designers of the twentieth century.” No doubt, Alchemy will cement that status.