Maya Lin has recently published a new monograph, Topologies, chronicling her entire career (photo by Walter Smith). Top: Lin designed the Ellen S. Clark Hope Plaza, which opened in 2010 at the Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri. Photos, unless otherwise noted, courtesy of Rizzoli

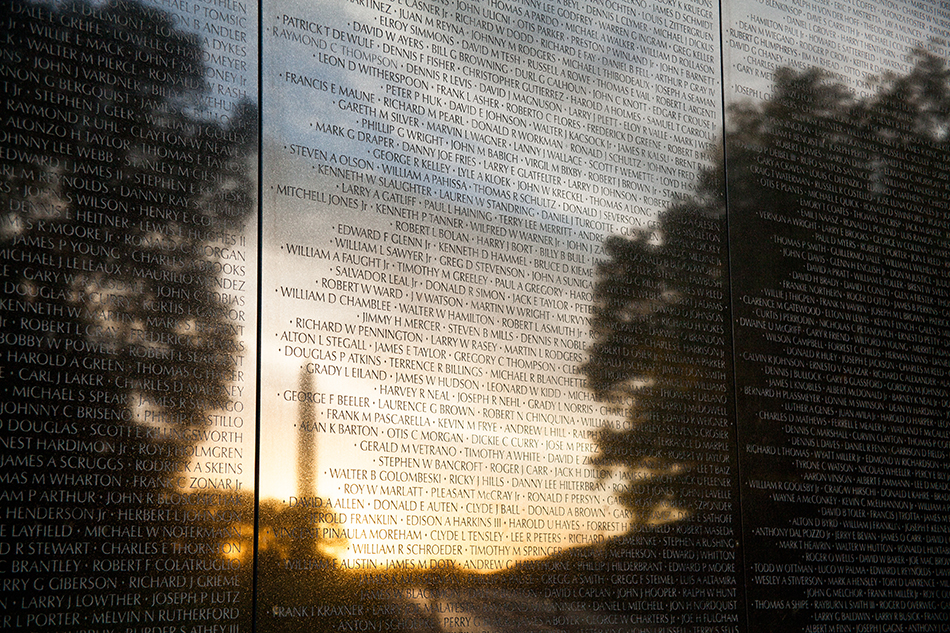

October 26, 2015Maya Lin deserves a victory lap. It has been more than 30 years since Lin, then a Yale undergraduate, won the competition to design the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington. That early success made her famous, but not always in ways she liked. “Every time there was a bombing or a plane crash, I would get a fax,” she told me in 1999. Hoping to be known as more than “a person whose work concerns death and destruction,” she accepted few further memorial commissions, instead pursuing what she saw as two different careers. “I want to be taken seriously as an artist, and I want to be taken seriously as an architect,” she said at the time, “and so I consciously keep them as separate fields.”

But that was then. Having achieved success as an artist, whose best work abstracts forms drawn from nature, and as the designer of buildings with sculptural aspirations (as well as the creator of several more memorials), she is beginning to embrace the connections among her diverse bodies of work. As she writes in Topologies (Rizzoli), “Each discipline influences and informs the others.” In fact, Lin is now more interested in connections than in Boundaries (the title of her last big monograph, in 2000). Hence her new book, over the course of 400 pages, chronicles her entire career, starting with the veterans memorial (her handwritten competition entry is reproduced in full), then moving on to less familiar projects. One of the best reasons to buy Topologies is to see Lin’s architecture, including several private homes that can be visited only in photos and two somewhat more public buildings for a Children’s Defense Fund camp in a remote part of Tennessee. (The good news for fans is that a very visible Lin building, the Novartis Institute for Biomedical Research, will open this fall in Cambridge, Massachusetts.)

True, much of Lin’s art is public and hard to miss: Wavefield, which renders the surface of the ocean as an earthwork, covers 11 acres at Storm King Art Center, in upstate New York. The Meeting Room, a memorial to Doris Duke, who spearheaded preservation efforts in Newport, Rhode Island, re-creates in a Newport park the foundations of historic buildings.

Lin’s interactive project “What Is Missing?” explores how lives have been diminished by environmental degradation.

But her more delicate work, seen at occasional gallery exhibitions (and collected by the likes of Michael Bloomberg and Barnes & Noble founder Leonard Riggio), can be particularly compelling. In one series of pieces, she re-creates rivers — including the Yangtze and the Hudson — using thousands of ordinary metal pins inserted directly into walls. From a distance, the pieces read as silvery pencil drawings; up close, they claim territory as confidently as the work of Richard Serra and Walter De Maria.

Now Lin is devoting much of her time to an especially poignant project. “What Is Missing?” is an account, in a range of media, of how lives have been diminished by environmental degradation; one focus is the loss of species; another, the loss of habitat. A video titled Unchopping a Tree puts rainforest destruction in chilling context: At the current rate of deforestation, New York’s Central Park would last nine minutes; London’s Hyde Park only four. Much of of the piece exists in cyberspace. Visitors to whatismissing.net are invited to describe things — plants, animals, sounds, smells, views — that have disappeared during their lives. A large chunk of Topologies is devoted to the project, which Lin describes as her “final memorial.”

The book has a foreword by the author John McPhee, who has had his Princeton journalism students write about Lin. It also contains celebratory essays by the New Museum director Lisa Phillips, who calls Lin’s work “both literal essence and poetic allusion,” and the architecture critic Paul Goldberger, who focuses on Lin’s restraint. (His essay is called “The Courage to Omit.”) But the most surprising aspect of the book is that the text describing the projects is written by Lin herself, in the first person. The words aren’t especially elegant, but they don’t need to be; they describe, in the plain language of Lin’s native Midwest (she’s from Athens, Ohio), projects that have the power to astonish, inspire and provoke — and, possibly, help save the planet. When the ideas are as strong as Lin’s, they don’t require much elaboration.

Purchase This Book

or support your local bookstore